STEVE LIEBER JOINS TOUCAN!

Dilettante 001: Why I Love Comics

It was 1978, I was 11 years old, and I had a growing sense that my time was not my own. I was already a comics fanatic, lured in by nifty pictures and cliffhanger endings and a thrilling sense that some of the stories were part of a bigger story, but I could feel my father’s disapproval of this obsession. Maybe that made them all the more attractive.

I had recently read a few things that mentioned a comics publisher called “EC.” Years ago they were supposed to have put out the coolest, scariest, most dangerous comics ever made. I had to learn more. While my local library only had two or three listings under “comic books, strips, etc.” the main branch had dozens including one that promised all the answers. But it wasn’t easy to see. It was part of their noncirculating collection.

My father wouldn’t be happy that I was wasting an afternoon reading about comic books.

I had to wait for a free weekend, walk 15 minutes to a bus stop, wait half an hour for an unfamiliar bus, ride to the library, navigate the enormous card catalog, climb three long flights of marble steps, request a request form, fill out a request form, submit a request form, walk down cavernous hallways the length of a football field, and wait again in a room full of books behind glass for an elderly man to bring the book to me down that long hallway on a squeaky, trundling cart.

Agent, Inc.

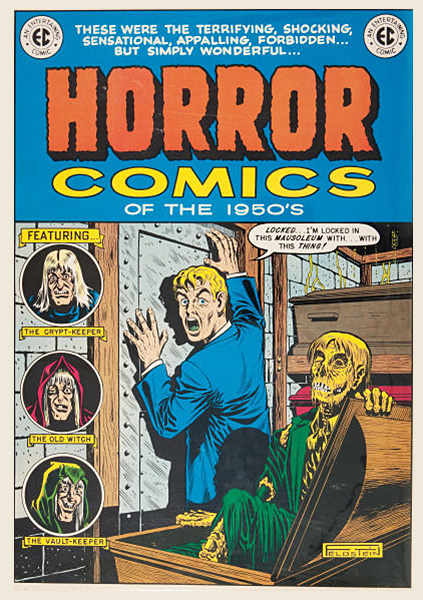

The book was called Horror Comics of the 1950s. It was a hardback, enormous and heavy. Anyone reading this knows what was in it: a glorious collection of EC’s horror, science fiction, and suspense stories. It felt like I’d been waiting my entire life to get my hands on it. Certainly the hours I’d waited that day felt like months. Now that I had it until I had to go home, the afternoon flew by in a matter of minutes.

The stories were landmines: blowing any sense of comics’ comfort or familiarity to pieces. The one thing I took for granted in comics was that at the end of a story, everything went back to normal. Not with these stories. Every eight pages a life was ruined, a plan foiled, a hierarchy upended. Things happened to these characters, and nothing would ever be the same for them. I knew these stories were from a long time ago—no one wore hats like that anymore—but they felt alarmingly fresh and disturbing. And towards the end of the book, there was a story that changed everything for me: “Master Race” by B. Krigstein. (Editor’s note: Google “Master Race Krigstein” for examples of this work.)

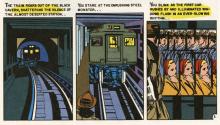

I’d read thousands of pages of comics, but I’d never seen anything like this. The story was dark, with a narrative that moved from the present to Holocaust-era Germany, and back to the present. It was written in the second person and forced the reader to identify with a protagonist who can only be described as “the bad guy.”

And the story was told with visual techniques that were entirely new to me. At the end of the first page (at right), the artist used repeated identical images superimposed in a single panel to communicate a subway train speeding into a station. The first panel on the second page showed fewer of these strobing images, and made it clear the train was slowing down.

These static drawings were showing differences in speed and in time passing.

Later in the story, a character was shown in four thin panels. all shot from the same angle, flailing as he loses his balance and falls onto the subway track with another train approaching. Then the panels cut back and forth between him and the train, slowing down time, delaying the inevitable until . . .

BRAAAAAAAT, another strobing image panel like the one at the start, indicating that the train was blasting through without stopping. There was no sound effect, but I “heard” the train clearly and understood the violence implicit in its movement.

My brain recognized what was happening in these pictures. The comic had created slow motion with a succession of still drawings, then sped the action back up with another.

I had always read comics for the story being told, but here I was fascinated by how the story was told.

I read it again and again, long past the time I should’ve closed the book and caught the bus home, knowing I’d get in trouble for coming home late. But it was worth it—I’d learned that a person making comics could make choices that control the passage of time. And maybe that person could be me.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante column appears the second Tuesday of each month on Toucan. Why Dilettante as a title for this column? Steve remembers a remark the legendary Will Eisner once made that had influenced Lieber as an artist: Comics is a dilettante’s medium. A cartoonist needs to know a little about writing, a little about drawing, a little about typography, acting, costuming, color, etc. Mastery of comics requires dilettantism in a dozen other disciplines.