MAGGIES WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 089: Looking for Laughs

One of our favorite forms of entertainment has been called “comics” for a long time, emerging from the 1700s usage that meant “funny.”

Standing Alone

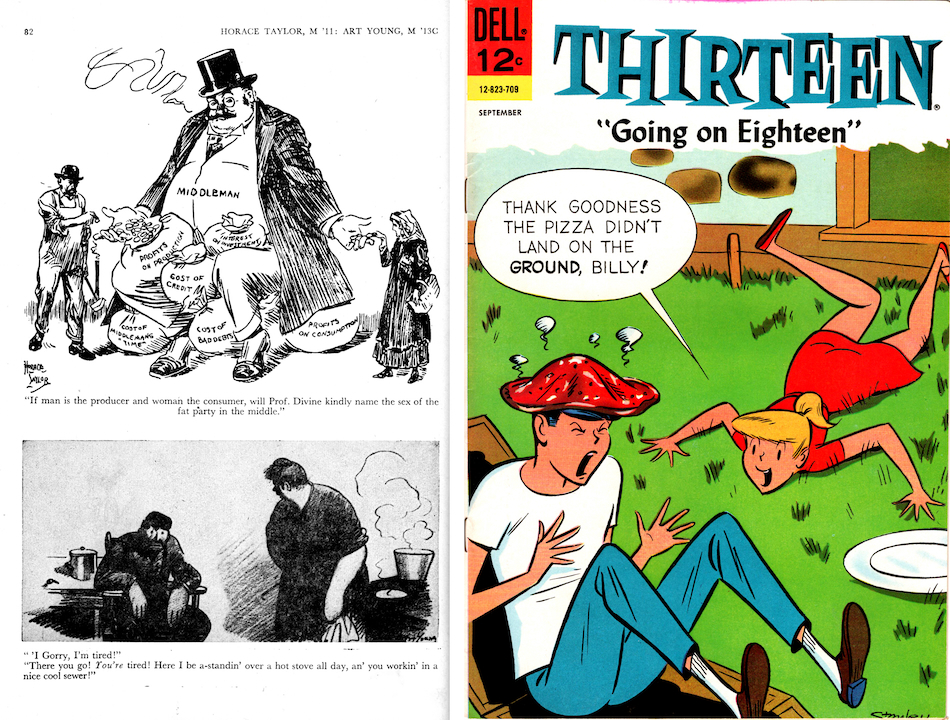

Frequently, as the comics artform developed, one of its most popular—and challenging—formats was the single-panel gag.

It may have survived to greatest effect in stand-alone political cartoons, but such ongoing syndicated panels as Dennis the Menace and The Far Side have, of course, been popular enough to merit book collections over the years.

Among the challenges is that the background of the stand-alone gag often has to be understood without elaboration. Whether the reader sees it as a stereotype or a meme, there’s a commonality to the setup: Do you see a cannibal pot? Two people on a desert island? Or behind bars? Is there a St. Bernard? Someone emerging from Asia via a deep hole? Someone pounding on the wall to complain about noise from another apartment? A thought balloon? You get the idea. (The wonderful collection paying tribute to cartoonist Sam Cobean, The Cartoons of Cobean, featured a combination of these on the jacket: A man and woman stand on a traffic island in the city, surrounded by cars. The man’s wistful thought balloon, as he admires the woman, is of them stranded alone on a desert island.)

Magazines and newspapers featured countless gag cartoons over the decades, and the evolution to ongoing serial adventures of humorous characters really took off with newspaper syndication. Then, newsstand-distributed comic books emerged in the 1930s, initially supplied with content collected from what had been syndicated.

(Note: While a hefty percentage of comic book material was funny, a lot of it was not—and wasn’t intended to be. There quickly emerged discussions in which some griped that “funnybooks aren’t funny,” “comic books aren’t comic,” and the like. But, even as action-adventure became a major genre of comics in newspapers and on magazine racks, gags and imaginative humor still maintained their presence.)

The Golden Age

A look at the evolution of comic book magazines (as opposed to reprint collections of earlier gags in book form) shows that early outings were filled with reprints of what had already appeared in newspapers. Eastman Color’s Famous Funnies #2 (July 1934) was the first second issue of any U.S. comic book, and it had a mix of action and humorous content. New Fun Comics (February 1935) from what would become DC contained original content and included funny animals. Dell kicked off Popular Comics in February 1936, and by the time of comic books dated January 1937 (on sale at the end of 1936), the comic book racks were beginning to fill. Centaur had Detective Picture Stories #2 and Funny Picture Stories #3. David McKay had King Comics #10. DC had More Fun #17, New Book of Comics #1, and New Comics #12. Dell had Funnies #4 and Popular Comics #12. Eastern Color had Famous Funnies #30. And United Features had Tip Top Comics #9. Most of the gag content seemed to come from strip reprints at that point; there weren’t a lot of new laughs.

A decade after the scant pickings dated January 1937, there were a few more titles on the newsstand (about 105). And a number of those were aimed at readers young and old in search of a laugh. Many of those comics were licensed and had fresh material, often created by people working anonymously (Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, New Funnies, Our Gang Comics, Disney titles, and much of the content of Animal Comics, for example).

While the Golden Age was often termed such in retrospect by fans of costumed heroes, it was also a Golden Age of humor. Such creators as Carl Barks, George Carlson, Walt Kelly, and John Stanley produced classics, even when some of them couldn’t sign their names to their work, thanks to licensing restrictions. The humor in early comic books can be generalized as farce. But there are other forms of humor, and a detour into parody even emerged in the Golden Age. Will Eisner’s action-adventure feature The Spirit was often satiric—and some installments even made fun of Will Eisner’s own storytelling. (I call your attention to last month’s Maggie’s World installment.)

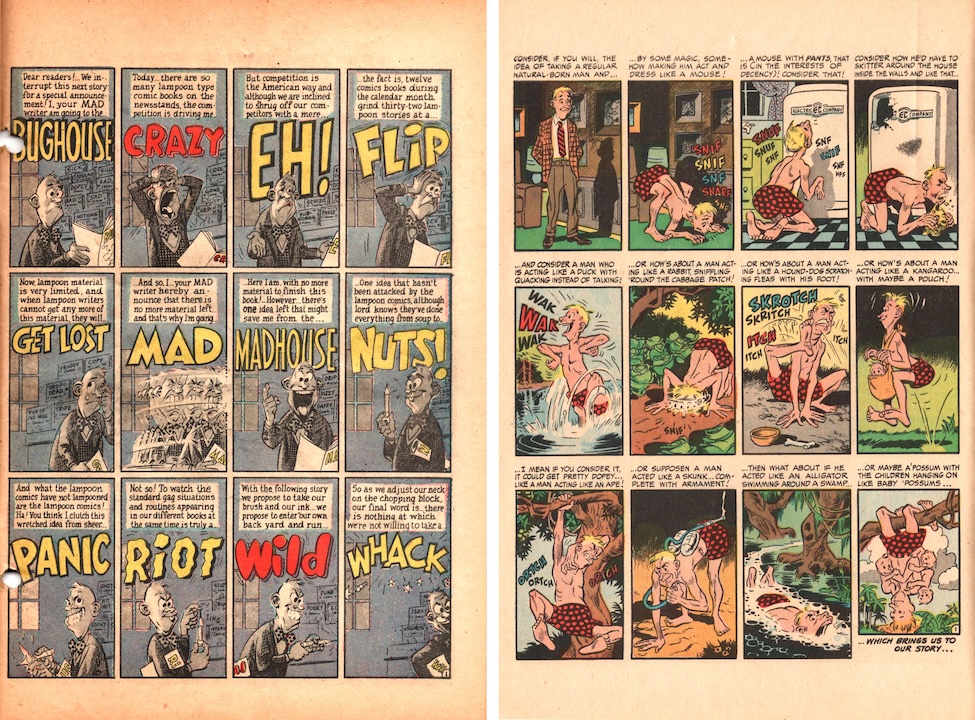

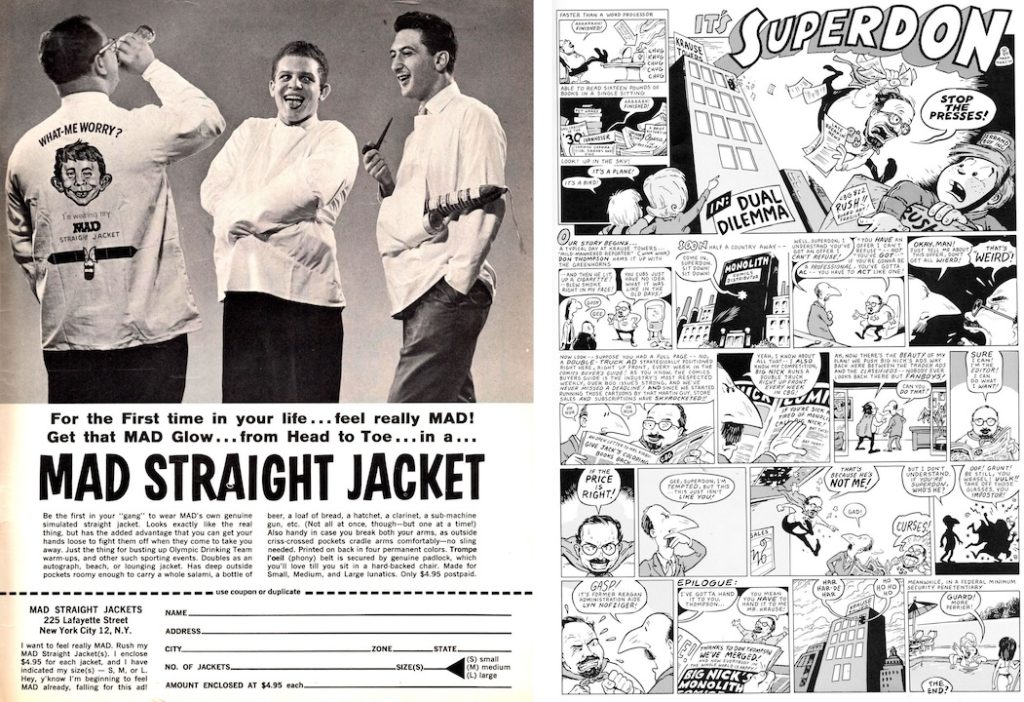

Writer-artist-editor Harvey Kurtzman took such material to the next level in MAD (the first issue dated October-November 1952), mocking horror, crime, and western comics. In less than three years, there were a dozen such series on newsstands. (In fact, one of the earliest comics fan groups comprised people devoted to that sort of publication.)

But, of course, those weren’t the only humorous avenues for gags in comic books. So-called “funny animals” had become commonplace for creators who looked for slapstick at a slight remove from human hilarities. And the humorous comics did well.

Silver Age Silliness

In fact, if the Silver Age is agreed upon as having begun with DC’s Showcase #4 (September-October 1956, featuring The Flash), it’s easy to forget that—whereas many superheroic titles had been languishing until then—the funny comics had been chugging right along. That month’s newsstand series featured more than 50 gag-oriented releases, including Abbott and Costello #40, Archie #82, Casper the Friendly Ghost #48, Dagwood #69, Dennis the Menace #18, Fox and the Crow #35, Fritzi Ritz #46, Katy Keene #30, Leave It to Binky #56, Little Lulu #99, Nancy and Sluggo #136, Sad Sack #62, Three Mouseketeers #4, Tweety and Sylvester #14, Uncle Scrooge #15, and Wilbur #68.

As superheroes began to take increasing space on comics racks, that didn’t mean the fun had left the field.

These Days …

What’s old and funny can be current and funny (or even hit close to home), thanks to reprint accessibility. Moreover, our existing collections on bookshelves and in comics boxes can bring us laughs—and so can delights from current newspapers and comics shops. Even the satire of times past turns out to have things to say about today, including such nods to our field as the behavior of The Simpsons’ Comic Book Guy.

A look at Stephen Becker’s history of comics in Comic Art in America (1959) demonstrated that what was old can be new again. A random page turns up a 1959 George Lichty panel cartoon of Civil Defense Headquarters: “… and it’s gratifying to note that public cooperation in the test evacuation of this city was 100% … They had traffic hopelessly snarled within minutes!”

Yep. And ouch.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!