CAROUSEL BY JESSE HAMM

Carousel 033: J.P. LEON: An Appreciation

It is with a heavy heart that we present the last blog post from Jesse Hamm. It is a testament to his talent and legacy that his passing was mourned by so many individuals and organizations in the industry of which he was such a valuable contributor.

–Comic-Con

On the first of this month, we lost cartoonist John Paul Leon, age 49. Social media quickly filled with praise and laments from comics fans and professionals alike. If there had been any question of his greatness, it was firmly answered by the outpouring of appreciations by many of comics’ top luminaries. Clearly, he was an Artists’ Artist, revered by the best in the field.

Unfortunately, tributes on Twitter aren’t the ideal place to explain an artist’s merits, and readers new to Leon’s work might not understand what sets it apart. Today’s comics industry is full of impressive talents—why is J. P. Leon held up as a rare exception? I’d like to explore a few of the reasons he’s so highly esteemed, even among artists who themselves are considered great.

One thing that’s immediately apparent in Leon’s artwork is how well-researched it is. The settings, props, clothing, vehicles—everything is brimming with authentic detail. Where another artist might toss in a generic end-table or throw-rug, Leon shows that he’s done his homework: the curves, ornamentation, and designs on every piece of furniture, every curtain or lampshade, every industrial machine look as though Leon was standing there on the day, recording it all.

Not only is every likely structure and appliance present, but so are the odds and ends that accumulate around them: puddles of grease, scraps of paper, pens, towels, snacks, tissues—Leon included them all, making his worlds look more believable and lived-in than virtually any you’ll visit in comics. Consider this pharmacy scene (1). Details like the bottle of hand lotion by the register, or the Spanish translation (recoja) below the “pick-up” sign, would only be included by a careful observer, and they help bring the environment to life.

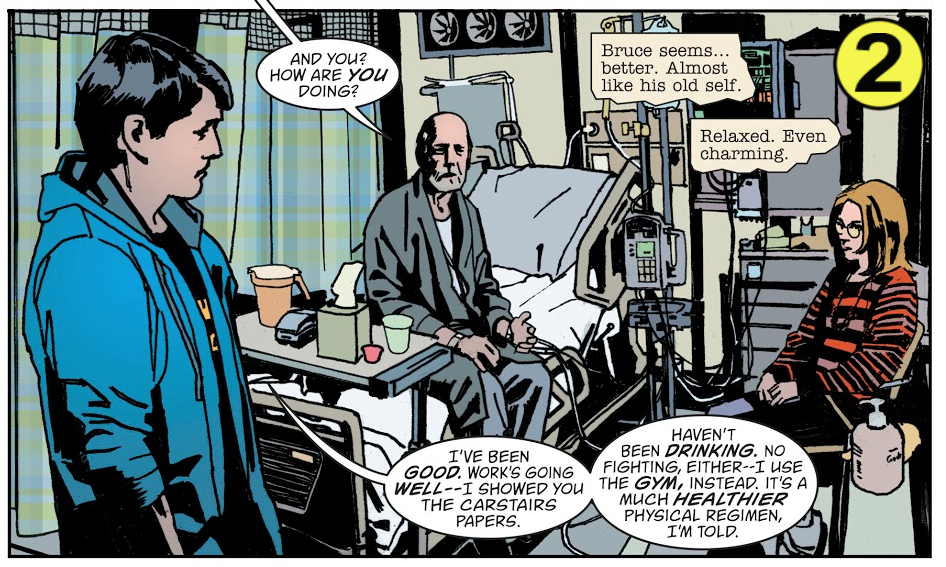

It’s also notable that he excelled at ordinary settings, such as this pharmacy, or the occasional law office or hospital room (2). Many artists will bring their A-game when drawing hot cars or spacecraft or other “sexy” subjects, but then phone it in when drawing anything “boring.” Leon instead seemed to relish the challenge of drawing every subject he put his hand to, whether ordinary or fantastic.

Another of Leon’s merits was his ability to force black areas into a scene.

I once spoke with a martial artist who was learning to solicit moves from his opponents. He had earlier learned how to rebuff the attacks his opponents freely offered him, but now he was learning how to corner his opponents into offering only those attacks he felt like rebuffing. He said he was learning to control the fight, instead of merely reacting to it. Visual art offers similar opportunities. When you’re first learning to draw, you try to understand where shadows would likely appear in a scene, and then you add them accordingly. But after mastering this approach, you’re free to improvise. You find that shadows may be added in unlikely places, not because they would necessarily appear there, but because your understanding of how light works enables you to plausibly fit them where you wish.

J. P. Leon was an expert at this. His scenes are often drenched with shadow—not added haphazardly or without credibility, but with the authority of a life-long student of light, who knows how to fit shadows plausibly wherever he wills them. Armed with this skill, he used shadows to lend weight to objects, tie scenes together, create mood, direct the eye—whatever served his narrative.

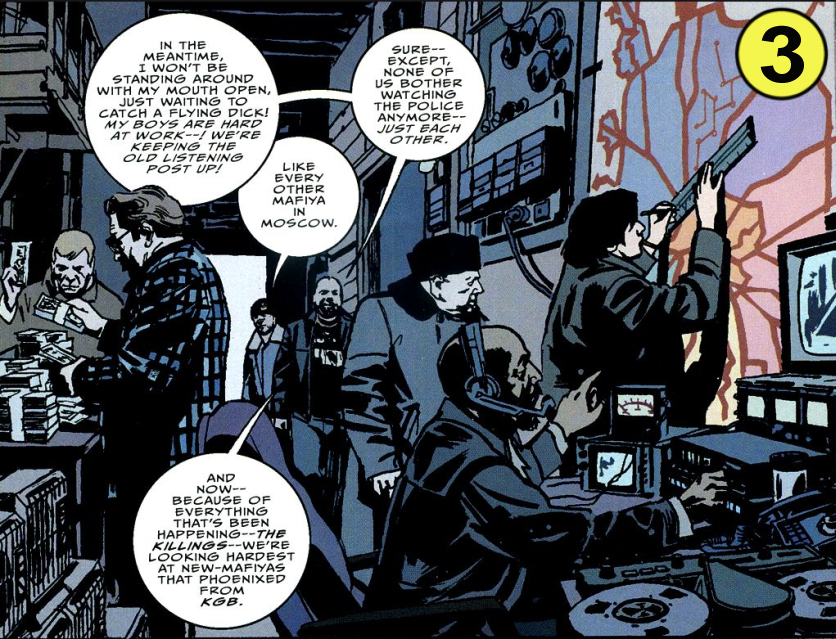

In this panel (3), the far wall is black, the ceiling is black, there’s heavy black on the nearest figures and equipment, and on the left wall—are all these heavy shadows justified by the lighting? Maybe, maybe not. But what’s important is that we believe they are, and that they serve the image.

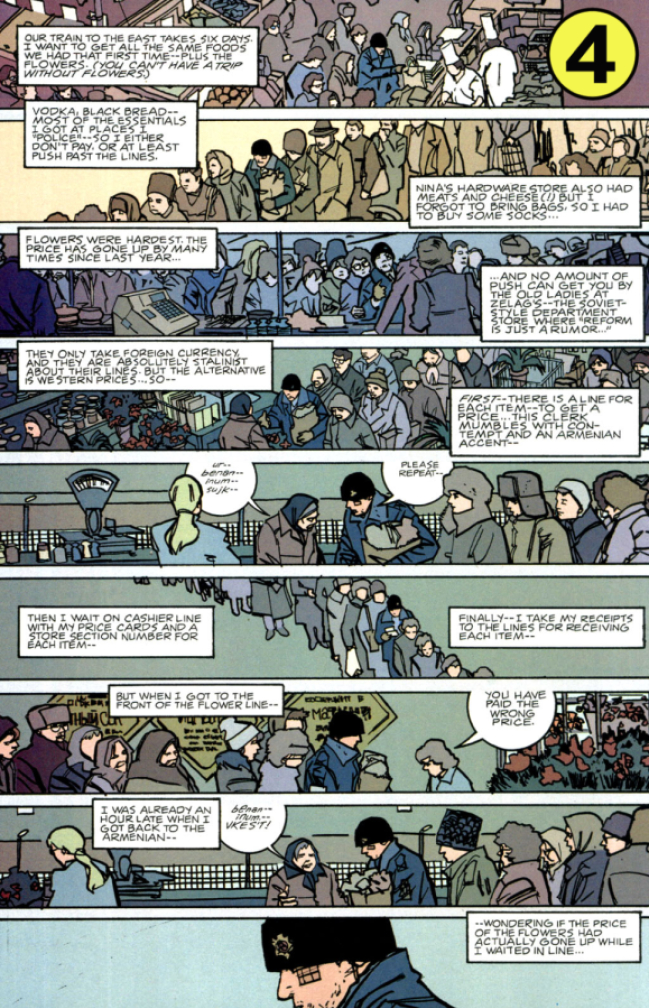

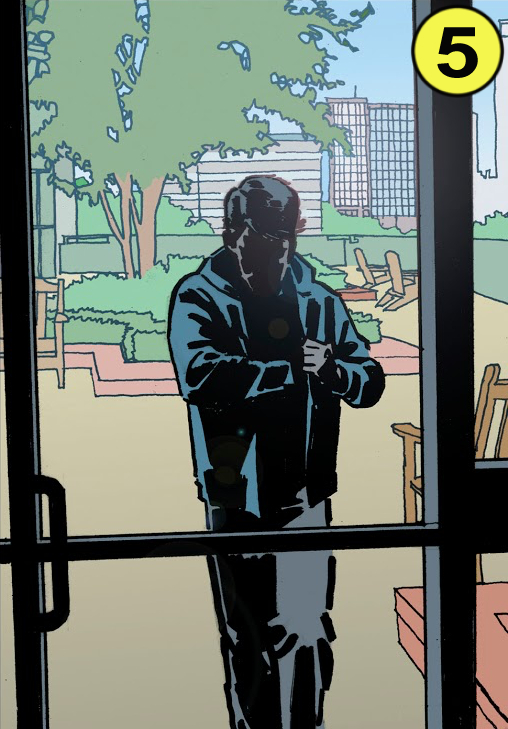

Not only had Leon mastered the use of black areas, but he used white to good effect, as well. In each panel of this crowd scene (4), he draws our attention to the black-hatted main character by rendering all of the other figures without heavy shadow. Or in this shot (5), he drops out all of the interior foliage of the tree, rendering it only in silhouette. This allows the reader’s eye to fall directly onto the main figure without undue distraction. He adds and subtracts detail and white and dark areas at will, controlling the visuals to serve the narrative.

In the examples cited above, you may have noticed another element which distinguishes Leon’s work: the rough character of his lines. Many artists who take great pains to draw realistically will carefully finesse their lines, giving great attention to every curve and texture, and rendering every contour with smooth precision. Leon avoided that approach. His lines are brusque, blocky, laid down in a quick, no-nonsense fashion, as though he’s sketching road directions on a napkin. His preference for this method has been shared by many other great draftsmen, including Alex Toth, Austin Briggs, Noel Sickles, and Robert Fawcett. Its advantage is a bold immediacy which is lacking in more polished art.

Leon clearly understood that the length, location, and angle of a line gives readers all the information they need to understand the form the line portrays. If those three attributes are handled properly, it’s unnecessary to add careful nuances or inflections to the lines. The reader doesn’t need to see delicate feathering, or precise little curves, because the accurate summary offered by the more basic linework is sufficient. We quickly grasp the character of each drawn object and move on to the next.

Few artists have the courage to rely so heavily on such rough linework as Leon did. The temptation to “help” the drawing along with finer lines is unrelenting. When you don’t know exactly where a line should go, or the correct angle needed to portray the underlying form, it’s so comforting to hide behind some extra feathering and fancy inking. And even when you know your lines are correct, it’s hard to trust readers to know they are correct. What if readers won’t understand these simple, unadorned lines? Maybe they need to see more fussy nuance? Leon was not vexed by such questions—or, if he was, he chose to ignore them. He knew where to place each line, and he let it speak for itself: gruffly and frankly.

Leon rarely tied himself to an ongoing series, more often drawing sporadic single issues, so his work can be difficult to find. To those new to his art, I recommend the trade paperback Batman: Creature of the Night, collecting a recent four-issue series he drew for DC. There, you will find hundreds of pages of prime John Paul Leon to enjoy, well worth your careful attention.

Image credits:

- Ex Machina Masquerade Special #3, copyright 2007 Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris

- Batman Creature Of The Night book 4, copyright 2019 DC Comics

- The Winter Men #4, copyright 2006 Brett Lewis and John Paul Leon

- The Winter Men #1, copyright 2005 Brett Lewis and John Paul Leon

- Batman Creature Of The Night book 4, copyright 2019 DC Comic