MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 034: It’s EPIC!

I recently became caught up in a conversation with someone who sneered that, while he was a devoted fan of motion pictures, he never watched television. To which I responded that it was in television, not movies, that we most commonly find today’s epics.

All of which led me to consider the epics that the field of comics has given us.

Here’s the thing: It’s a bit tricky to differentiate between what we might term “epics” and what might better be regarded as “soap operas.” I don’t think of the classic newspaper strip Gasoline Alley as an epic; it was the ongoing tale of the ins and outs of family life in America, sure. But. Hmm.

Dick Tracy? Joe Palooka? On Stage? Modesty Blaise? Hey, maybe Prince Valiant …

Let’s think about definitions of “epic,” dimly recalled from my freshman Intro to Lit class at Oberlin. Or, cheating, let’s look at what Wiki has to say. (We’re talking the literary term here, not the Marvel imprint. Just to be clear.) We’re not talking about poetry or an artform limited to formal oral tradition. So, roughly, I’m thinking of a story that resembles an extended, complex tale celebrating heroic feats.

I’m going to toss in one extra qualification: I think it requires a beginning, middle, and end. Arthur, Robin Hood, Odysseus, Aeneas, Beowulf: They wrapped things up with some sort of conclusion. I’ve enjoyed tales of Airboy, Hellboy, Batman, Donald Duck, Fawcett’s Captain Marvel, Concrete, The Spirit—the list, obviously, goes on and on for thousands of comics over many decades. But their stories are largely (whether as single installments or larger story arcs) stand-alone interludes.

Given all that, however, it does seem to me that comics have given us several actual epics. These include:

1977-2004 Cerebus

Dave Sim’s 300-issue masterpiece was a vast project. In the first collection, printed a decade after the series began, he wrote, “Although crude, I hope the dedication of a rookie taking his first tentative steps unburdened by editorial interference still shows through. It was a wonderful time. And my hair was much longer.” What began as a comedic take on swords-and-sorcery fantasy grew over the years into a showcase for his developing skills at art, storytelling, parody, satire, and even such seemingly minor aspects of comic book skills as lettering and mastery of individual dialogue.

1986-1987 Watchmen

Alan Moore wrote a dozen issues, beginning with the premise of what might happen in later years to an assortment of costumed characters who had once hung out together. (Famously, Moore began with a possible evolution of Charlton’s characters but morphed them, instead, into new identities.) Beginning with the concept of aging heroes, Moore and artist Dave Gibbons crafted a combination of heroics and mystery while delving simultaneously into such basics as the tendency of power to corrupt.

1989-1996 Sandman

Though the series began with its feet in the DC Universe, in 75 issues Neil Gaiman called on epic traditions to leap to new worlds of fantasy. While many of the tales of the seven “Endless,” with a focus on Dream (others being Death, Delirium, Desire, Despair, Destiny, and Destruction), were standalone stories or arcs, the series as a whole took readers through one extended adventure. The eternal forces played out their roles in stories that often evoked the dark side of human existence. And of the existence of those forces.

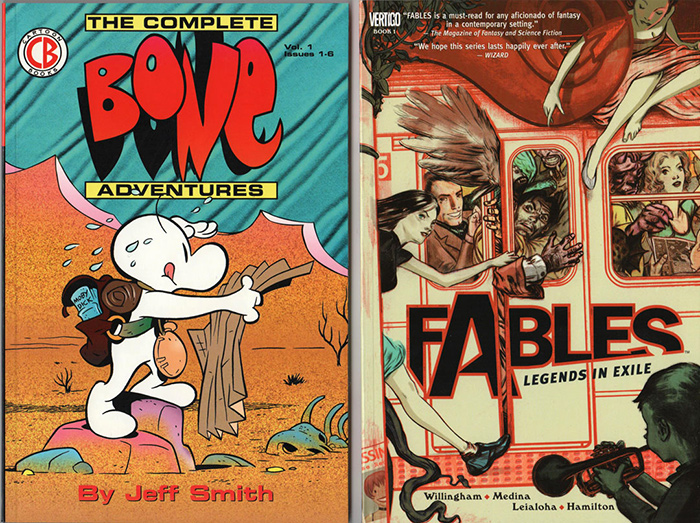

1991-2004 Bone

Jeff Smith’s story began simply enough with several comic creatures caught up in a world of fantasy intrigue. In 55 issues, he told a tale that (Wiki says) Time described, “as sweeping as the Lord of the Rings cycle, but much funnier.” But Smith’s epic had the setting of a complex universe, and he used its humor and its menace in an ongoing counterpoint that provided the story of a struggle against dark forces.

2002-2015 Fables

Bill Willingham’s 150-issue series began by positing that characters known in folk tales for decades—even centuries—live among us in the modern world without our realizing it. And that they have loved and fought and won and lost momentous conflicts during their existence. Given that premise, the possibilities were enticing, when such characters as Jack Horner, Snow White, Bluebeard, and Mowgli lived and interacted in the same universe.

Hmm …

After compiling this list, I realize that each of the epics I’ve picked has had a single writer at its foundation. And I question in retrospect whether (a) DC has been an especially fertile home for structured beginning-middle-end epics or (b) these were simply among the series that first occurred to me. And that, in turn, may be because they’ve been considered classics almost since their respective inceptions, earning a pile of awards over the years.

I realize, too, that I’ve dodged the world of manga in which reside many comics epics.

Moreover, there are other epics I haven’t included (Usagi Yojimbo, Saga, and Groo, I’m looking at you), because they continue, delightfully, to entertain us in ongoing publication. Which is as it should be, because one of the aspects of epics is that they end. And I’m perfectly happy to continue to have the thrill of reading new events in the fictional lives of some of my favorites.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Monday of every month here on Toucan!