MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 055: It’s Pronounced ZEEN

Maggie’s World for September mentioned that comics “Stuff” includes fanzines. It might be a good time to provide more information on those amateur self-publishing projects. Their form of social media isn’t often discussed these days. (They’re so much out of casual conversation that I’ve heard people pronounce one as a “fanzyne.”)

Raymond A. Palmer

I have long contended that he was the second-most-important science fiction editor. But it wasn’t until recently that I learned that Ray Palmer (August 1, 1910–August 15, 1977) also helped to create the very first fanzine. In fact, that term wasn’t invented until more than a decade after he’d done it.

In the early days of the development of science-fiction magazines, most of their enthusiasts knew each other only by way of correspondence. Hugo Gernsback’s magazines Science and Invention (1920–1931) and Amazing Stories (1926–2012, with existence as a newsstand entity now apparently gone) were introduced on newsstands nationwide. Among departments in his magazines was a letters column in which participants were identified by the sender’s full name and address. A couple of readers soon proposed a club-by-mail. Quoting from Fred Nadis’ biography The Man from Mars: Ray Palmer’s Amazing Pulp Journey: “One result [of creation of their Science Correspondence Club] was the first ever ‘fanzine’ in existence, which [Walter L.] Dennis and Palmer coedited and named The Comet. Its first issue was released in May 1930 and consisted of 10 mimeographed pages.”

I haven’t been able to find out much about Dennis; The Gernsback Days (2004) by Mike Ashley and Robert A.W Lowndes gives his birth year as both 1911 and 1913. He seems to have left the field before 1940, and Fancyclopedia 3 gives his dates as 1911–2003. But his co-creator, who suffered from a spinal defect that left Palmer (as he wrote) a crippled hunchback, parlayed his place in the field into editorship of Amazing Stories.

A footnote: The Silver Age version of The Atom—first appearing in DC’s Showcase #34 [September-October 1961]—was named “Ray Palmer” by science-fiction professionals DC Editor Julius Schwartz and writer Gardner Fox.

How’d They Do It?

Getting back to the early days of fanzines: Many of the early self-publishers were basically young adults with a yen to communicate with other young adults of similar interests, no matter where they lived.

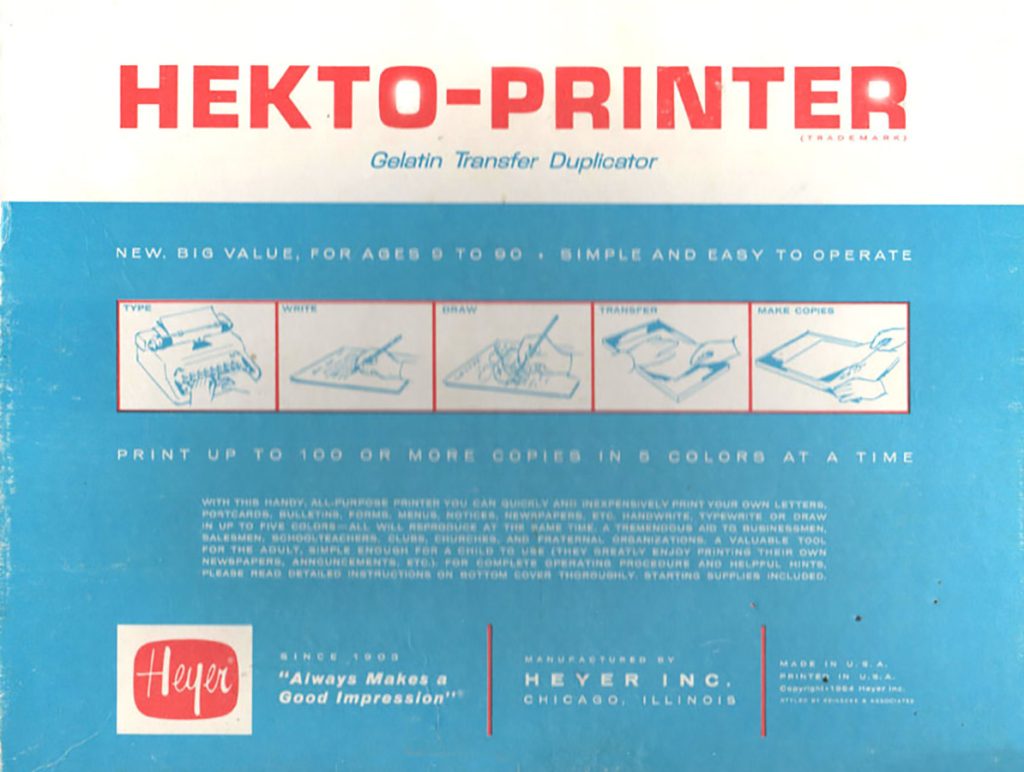

If those other buddies were few, the “magazines” could be produced using carbon paper for duplication. But that only worked for about a dozen correspondents. As friendships grew, some publishers (such as eventual Vampirella creator Forry Ackerman in his early days in fandom) moved on to the longer print runs enabled by hectograph. The hectograph was a messy form of spirit duplication, and the default for most long-time fantasy and science fiction self-publishers became the mimeograph.

Then …

According to the science-fiction reference site Fancyclopedia.org, (based on Jack Speer’s Fancyclopedia and Dick Eney’s Fancyclopedia II), Louis Russell Chauvenet (February 12, 1920–June 24, 2003) coined the term “fanzine” in his Detours fanzine (October 1940), announcing “our intention to plug ‘fanzine’ as the best short form of ‘fan magazine.’ ”

And that became the standard term.

The online Fancyclopedia resource provides many details. It kicks off its information with the definition of “fanzine,” “A magazine published on a nonprofessional basis by a fan for the amusement of other fen. … The term is a contraction of fan magazine and sometimes abbreviated as fmz. The more common short form is zine.”

It Was Comics Time

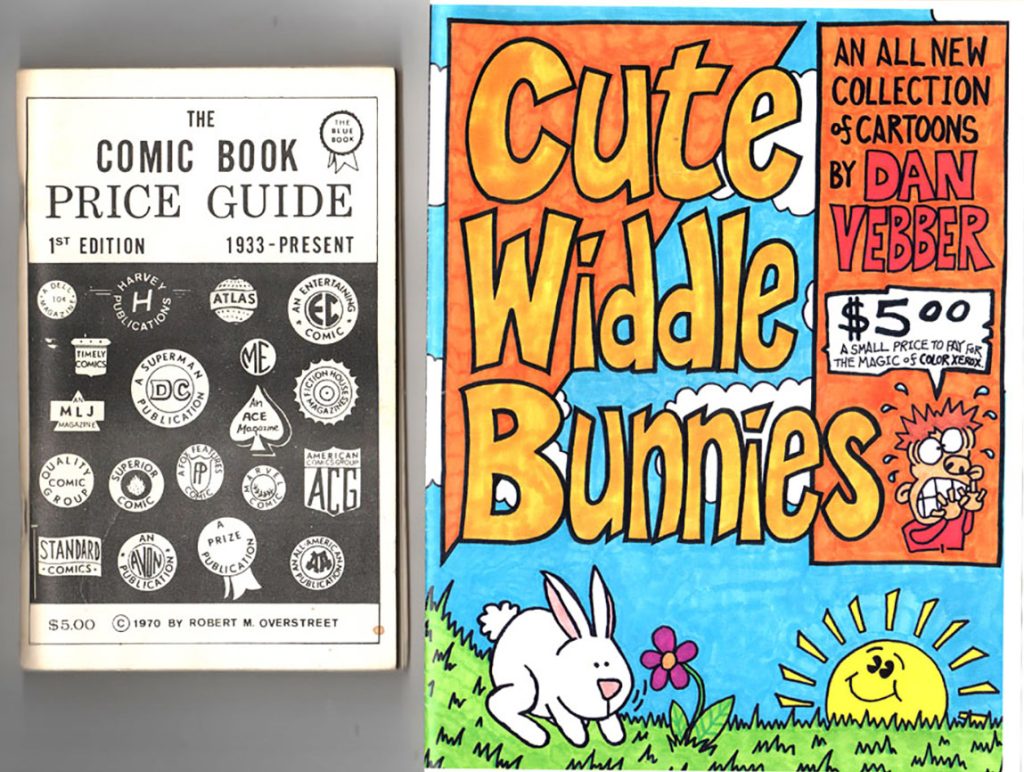

Several self-published projects in early days were devoted to a specific type of comic art. Thanks to its science fictional nature, for example, Flash Gordon inspired science fiction fan David Kyle to publish what may have been the first “comics fanzine”—Fantasy World, devoted to comic strips—in 1936. In the 1950s, some soon-to-be-pros devoted their amateur presses to E.C.’s comic books, and others published what might best be described as “satire fanzines.”

And then came the 1960s.

Dick and Pat Lupoff came to the 1960 World Science Fiction Convention, where they distributed copies of their mimeographed Xero, including the first installment of the nostalgia series All in Color for a Dime. They attended the costume event as Captain and Mary Marvel. Given those inspirations, my husband-to-be and I decided we wanted to know more about the largely anonymous world of comics creators.

Almost simultaneously, Roy Thomas and Jerry Bails produced the first issue of Alter-Ego (with a focus on superhero comic books). And Don and I produced the first issue of Comic Art (with a more general look at the range of comic art—from comic books and strips to magazine cartoons to animation). It was spring of 1961, it was comics time, and many other comics buffs decided to join in the fanzine fun.

Variety

Some self-publishers wanted to tell their own stories via their own writing and art.

Some wanted to begin the laborious project of providing a history of comics.

Some wanted to share details of a beloved feature with readers who might never have heard of, say, Warren Tufts’ Lone Spaceman newspaper strip.

Some just wanted to be part of a social network filled with friends with similar interests. (And Jerry Bails, again, was in the forefront—forming a comics amateur publishing association: A club in which members contributed their own magazines to a monthly mailing.)

Science fiction fans (including us) usually used mimeographs to duplicate the material. (When will I ever put my stencil-cutting talents to use again?) But most comics fanzines in the 1960s tended to feature spirit duplication, thanks to many schools’ permitting their students to borrow the office’s Ditto machines. (Dittos, though most commonly purple, often let the publisher use a variety of colors; there were even yellow Ditto masters.)

And slowly, slowly, slowly … Amateur publishing began to look more and more professional. Some publishers used offset press resources. Eventually, even the professionals self-published.

Opportunities abounded. One high school kid in 1971 saved up enough money to produce The Buyer’s Guide for Comic Fandom. It wasn’t the first fanzine to be powered by ads selling back-issue comics—but it was one of the most stable, eventually surviving a transition to professional typesetting and production until 2013.

And several fans founded companies that published a variety of publications, including reprints of material that had long been out of print.

And more and more fan publishers became pro publishers. (Alter Ego—now hyphenless—still provides information and entertainment: a record-setter among such projects.)

And comics shops provided added distribution.

And then came the Internet.

And … Here we are. Social media no longer require postage or printing press. Reviews and news circulate in moments after writing. And comics beginners are continuing to find a pathway to communication with like-minded buddies.

All in less than 90 years.

What’s next?

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!