MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 074: School Days

Back In The Day, September meant summer was over, and it was time to turn from vacation to books.

Including comic books. Because we could continue to read just for fun, even as we opened textbooks devoted to math, science, and history.

Then

In the 1940s and 1950s, few public schools encouraged students to look at comics as part of their quest for knowledge—though Jim Shooter has noted on his website that he learned many “new words” from the four-color world. He specified “bouillabaisse,” found in a Donald Duck tale and used to win a gold star in a “good word” competition in first grade in the 1950s. “I knew what indestructible meant, could spell it, and would have cold-bloodedly used it to win another gold star if I hadn’t been banned from competition after bouillabaisse.”

In the comics themselves, Archie Andrews became involved with challenges at Riverdale High School in the second adventure after his introduction. The first story had been by Vic Bloom and Bob Montana in MLJ’s Pep Comics #22 (December 1941). Soon, the teens’ interactions with principal and teachers became a fundamental basis for adventures of Archie, Jughead, Reggie, Betty, and Veronica.

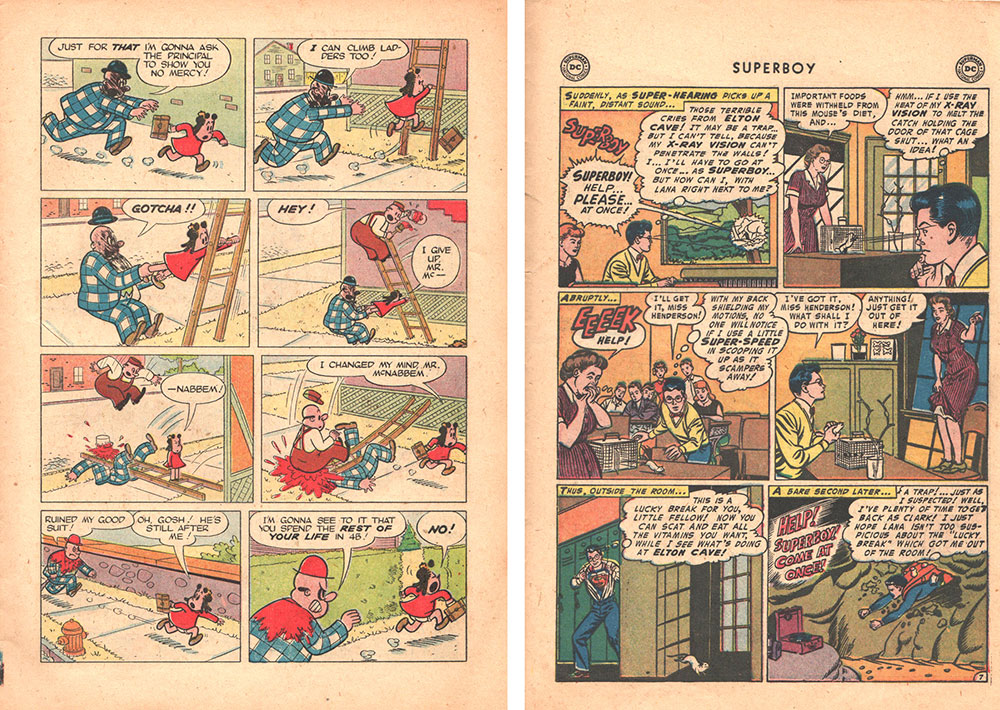

Marjorie Henderson Buell’s Little Lulu was introduced in 1935 as a prankster in her first appearance in The Saturday Evening Post. In the John Stanley stories offered in Dell’s comics line, she was shown to be a girl who aimed to do her best in school. Nevertheless, story after story featured her in farcical conflict with the school’s truant officer, eventually dubbed Mr. McNabbem.

Some superheroes had school adventures years before Peter Parker was bitten by that radioactive spider and a bunch of mutant kids ended up at a certain professor’s academy. DC’s Superboy #75 (September 1959), for example, was obviously a back-to-school issue. It included the cover-featured “The Punishment of Superboy!” by Otto Binder and John Sikela in which Jonathan Kent tried spanking the invulnerable kid. It also included “Superboy’s First Day at School!” by Otto Binder and George Papp. (Uh oh! Don’t reveal those powers, Clark!)

But did public schools take such endorsements as a reason to encourage their students to read comics?

Let’s just note that many schools had a policy endorsing teachers’ confiscations of students’ comics.

Although …

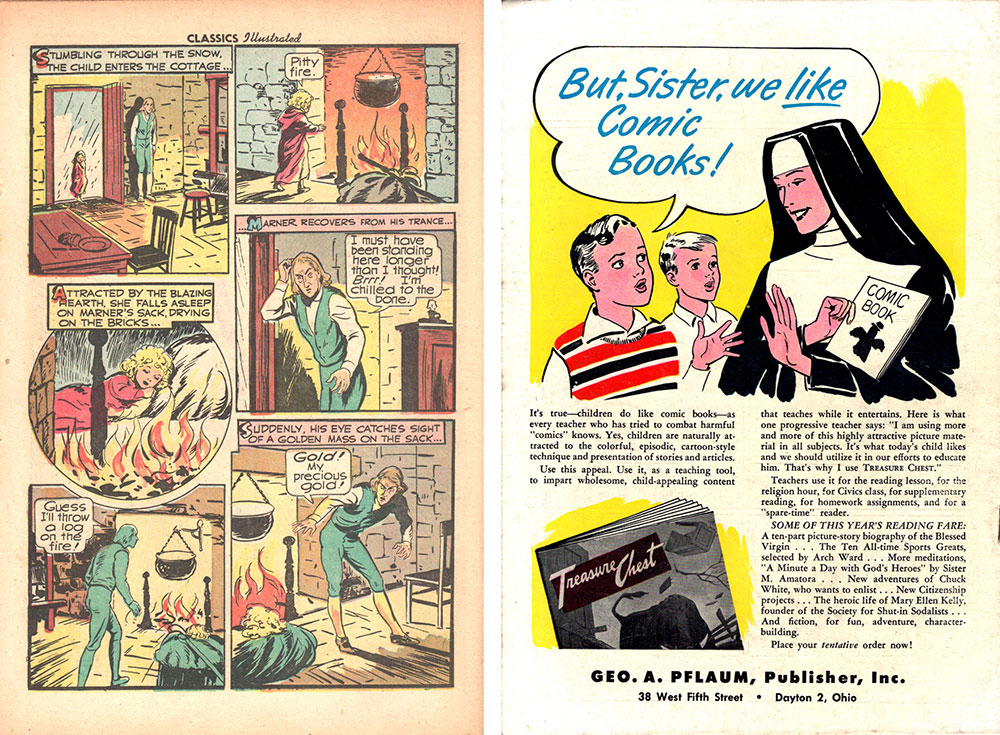

Mind you, one group of educational institutions did encourage its attendees to read comic books. Many parochial schools offered students the opportunity to order copies of Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact. It was nearly six years after Sterling North had called comic books “a national disgrace” and “a poisonous mushroom growth” that the 32-page first issue of Treasure Chest of Fun and Facts was published. The plural of “fact” was later to become singular; in any case, it was dated March 12, 1946. Some of its contents were religious in nature (“God’s Gift Is Lent,” a history of Shrove Tuesday, etc.); some consisted of other entertainment.

Among other early education-associated comics were what became titled Classics Illustrated releases, which had begun (as Classic Comics) about five years before Treasure Chest. Circulated at newsstands, their guilty attraction for some consisted of their possible use as a substitute for school reading assignments.

How much of that series’ circulation came from such education-dodging? For example, many junior-high students before, during, and after the 1950s found George Eliot’s Silas Marner on their required-reading list. In 1949, Classics Illustrated #55 offered the option of a four-color simplification, with script adaptation by Harry Glickman and art by Arnold Lorne Hicks. Some kids figured out that a book report might be cobbled together by the trick of referring to many of the descriptions in the captions. How did Eppie come into Marner’s life? “Attracted by the blazing hearth, she falls asleep on Marner’s sack, drying on the bricks.” Sales justified sending the title back more than 10 times for new editions. (Mind you, savvy teachers became aware of how to look for some of the shortcuts. For example, citing lack of room, the version of Crime and Punishment in #89 omitted both the heroine and the point of Dostoyevsky’s novel.)

Why Comics?

Slowly over the years, graphic stories began to find a more secure place in education. The combination of picture and text to convey information can draw many new readers to fiction and fact. And public and school libraries often contain a variety of entertainment- and information-packed comics as part of their collections.

There’s content for older readers, too. I recently bought one of Larry Gonick’s Cartoon Guide series for one of my grandsons and me. I love the clarifying picture Rick Geary provides in his dark histories. (You liked Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City? Try Geary’s The Beast of Chicago for an illuminating view.) And there’s much more.

I’ve selfishly recommended Scott Robins’ and Snow Wildsmith’s A Parent’s Guide to the Best Kids’ Comics in the past. I say, “Selfishly,” because I helped put it together in 2012; yes, it now cries out for an update. Because, wow, the hits keep on coming.

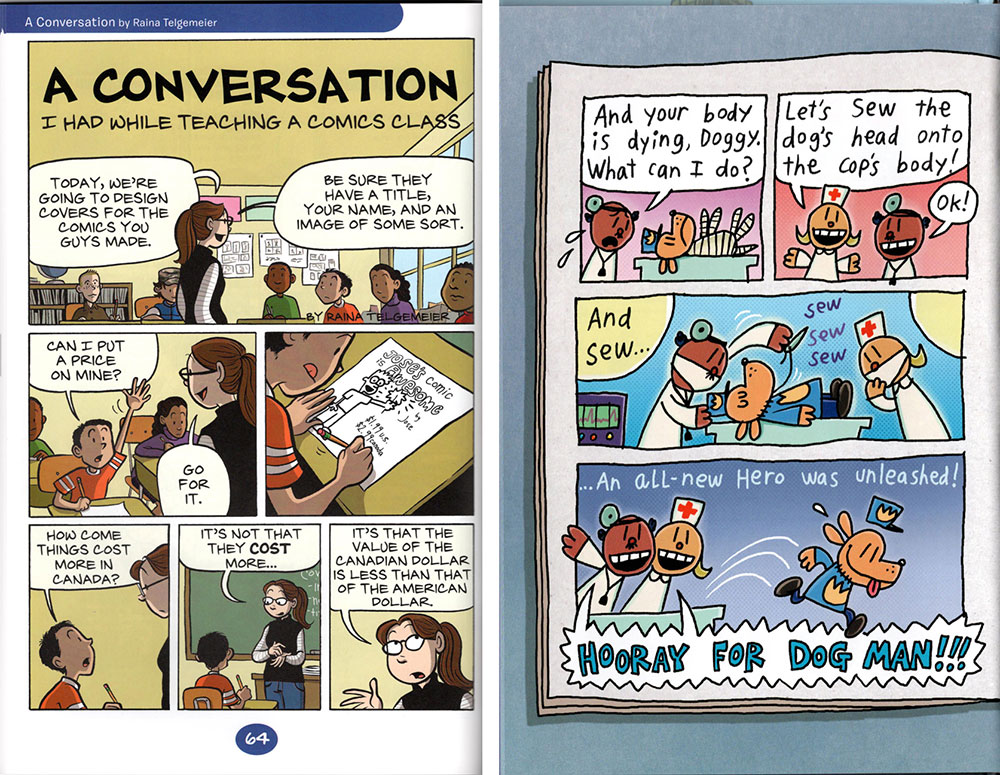

The bookstore chain Barnes & Noble devotes many feet of shelving to comics, many of them comics aimed at young readers—including stories of school adventures. Some are even designed to inspire kids to make their own. Her webcomic Smile quickly took award-winning Raina Telgemeier into the world of graphic novels. Jeff Kinney’s “Wimpy Kid” books combine pictures and text to deal with kids’ challenges today—and encourage them to keep their own picture-packed diaries. Heck, nearly a decade ago, the Reading with Pictures anthology cover-featured the summation “We get comics into schools and get schools into comics.”

These Days

Among other points to consider, when it comes to school-connected comics, consider that early 20th century adage “A picture is worth 1,000 words.” In comics, we get both, with pictures elaborating text.

In fact, today’s comics world might even challenge one of the long-time basics for advocating comics for kids. We used to say that comic books make it clear to a young audience that reading is for entertainment, as well as for information. “Teachers,” we used to say, “don’t assign comic books to their students.”

These days? Many teachers do exactly that.

And that’s a good thing.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!