MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 036: Goofy Heroics of the Code

When characters in masks and capes fought villainy in the early days of comic books, their goals pretty much involved defeating bad folks. With stories that seemed inspired by the likes of newspaper strip crime-fighter Dick Tracy, they tackled, often with grim determination, such foes as counterfeiters, bank robbers, spies, and similar menaces to society.

But villainy might invite imitators. And, lacking a local Batman to keep them in line, kids might be tempted to steal an auto, rob a till, or hold up a classmate for lunch money. Longtime critics of comic books soon expressed concerns. After all, what with the majority of an entire generation of kids reading comics, if an image provided an example of bad behavior, its audience might copy the transgression. This is not to say that the guys and gals in costume weren’t involved in other adventures that included endless maintenance of the secrecy of their civilian identities. Or weren’t on the lookout to prevent the demise of an accident-prone buddy. Or never had an oddball character from another dimension gum up day-to-day routines. But when challenges reflected real-world villainy that might inspire imitation? That was, critics said, a problem.

Superman Heroics Were Out

When Chicago Daily News Literary Editor Sterling North called comic books “a national disgrace” in a widely reprinted essay in 1940, he cited “Superman heroics” as a component of the “lurid publications” that depended for their appeal “upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction.” It was part of a growing attack that grew through the years into anti-comics campaigns that focused on driving comics out of department stores, grocery stores, pharmacies, and countless other venues where kids might have easy access to four-color fun. By the end of 1954, to save itself, the comic-book industry sent its output to the nursery. “No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.” “No unique or unusual methods of concealing weapons shall be shown.” “Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly nor as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.” The Comics Magazine Association of America, Inc., introduced a Comics Code that was applied to all material from its members. Some super-character publishers quickly gave up their rosters of heroes for a variety of reasons: Fawcett’s Captain Marvel, Quality’s Plastic Man, Hillman’s Airboy, and many others didn’t survive. Funny animal and little kid titles took their places. The loss of sales venues, public pressure, competition from free television entertainment, and the Code drove several publishers out of the field.

In the ever-fewer comic book outlets, readers found a change in their comics heroes.

What Was In?

Some adventure comics editors and writers had already worked on science fiction and fantasy pulp magazines. Superman co-creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had been active science fiction fan publishers; others from that field included Mort Weisinger, Julius Schwartz, Otto Binder, Kendall Foster Crossen, Ed Hamilton, H.L. Gold, and Gardner Fox. Several nimbly adapted to the new challenges, providing stories that grew more and more goofy in 1955—less and less focused on tales of realistic crimefighting.

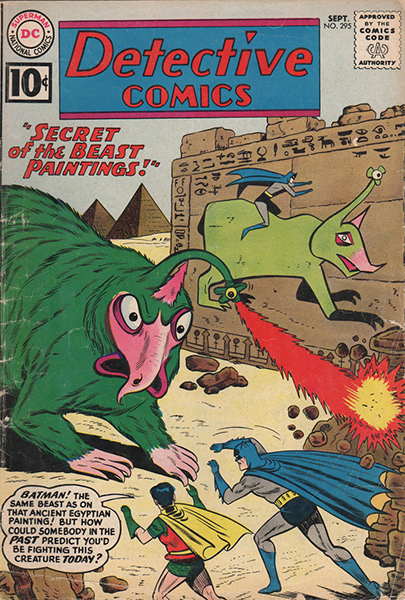

DC didn’t desert all its characters, but the covers of Batman went from the villainies of gun-wielding crooks to a variety of oddball events, the introduction of a “Bat-Hound,” other heroics, and (yes) the never-ending need to protect the heroes’ secret identities. There were fewer and fewer archenemies and more and more dinosaurs, aliens, and challenges from an other-dimensional prankster.

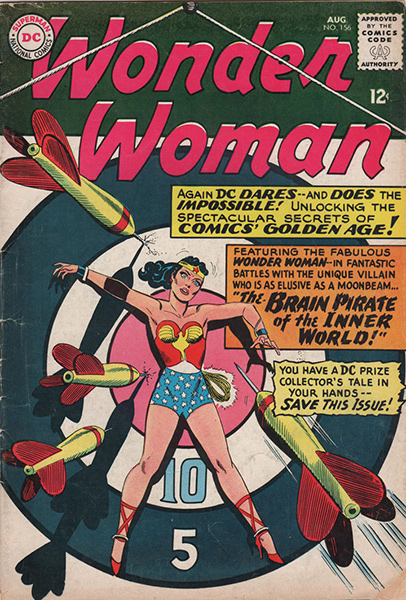

Wonder Woman was already founded more in fantasy than the real world, and the Code left her bathing-suit outfit pretty much as it had been. But her routine of playing bullets-and-bracelets with crooks and spies, so frequent before the Code, grew fewer. She was soon focusing on such challenges as performing in a rodeo, competing in super-contests, teaching a gorilla, and, yes, maintaining her secret identity.

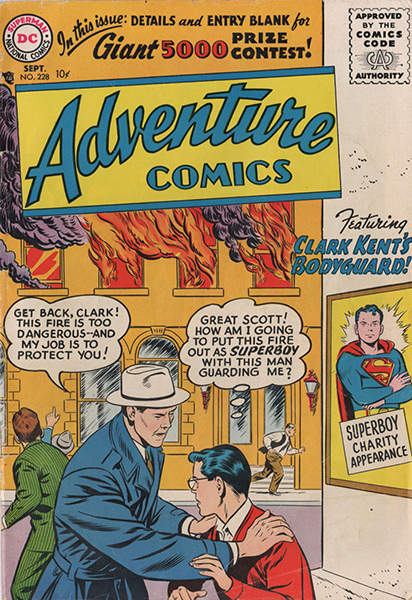

As for Superman: His Superness, too, had already involved fantastic conflicts less likely to inspire juvenile delinquency, but there were also many tales of weapon-toting nasties. Then, the Code seal appeared on the cover, and so did the other-dimensional Mr. Mxyztplk, introduced a decade before. Soon, stories featured space invaders, giant animals, goofy kryptonite variants, Bizarro, and more. Oh, yes—and secret-identity stories galore.

Dinosaurs and gorillas soon ran amuck in more and more of DC’s series—even in such unlikely venues as Star Spangled War Stories and the Revolutionary War tales of Tomahawk. So did sidekicks and the challenges they provided. A metaphorical tidal wave of non-violent stories overwhelmed the content, many based on a sidekick and/or girlfriend behaving (to put it charitably) unwisely.

And Marvel?

Marvel’s business model seemed to be to look for genres that were succeeding for other publishers and then to flood the market with similar series, focusing on its own versions of teen titles, Westerns, and the like. But superheroes didn’t do particularly well in the few experiments editor Stan Lee tried between the end of World War II and the onset of the Comics Code. When he tried morphing the Young Men title (featuring boxers, hot rods, and basic training) into a superhero title with a return of the Human Torch, Submariner, and Captain America, it ran only five more issues. And Captain America’s own title had begun in 1941 and run till 1949. When Lee tried him out as a Commie-smasher in 1954, Captain America ran only three issues (May-September) and ended as the Code was imposed. He tried other sorta-super Marvel characters in such series as Marvel Boy, Lorna the Jungle Queen (later, Lorna the Jungle Girl), Black Knight, and Jann of the Jungle. Hey, even super-villain Yellow Claw had a brief four-issue, Code-approved title in 1956 and 1957.

But it took a variation of DC’s superhero revivals to bring Marvel back into super-hero prominence. DC had revamped Flash in 1956, Green Lantern in 1959, and the Atom in 1961. The super-genre having clearly demonstrated its commercial possibilities, Lee introduced The Fantastic Four. By the third issue, the super-powered team not only got its super-suits, it also got a price hike—from the standard dime to a whopping 12 cents per issue.

And the future lay ahead. As it does.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!