STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 049: Alack Sinner

I’ve been waiting almost 30 years for this book.

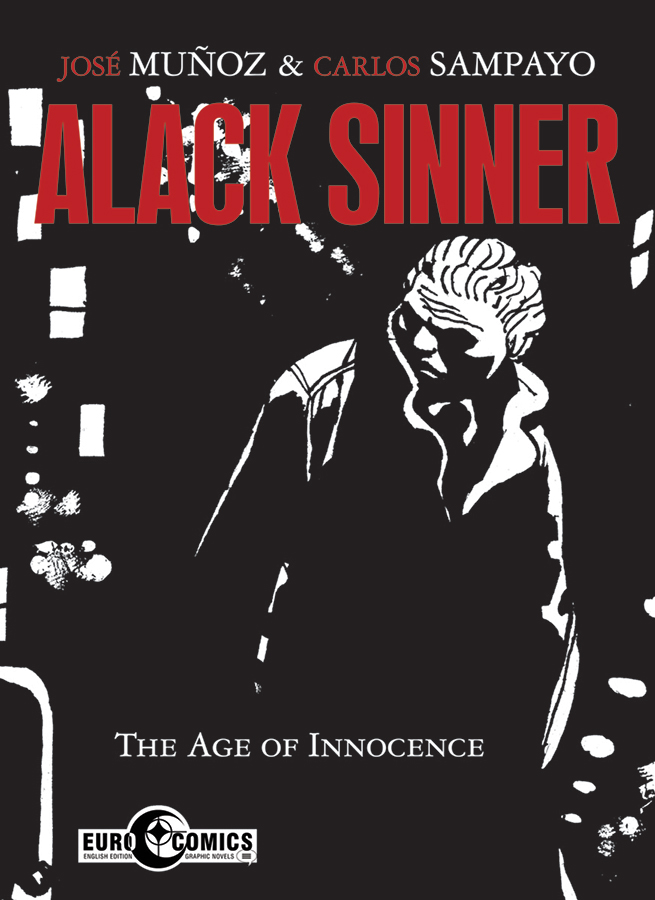

EuroComics, a division of IDW, just released Alack Sinner, a 400-page, black and white collection of expressionist stories drawn by Jose Muñoz and written by Carlos Sampayo. The stories follow the eponymous ex-cop/ private detective/ cab driver Alack Sinner, through a series of cases set in the decaying New York City of the 1970s and early ‘80s.

I’d first read Muñoz & Sampayo’s work when I was in art school in the late ‘80s. NPM published a translated edition of Joe’s Bar, a collection of stories that spun out of Sinner’s milieu. To say they were a revelation is an understatement. I’d never seen comics that communicated such a distinct and compelling worldview so effectively. Over the next few decades, I read and reread the Joe’s Bar stories, and kept an eye out for more of their work in English. There wasn’t much: one graphic novel, a couple of magazines and a few short stories in some anthologies. So you can imagine how thrilled I was to see this handsome new edition from IDW arrive at my local shop.

As far as I know, Muñoz & Sampayo had never visited NYC when they created these stories, which is remarkable to me, because above all else, they feel observed. The stories are full of incidental details and background characters that remind the reader that the story they’re reading is only one of many. Often Sinner and his associates are pushed into the far background of a panel or sequence and we get a glimpse of the life and struggle of some other character.

And “struggle” is definitely what’s going on. The characters in Alack Sinner are oppressed and oppressors, tormented and tormentors. The writer and artist both left Argentina and settled in Europe to avoid the Junta, and their politics inform much of the pain and sadness they depict.

In the first Alack Sinner story, “The Webster Case,” Muñoz’s drawings are solidly academic in the manner of early influences F. Solano Lopez and Hugo Pratt. At the start, his pictures are built from thin outlines and broad areas of solid black with just a few areas of close pen or brushwork to indicate specific textures and create greys. He initially incorporates only a tiny bit of expressive distortion.

But over the course of that story, things start to shift. Pen and brush lines lose their sense of calm control and take on a certain urgency. Features distort. Shadows pool in odd, unexpected places. Supporting characters begin to feel less like extras in a cop show and more like they might have stepped out of photographs by Weegee, or paintings by George Grosz or Amedeo Modigliani.

This process continues throughout the book. With each chapter, Muñoz’s drawings and Sampayo’s stories are less interested in depicting the surface of Sinner’s world, and more concerned with communicating its emotional states and power dynamics. Sinner, his city, and the people who surround him become increasingly vulnerable and disheveled as the stories progress. And the powerful people, the cops, mobsters, plutocrats, and celebrities, all twist into nightmarish icons of corruption.

Munoz is able to depict his figures with sympathy and compassion, but these are stories about people trapped in a brutal world that brings out our worst and most depraved inclinations. Some fight to maintain their decency, their connection to humanity, and that’s where his, and our sympathies lie.

Munoz’s influence can be felt throughout today’s comics, but there’s no other work like this out there. No one else puts so much emotion on the page, or tells stories with this much rage and empathy and pain. I hope you’ll take a look at Alack Sinner, because it’s an absolutely spectacular example of what comics can be.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!