JESSE HAMM’S CAROUSEL

Carousel 013: Mapping

Comics are often described as a medium that deals with time. We talk about the pacing of a story, about a story’s moments being ordered chronologically, we describe a title as an ongoing series, and so forth. All of this time-talk is appropriate; comics do diagram the passage of time. But we should remember that comics also diagram space.

Because comics treat us to multiple images, they allow a more thorough portrayal of a character’s surroundings than we would ever find in a single drawing. Through a series of panels, a comic can show us all four walls of a character’s room, plus whatever lurks in his closet, plus the building’s exterior, and more. And if the character goes on a journey, we can follow along, step by step. These revelations turn mere backgrounds into surroundings, creating a sense of the environment that surrounds the character on every side and follows him through his day—a more immersive experience than a single illustration could possibly offer.

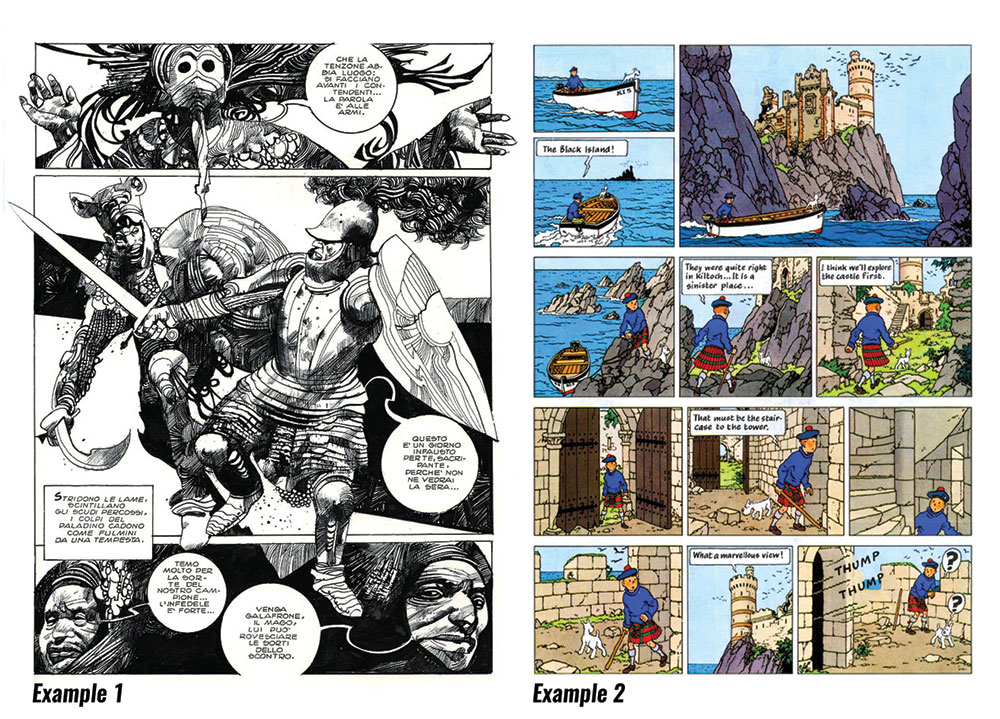

This immersive world-building—or mapping—must be deliberately planned; it doesn’t occur automatically whenever panels are drawn. Consider this page drawn by Sergio Toppi, from Verra Orlando (Example 1). Toppi’s drawing is excellent; his textures are varied, his compositions are balanced and interesting. But you’ll notice on this page that there is no indication of where the characters are in relation to one another, or even what kind of environment they occupy. Are they indoors or outdoors? Is the character in Panel 1 present among the characters in Panel 2? If so, is he behind or in front of them? How far is he from them? The same questions could be asked of the characters in Panel 3. Toppi gives us plenty of information about the characters’ clothing and appearances, but on the matter of where they stand or move, he is silent. The mere fact that we’re offered three panels instead of one tells us nothing about the environment.

Example 2 (Herge) is from the book The Black Island. American Edition ©t 1975 by Little, Brown, and Company.

Now let’s consider a Tintin page by Hergé, from The Black Island (Example 2). Here we see mapping in action. In the first panel, we learn that Tintin and his dog Snowy are on a boat that has just left a strip of land (which can be glimpsed on the left). In Panel 2, we see their destination: a small island on the horizon. Panel 3 reveals a castle on the island, and Tintin’s boat navigating the nearby cliffs. Each panel offers a new piece of information, not only about the story’s events, but about the environment and precisely where Tintin occupies it.

In Panels 4 and 5, we see Tintin and Snowy leave the boat and hike toward the castle. In Panel 6, the pair have reached the castle wall, and a wooden door is visible several yards away. Tintin passes through this same door in Panel 7, and it remains visible behind him in Panel 8. This use of a landmark— the door—to convey the direction and distance of Tintin’s movements is called a hookup. The door’s ongoing presence hooks each panel up to the next, helping us understand Tintin’s movements.

In Panel 8, we see a doorway and the edge of a stair, leading to Tintin’s ascent up a stairwell in Panel 9. In Panel 10, he exits the stairwell, and a merlon is plainly visible on the exterior wall. This merlon hooks up with the long shot in Panel 11, where the merlons along the tower’s upper edge indicate where Tintin is. Hergé has carefully planned this environment and the path Tintin will take through it, and he uses clear drawings, thorough backgrounds, and several hookups to guide us along that route.

Does Hergé’s careful mapping mean that his page is better than Toppi’s? Not necessarily. Comics’ goals are many and varied. A thoroughly mapped environment is one goal you may aim for in a scene, but you may also be concerned with mood, pacing, facial expressions, or other factors which don’t require clear surroundings. Sometimes those goals may even be hindered by an environment; a face in close-up with no background may be ideal. Mapping a clear environment is not a mandate, but a useful option.

And it’s an option too rarely used. It’s much easier to draw characters standing in front of a blank wall, or silhouetted against the sky, with no background details to track from panel to panel. It’s also easier, if you’re willing to include detail, to draw a lot of background detail in one panel and then never portray those details from other angles in subsequent panels, drawing wholly different batches of detail in each. Easier and faster! As a result, few comics portray consistent, convincing environments for readers to mentally occupy. You’d be quite lucky to open a modern comic and see the same background in three or four different panels, from as many different angles, like you often do in Hergé’s comics.

But Hergé didn’t take all that trouble just to waste time. His environments envelope you, and transport you with the characters from place to place, transforming the story from an account into an experience. Even granting that well-mapped environments aren’t always necessary or useful, their presence will generally enrich a story and strengthen its hold on the reader. You’ll have a great advantage in comics if you take the trouble to draw convincing environments, and guide the characters — and the reader — convincingly through them.

See you here next month!

Jesse Hamm’s Carousel appears the second Tuesday of each month here on Toucan!