MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 038: The Little Red Hen

We know the story, right? The little red hen finds the wheat, asks her friends for help planting it, they say they won’t help, so she does it herself.

And harvests it and grinds it to flour and makes the bread and bakes the bread—each time asking for help, each time being rejected. When she asks who will help to eat the bread, her buddies happily volunteer—at which point, she says she can manage to eat it all by herself, thanks anyway.

Walt Kelly featured the hen in an issue of Easter with Mother Goose. King Aroo cartoonist Jack Kent provided a delightful version in Jack Kent’s Book of Nursery Tales. In the case of the former, I bet Kelly produced his work “for hire.” In the case of the latter, I bet Kent was paid royalties. In both cases, the creator depended for payment and circulation on his publisher: Western Printing & Lithographing Co. for Kelly, Random House for Kent.

We’re accustomed to that arrangement in the world of comics, but it isn’t the only way comics have been produced.

Centuries Ago

Ben Franklin was a Little Red Hen. He used to sign his letters as “B. Franklin, Printer” and he invented the first newspaper chain. And he created the classic “Join, or Die” political cartoon that was printed in 1754 in his Pennsylvania Gazette.

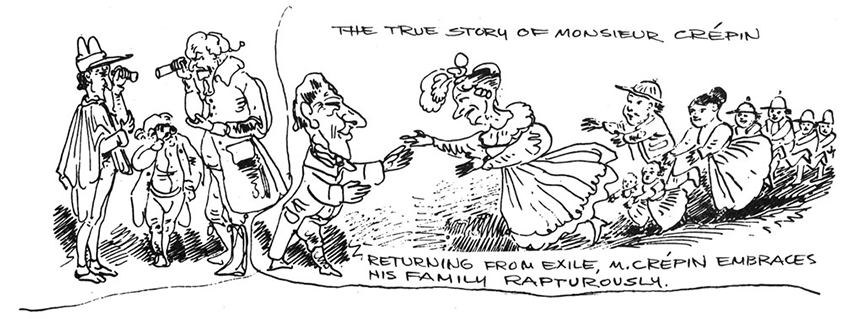

Comic-art pioneer Rodolphe Töpffer used lithography to solve the challenge of making multiple copies in an art form that combined freehand line drawings with hand-lettered text. Though Töpffer’s writings were widely seen in others’ publications, he produced that ground breaking comic-book work through his own comedic lithographs. They reached enough other people that they drew encouragement from such critics as Goethe—and earned him the eventual international reprinting of 1837’s Histoire de M. Vieux Bois as The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck.

It didn’t take long for creators who wanted to combine their drawings with storytelling to decide that the biggest bucks would probably come from getting a paycheck from a publisher, rather than from the challenges of self-publication. Although Winsor McCay produced his own animated films (and invented animation tricks to do so)—he eventually turned to his salary from Hearst rather than another form of self-publishing.

Black and White Boom

It could be argued that the do-it-yourself possibilities of comic art became attractive again via the avenues of self-publication available to producers of fanzines and underground comix, the latter starting with such publications as Zap Comix. Heck, fanzines were self-publishing almost to the point of the Platonic ideal: You want it published? Find a school Ditto machine or learn how to cut mimeograph stencils, and away you go! Nevertheless, in many cases, creators continued to seek out ways to market their work to professional publishers, which dealt with such matters as printing, circulation, and payment.

Eventually, though, direct market comics shops offered a distribution network through which even individual creators could market their self-produced stories. Without going into the details of boom and bust and digressing into matters of distributor competition and the like, let’s note a few of the successes. Keep in mind that the Little Red Hens in question were often aided by one or more people in a support group; the point is that they put together their own organizations to bring their creations to market. (And, no, this isn’t a list packed with detailed descriptions; if you’ve never heard of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, for instance, there’s an abundance of information at the touch of a Google search. Nor, of course, is it by any means an exhaustive list.)

In Chronological Order, Then …

- 1976: American Splendor by Harvey Pekar.

- 1977: (December) Cerebus by Dave Sim.

- 1978: Following publication of the first installment in Fantasy Quarterly (from Independent Publishers Syndicate) in February 1978, Wendy and Richard Pini took their Elfquest as their own project for WaRP Graphics, starting with Elfquest #2.

- 1980: Maus by Art Spiegelman.

- 1984: TMNT (May) Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird produced a satire of Frank Miller’s work on Daredevil. Their Mirage Studios released Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1.

- 1984: Usagi Yojimbo (November) first appeared in Thoughts and Images’ Albedo Anthropomorphics #2, moved to Fantagraphics, and then appeared wherever writer-artist Stan Sakai chose.

- 1991: (July) Jeff Smith’s Cartoon Books released Bone #1.

- 1993: (January) Strangers in Paradise by Terry Moore.

- 1993: Wandering Star by Teri Wood.

- 1995: Stray Bullets by David Lapham.

Wups! I Went Right by …

1992: Image Comics—The enterprise experienced complex ins and outs but was founded to enable self-publication by Erik Larsen, Jim Lee, Rob Liefeld, Todd McFarlane, Whilce Portacio, Marc Silvestri, and Jim Valentino.

Today

There’s an additional method through which comics creators publish and distribute their own material. Look online for self-produced comics, several of which have been on the Internet for years now. Whether it’s Wondermark by David Malki (starting in 2003), The Oatmeal by Matthew Inman (starting in 2009), or the work of Eisner Award-winner (for 2014’s “When the Darkness Presses”) Emily Caroll, gifted individuals have begun to populate the Internet. And support of their entertainment can, similarly, spread virally.

Tomorrow

Who knows? I’ve lost count of the parents who have come to me to ask what possibilities might be Out There for their kids who “just want to make comics.”

I would caution creators with something science fiction and fantasy writer Theodore Sturgeon once said. When an accountant asked him who had done his taxes, Sturgeon responded that he’d done them himself. To which the accountant replied, “But any accountant could do your taxes. You’re the only person who can write stories by Theodore Sturgeon!”

Maybe that’s another aspect of the situation. Creators can look to others for support—while they remain in control of what they do.

If you are a comics creator, is it time to do it yourself?

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!