MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 093: Credit

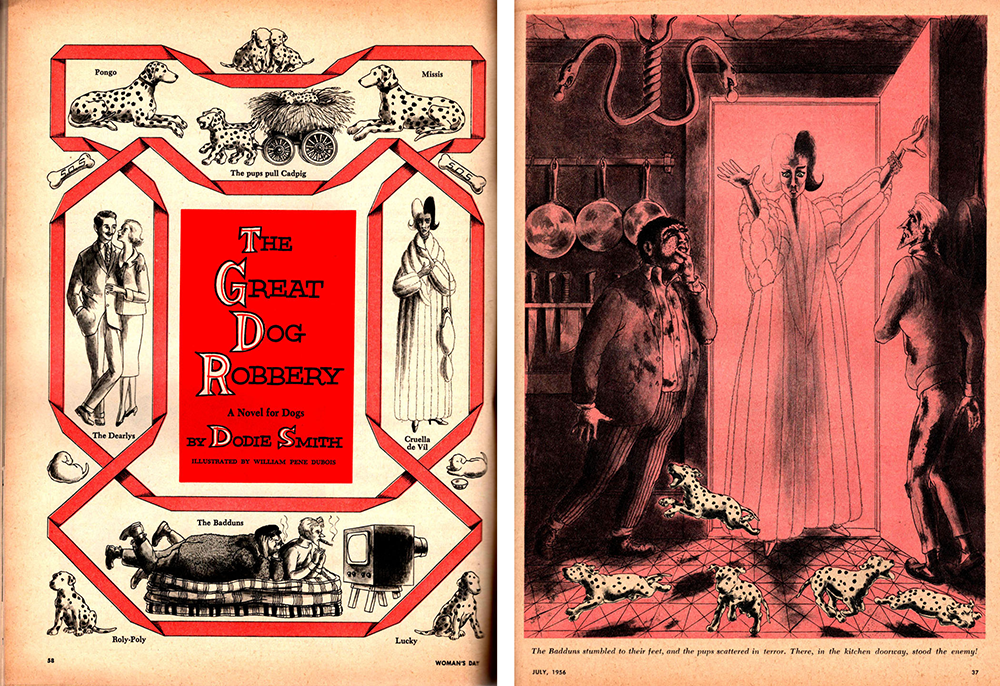

I was 13. Mom used to buy Woman’s Day magazine (7 cents! cheaper than a comic book!) at the grocery store, and at some point I’d read her copy. The June 1956 issue cover-featured Danny Kaye—but there was also a cover notice about a serial starting in the issue: “Part 1 of a new novel: The GREAT DOG ROBBERY.”

I enjoyed the heck out of that first part—and the three that followed. However, when the novel was later published in book form, I noticed that the pictures I’d loved were missing and that the copyright page had this notice: “The Hundred and One Dalmatians appeared in serial form, with different illustrations, as ‘The Great Dog Robbery’ in Woman’s Day.”

What I didn’t know was who that original artist had been or why the art wasn’t in the book.

But when the movie version—One Hundred and One Dalmatians—came out four and a half years later, I realized that the villain’s design was the one I’d seen in the magazine in 1956.

And I’d wondered about the identity of that original artist ever since.

Now …

My curiosity finally demanded satisfaction. I tracked down a copy of that 65-year-old magazine for sale online—and was stunned.

Because, although I’d admired that artist’s work for decades, I’d never seen him credited for this specific pop culture contribution.

William Pène du Bois (May 9, 1916–February 5, 1993) had won the 1948 Newbery Medal (as author of the most distinguished contribution of the year to American literature for children) for The Twenty-One Balloons and was a runner-up for the Caldecott Medal (as artist of the most distinguished American picture book of the year for children) for Bear Party in 1952 and for Lion in 1957. But I don’t think there are many these days who are familiar with the art he had provided for that original four-part serial.

Here’s the description that du Bois had been given: “. . . a tall woman came out onto the front steps. She was wearing a tight-fitting emerald satin dress, several ropes of rubies, and an absolutely simple white mink cloak, which reached to the high heels of her ruby-red shoes. She had a dark skin, black eyes with a tinge of red in them, and a very pointed nose. Her hair was parted severely down the middle, and one half of it was black and the other white—rather unusual.”

That’s it. Her hair could have been braided. Could have been in a bun—or two buns. Could have been in a pixie cut. Could have been in two ponytails. But du Bois chose his own “rather unusual” style: the style that was used—with one change—in the film.

Raggedys

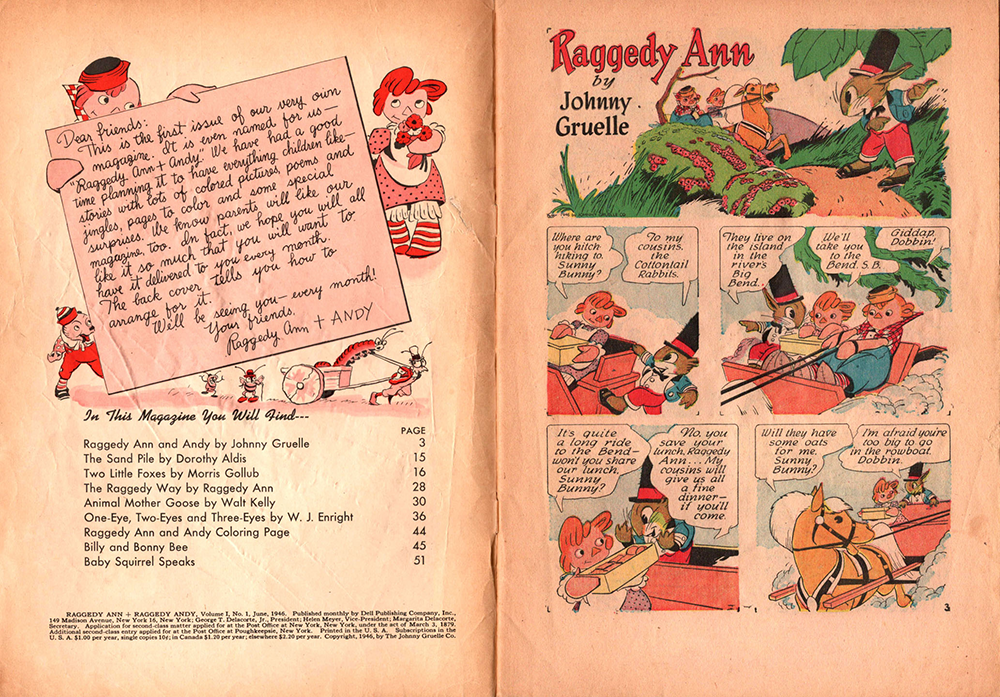

Writer/artist Johnny Gruelle (December 24, 1880–January 9, 1938) introduced Raggedy Ann as an actual doll, which he patented in 1915. Her first book appearance came in his Raggedy Ann Stories in 1918, and Gruelle went on to expand his cast and output.

In comic books, Ann and her brother, Raggedy Andy, were the stars of Dell’s Four Color #5 (1942), which was ©1942 Johnny Gruelle Company. And the copyright was the same for #23 (1943), #45 (1944), and #72 (1945), before they got their own series.

Raggedy Ann + Andy #1 was dated June 1946, and it was an anthology comic book series that included the first installment of Walt Kelly’s “Animal Mother Goose” feature, which Kelly wrote, drew, and signed. Who didn’t sign? The one/s who wrote and drew the story credited to Gruelle, who had died eight years earlier. While that art has been pretty much agreed upon as being the work of George Kerr (March 13, 1870–October 21, 1953)—and, some have suggested, Lea Bing—the scripts of the Raggedys stories have remained uncredited.

Since Gruelle was a cartoonist and children’s books author, my mother (who was supporting my comics obsession at the time) took it for granted in the 1940s that he had written and drawn the comics that bore his name. Over the years, she learned that the stories had been by other creators, and, when she began work in 1982 on an article about those comics, she tried to find out more about them. The Bobbs-Merrill Company was publishing Raggedys material by then, and she wrote to its Character Licensing Division. She outlined what she’d been able to find by that point (most specifically, a 1977 New York Times article) but added that even that “gave me no clues about who were ‘doing’ the ‘Raggedy’ strips in the 1940s, mentioning only ‘by then [mid 1920s] his son, Worth, and a brother, Justin, had joined Gruelle in writing and illustrating the books.’”

The Bobbs-Merrill marketing manager responded that the company needed to know more about her article and the magazine in which it was to appear, adding, “Any material for publication must be submitted for approval to our office prior to publication.” By then, the intended publication was no longer involved with the project, so Mom’s questions remained unanswered then—and now.

Secrets

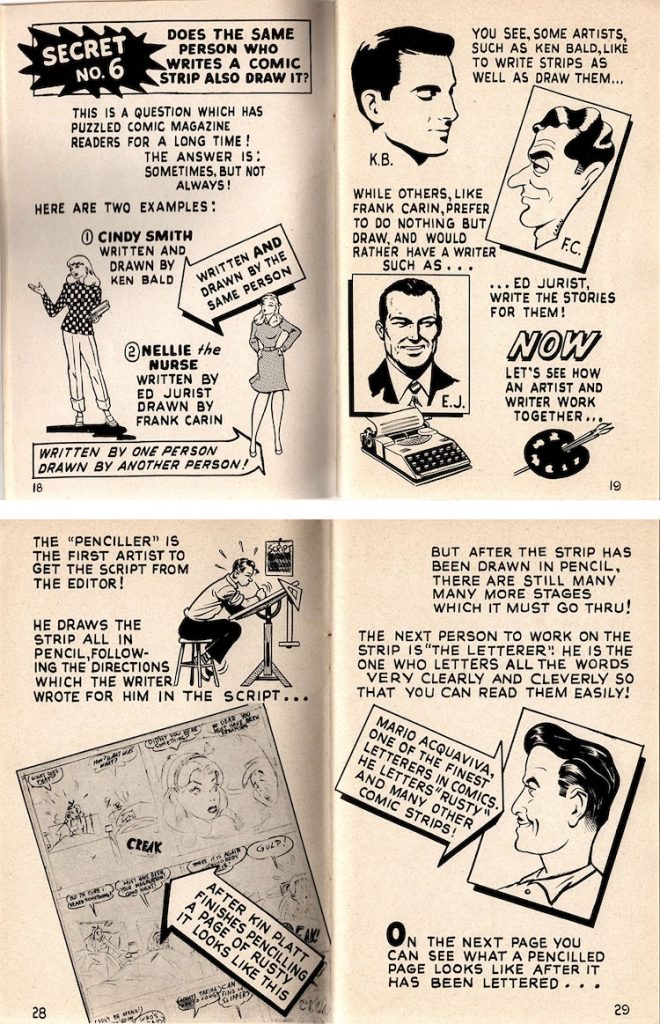

On the other hand, there were a few sources of information about comic book credits for the lucky few who could find them.

Among those was Secrets behind the Comics by Stan Lee, which he produced in 1947. In the course of the booklet, he not only discussed the process of producing comic book content, but he also identified a few of the creators.

On the title page, Stan wrote, “Illustrated by Ken Bald” and “Lettered by M. Acquaviva.” Then, the credits began in the midst of samples: Managing Editor and Timely Comics Inc. Art Director was Stan Lee. Artists discussed (with their work) were Ed Winiarski, Vic Dowd, Frank Carin, Ken Bald, Syd Shores, Morris Weiss, and Basil Wolverton. Specified as pencillers were Kin Platt and Mike Sekowsky—and as an inker, Violet Barclay. Credited writers were Stan Lee, Ken Bald, Ed Jurist, Morris Weiss, and Basil Wolverton. There were entries for letterer Mario Acquaviva, writer and editor Alan Sulman, and publisher Martin Goodman.

On the other hand, according to his files, William Woolfolk (June 25, 1917–July 20, 2003) wrote stories for Marvel’s Blonde Phantom #19, dated only one year after Secrets behind the Comics (in which he hadn’t been one of the creators discussed). But there was no credit for him in that issue—or for any of the other contributors to #19.

So it was that many secrets remained secrets until fans became obsessed with trying to make them public.

By the way …

Did you spot the design change between Cruella in The Great Dog Robbery (1956) and Cruella in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961)? You did—right? Or, putting it another way, the right side! (The du Bois art showed Cruella’s white hair on the same side as her right hand; the films showed it on the same side as her left.)

And now you know a secret behind some comic art, too.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!