MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 090: 1961

In this 90th “Maggie’s World,” it seems appropriate to look at milestones. And hey! April 2021 is a pop culture anniversary of sorts.

Thanks to Comic-Con’s archive of “Maggie’s World” columns, readers can visit my earlier comments on the history of the world of comics collecting. The #32 (September 2015) outing was titled “55 Years and Counting,” And #39 (April 2016) was “2016 Fanniversary 55.”

And now it’s April 2021: time to celebrate a milestone again—and remember more.

Six decades ago

In #32, I summed up some of what it had been like for comics lovers when comics fandom got under way. “What was the meaning of Billy Batson’s magic word? Didn’t Mary Marvel have a different meaning for the same magic word? … The public had forgotten. Just … Forgotten. … Although we’d been able to buy copies from newsstands less than a decade earlier, by September 1960, such treasures could be found only in second-hand shops.”

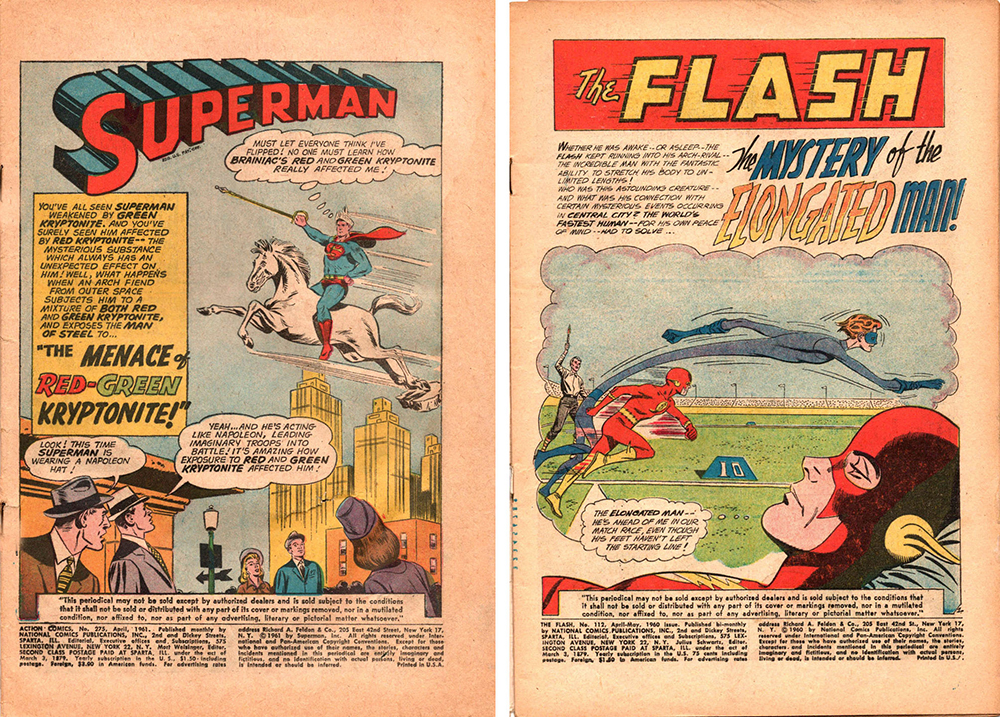

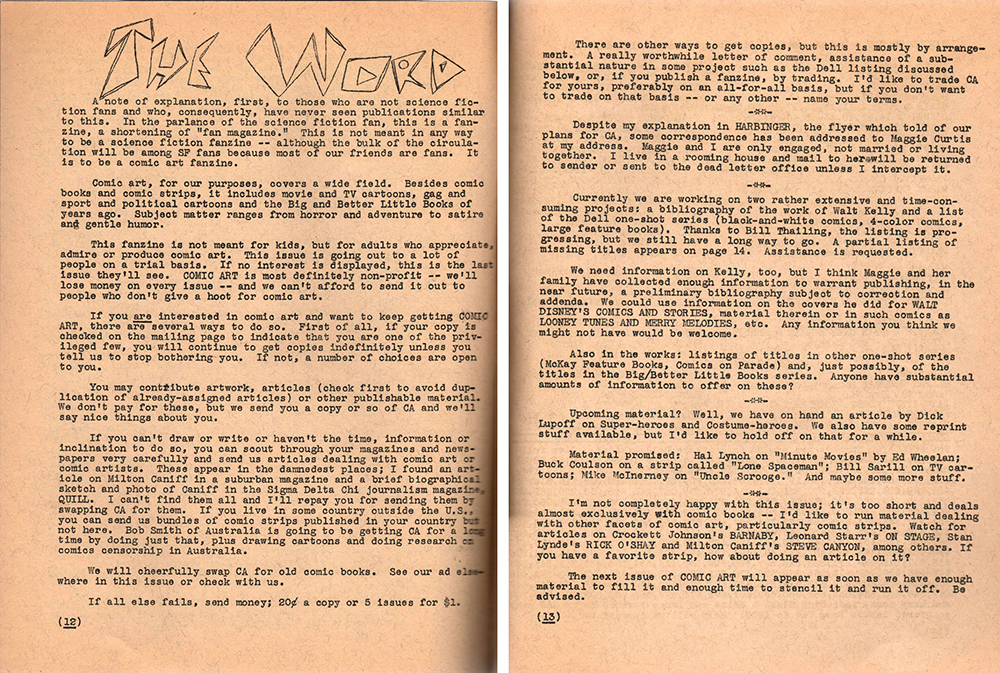

In #39, I paid tribute to the anniversary of the first comics fanzines (released in spring 1961) that were soon joined by many, many others: an environment that would grow into a continuing, influential world of publications focused on the artform. (And, by the way, the spring of 1961 itself was the 35th anniversary of Hugo Gernsback’s science fiction magazine Amazing Stories, in which were published names and full addresses of science fiction enthusiasts. That quickly united a national community of sf fans—including Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who would go on to co-create Superman.)

So consider the extent to how much we didn’t know in early 1961.

To begin with, we had had almost no reference material to consult for the facts. A few library books were available (if the local library collection happened to include them). I bet I’ve listed them before, and their primary focus was on comic strips, but in any case:

1942 Martin Sheridan, Comics and Their Creators (Ralph T. Hale): strips, one chapter on Superman, one chapter on animated cartoons

1943 Thomas Craven, Cartoon Cavalcade (Simon & Schuster): cartoons and strips

1947 Coulton Waugh, The Comics (Macmillan): strips, one chapter on comic books

1959 Stephen Becker, Comic Art in America (Simon & Schuster): strips, one chapter on comic books

Oh, there was one book that focused on comic books, but it was not in admiration:

1954 Fredric Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent (Rinehart)

In fact, it was part of the reason that nostalgia played such a large part in activating comic book collectors a few years later. Because it changed the types of comic books that were on newsstands.

With that as a foundation …

In 1961, we had nostalgia and a few dealers specializing in back-issue books and magazines. That’s what Dick and Pat Lupoff had started with in 1960 in their science fiction fanzine Xero #1, which contained the first installment of the comics-focused series All in Color for a Dime.

What we had as reference material was what we’d hung onto through the years and what was currently on the nation’s newsstands.

Comics that were cover-dated April 1961 came from these publishers with roughly this many titles:

- 2 American Comics Group

- 2 Prize

- 9 Archie

- 11 Marvel

- 15 Harvey

- 27 Charlton

- 28 DC

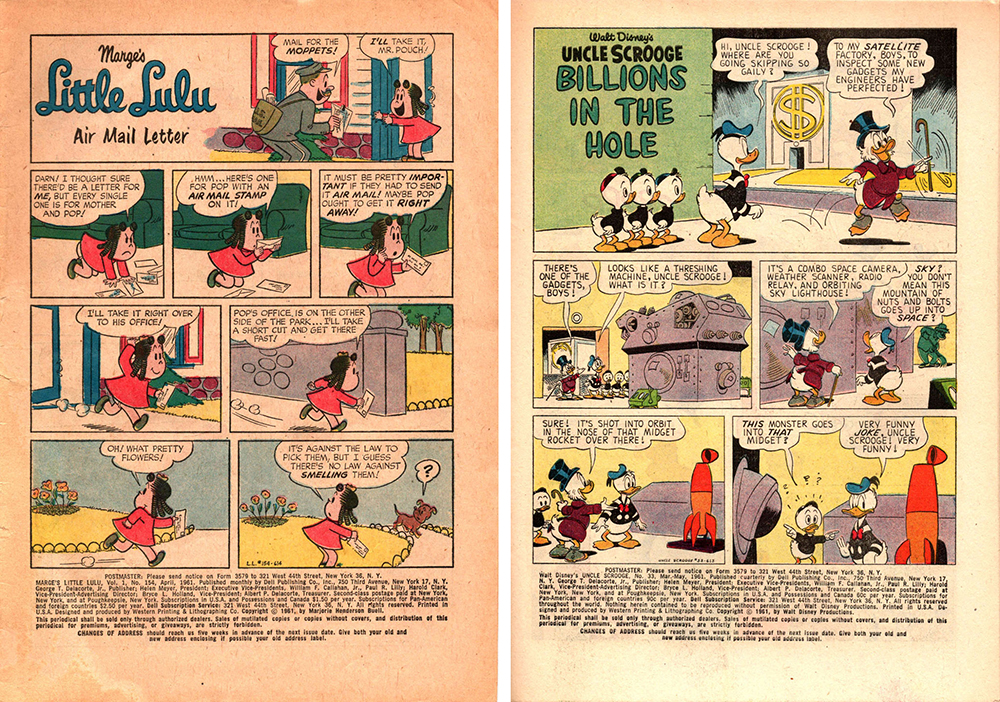

- 28 Dell

Added to those were George A. Pflaum’s Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact and Gilberton’s releases of its Classics Illustrated and Classics Illustrated Junior titles with their own distribution channels.

Figuring that there were 124 or so titles out there—with the contributor credits on many (most?) hidden—there were a lot of questions to be answered and—with newsstand comic books having begun a little over a quarter-century earlier (in 1934)—a lot of history to be explored.

One information source for fannish researchers was the Statement of Ownership that periodicals circulated via second-class mail were required to post. For 1961, we could eventually see such figures for average paid circulation per issue as:

- Forbidden Worlds 178,600

- Richie Rich 220,000

- Showcase 240,000

- The Brave and the Bold 245,000

- Archie 458,039

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan 509,355

And (though new to the game) we could guess at which companies were approximating their figures. And which titles were doing well. And, yes, analyses could be tricky. For example, Uncle Scrooge #33 [March-May] had an average circulation that topped the field at 853,928 per issue, according to today’s Comichron website. Comichron (from which I grabbed this data) points out that Uncle Scrooge’s circulation was highest—but it was a quarterly. More time on the newsstand meant more time to find and buy a copy.

Also of note regarding sales that year: Comichron’s John Jackson Miller says, “The average [mean] circulation of all titles publishing Statements was above 300,000 copies for the last time in 1961.”

Mind you, the Silver Age is generally considered to have begun years before, with DC’s Showcase #4 (September-October 1956). But—look at its name—it just provided trial balloons. Happily for superhero comics fans, though, that experimental balloon lifted the industry to new levels of reader involvement.

In the June-July 1961 issue of DC’s The Brave and the Bold (#36), Editor Julius Schwartz involved fans directly, printing names and addresses of letter writers—and including contributor credits (Gardner Fox and Joe Kubert) for the stories in the issue. The curtain hiding information and history was being pulled back.

By the autumn of 1961, DC editors were reaching out even more to nostalgic fans, with “Flash of Two Worlds” combining Silver and Golden Age Flashes in The Flash #123, Showcase #34 introducing the Silver Age version of The Atom, and Marvel joining in, with Fantastic Four #1 (November 1961) kicking off Silver Age versions of Plastic Man, Invisible Girl, and Human Torch. What a year!

Details, details

Mind you, we were still figuring out how to build and care for our collections.

We’d piled our comics in stacks, put them in drawers, whatever. Had we figured out plastic bags at that point? And why were old comics pages turning brown? And was “Magic Tape” really a good idea?

I think we’d figured that one out at the time, actually. And we’ve learned quite a bit more in the last 60 years.

It seems to be a pretty good time for long-time fans and new readers alike to celebrate this 60th Anniversary together.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!