STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 047: Early Kirby Exposures

This August will be the 100th anniversary of the birth of Jack Kirby. My main exposure to Kirby’s work was through a small pile of comics and reprint books I acquired as a child. Most of them were torn, coverless and incomplete, and I read them over and over until they were as fragile as moth wings.

With the exception of a few stories reprinted in Stan Lee’s Origins of Marvel Comics collection, I rarely had any sort of context for the Kirby stories I encountered. I could only buy comics at thrift stores and flea markets, so I almost never read two issues in a row of anything. If a story was “to be continued,” I’d just have to guess what happened next. If the comic featured “part two,” I only had a bit of recap to tell me what had happened in part one. Not a fair way to encounter an artist’s work when they’re often telling serialized stories.

Nevertheless, I was always drawn into the slices of Kirby’s stories I could get my hands on. I was fascinated by the action, the imagery, the mythic feel of larger-than-life conflicts. I was also a little scared by some of it. Most of the comics I read were friendly and inviting, full of pictures composed to convey a sense of sports-hero athleticism and television glamour. Kirby’s work served up a different menu: his characters didn’t look or behave like those in other comics. They seemed like they were formed out of granite, or hard rubber, or cooling lava. They stomped and leapt with wild, explosive movements and contorted themselves into agonizing shapes. They paused to pose like roman statues and deliver soliloquies, then relaxed and kidded around with each other like my friends at school did.

I thought it might be worthwhile to take a close look at some panels I remember from back then, analyze them with what an eye for what I’ve learned about comics storytelling, and try to recall the impact they had on me when I first saw them as a pre-teen.

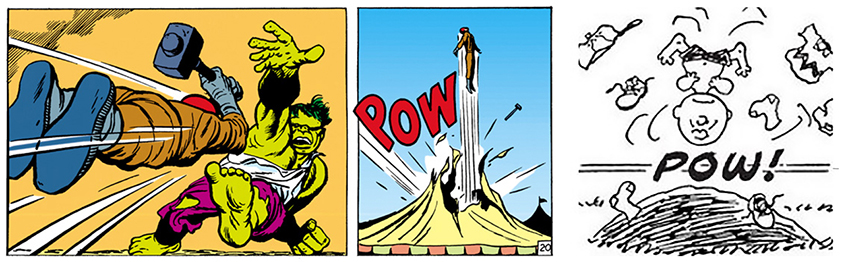

This one is from a Hulk comic. I obsessed over it for a while. It felt like one of the biggest punches I’d ever seen in a comic, but we never actually see it. The key action in the sequence (Hulk punching the guy flying at him) happens between the panels. I might’ve seen something like it before in a Peanuts cartoon, but this was the first time I found myself aware of how powerful it can be to make the reader fill in the blanks.

Looking at it now, I can see just how much Kirby did to make that sequence work. In the first panel, the guy with the sledgehammer is large in the foreground, and brandishing a heavy-looking weapon. (It’s not Thor’s hammer, though the design is similar.) This is necessary to make him a credible threat to a big monster like the Hulk. He’s hurtling through the air at Hulk like a cannonball, so it’s clear that Hulk only has a moment to act. Hulk’s gesture communicates that he is off-balance, but still ready for what’s coming at him, and that big green left fist is low to the ground, so we know he’ll be swinging it upward. That’s the kind of blow that might knock his attacker into a new trajectory.

In the next panel, that POW is there both for clarity, and for rhythm. Clarity: the sequence doesn’t quite work without the sound effect. In a world full of superheroes, the reader couldn’t be sure whether the guy with the hammer was punched, or if he just changed his mind and decided to fly through the top of the circus tent rather than face an angry Hulk. Rhythm: that POW is the beat that feels like an impact between two moments of movement.

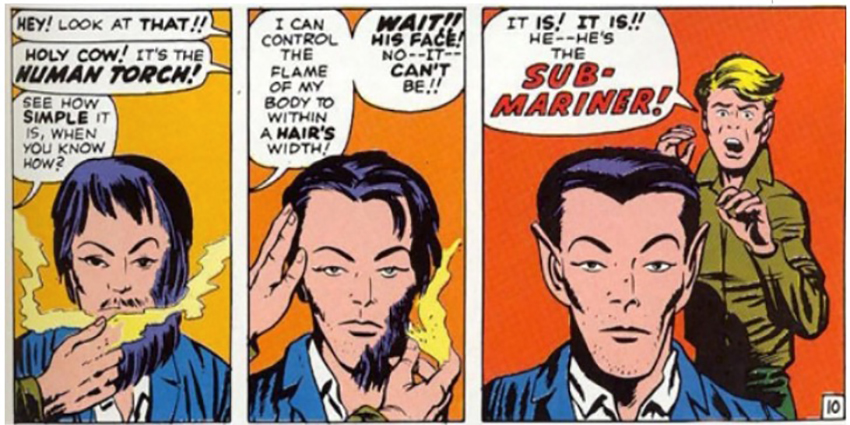

Another favorite Kirby image was this one, from an issue #4 of Fantastic Four, in which Stan Lee and Jack Kirby reintroduced Bill Everrett’s character the Sub-Mariner.

We’d been introduced to a mysterious bearded hobo who was winning a skid row brawl against impossible odds. Then Johnny Storm gave him a shave.

This was a fascinating sequence. I liked Johnny use of a fantastic power to do something as ordinary as giving a guy a shave. And I knew who the Sub-Mariner was because he was in the very first comic I’d ever read, but even if I hadn’t, I’d have known this was an important revelation. Prior to this moment, the comic was full of wild action and dramatic camera angle changes. That Kirby suddenly stopped and devoted three panels in a row to a static shot of a guy getting his beard shaved off made it perfectly clear that this was a crucial moment to witness.

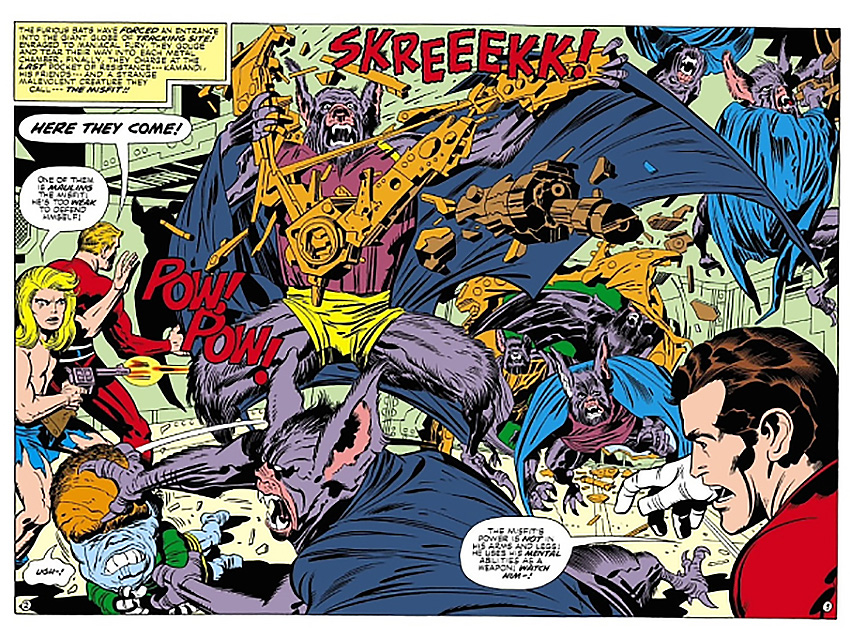

As a very young reader in the mid 1970s, I found that the reprints I read of Jack Kirby’s work from the ‘60s to be mostly friendly, funny and inviting. His new work in the ‘70s was mind-blowing and scary. I didn’t always know how to process his images. The monsters and machines were wild and unlike anything I’d seen in any medium. The stakes seemed life-or-death at every moment. This splash from Kamandi has huge terrible monsters at the center. They outnumber the heroes, who are separated from each other, pushed to the very margins of the page. The good guys seem entirely ill equipped to handle this onslaught, and nothing that they are doing is helping the situation at all. The bat creatures’ movements on the page are explosive and thrust violently in multiple directions, creating a sense of chaos. Nothing about this image was comforting to me as a young reader, and there was no indication that anything would turn out all right. This is as it should be in a Kamandi story, of course; it’s set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland where humanity has been all but wiped out. But I was seven years old and new to the genre. I doubt I’d ever seen an image in any medium where things seemed so dire for the heroes.

This final image was also from the 1970s. It’s the opening splash of a story from Kirby’s series The New Gods, and while the rest of the story is every bit as much chaotic and violent as that Kamandi panel, this picture struck a note I didn’t expect. Despite Kirby’s monumental figures, it’s more like a drawing from a romance comic than the intro to a story about the war between two cities of Gods. Izaya and Avia sit back-to-back, sharing flirtatious sideways glances in an impossibly idyllic garden. There’s a waterfall and garlands of flowers and a passing dove. The two warriors look comfortable and utterly at ease, her body curling into his as she strokes him with a feather. Their bodies together form a shape like the base of a pyramid, accentuated by the angles of Izaya’s staff and Avia’s lower leg. But within that pyramid the shapes all flow in uncharacteristically gentle curves. This was probably the first time I’d seen an indication of what these warriors were fighting for.

I didn’t know at the time that Kirby was one of the inventors of the romance comics genre. He had the tools to communicate connection every bit as well as conflict, and he knew when to use them. That’s what I see in Kirby now, remarkable craft in the service of an unfettered, world-class imagination.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!