SO YOU SAY YOU WANT TO WRITE COMIC BOOKS . . .

Devourer of Words 002: Cracking the Codes

“It should be hard. I like that it’s hard… But it should be a little easier.”

—The West Wing, “20 Hours in America, Part II”

Let’s pretend you’ve never written a comic book before—which shouldn’t be hard, since if you gathered all the people who have written comics professionally over the past 20 years, you could probably fill a crappy-college football stadium . . . and no one would have to sit next to anyone. But you really want to try your hand at it. You’ve read a bunch of comics and it seems like it’s not overly difficult. Besides, some of them aren’t very good; you could write a not-very-good comic, too, right? Where should you start?

Start by turning off your computer and go to bed. No pudding for you.

As I mentioned in my first column, comics are an incredibly difficult thing to learn to write—but the first step in doing a thing is having respect for the thing. And if you can’t muster that, step away from the plate.

Comics are hard for two reasons: Form and function.

Form

The next step in doing a thing is knowing what that thing should look like; what form it needs to take to qualify as what you want it to be. If you’re gonna write a prose book, getting a general idea of how that should look is easy. Just open a book. What you write and the finished product are—editing, typesetting and page design notwithstanding—identical. Words, and nothing but words, on a page.

Scripts, on the other hand, don’t get published unless you’re a big honking deal, like Quentin Tarantino or Tony Kushner or Joss Whedon. But, if you want to know what a screenplay or a stageplay or a teleplay looks like, they’re easy enough to find—it’s one of the many things the Internet is for. And, what’s more, they usually follow a very rigid format.

Every professional screenplay you ever read will be written in Courier 12-point. It will have scene headings and transitions. The margins and indents will be identical. Every page of a screenplay roughly equals one minute of screen time. These things are inviolate. So, if you wanted to write a script that, at the very least, looks like the real deal, you’ve got a thing to copy from. (And that also helps if you’re looking to reverse-engineer a movie to its structural parts.)

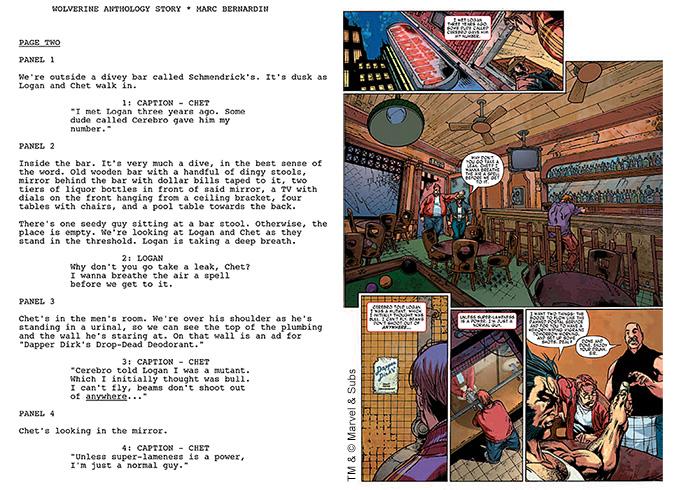

But comics . . . there is no standardized format for comics. Every writer writes their scripts in a slightly different way. Maybe more than slightly. Alan Moore famously delivers his artists these massive tomes to convey his intent (even to regular contributors), while Brian Azzarello’s scripts are almost like telegrams; short and sweet. Poke around in here (The Comic Book Script Archive)* and you’ll see almost as many variations as there are writers; me, my scripts look more like screenplays because that’s the way it makes sense to my eyes.

Regardless of what makes sense to your eyes, here are the things that have to be there: What page you’re on, what panel you’re describing, the dialogue, and any sound effects.

Simple tools, really. But with them, you can tell almost any story. Scratch that: remove the “almost.”

Function

A comic book script is a transitional document. At its most elemental level, it is a series of instructions to the next people in the production line. But in reality it is a statement of intent: It’s how you communicate to everyone else on the project what you’re after.

The editor will help hone the story into its best form, the artist will find new and surprising ways to breathe life into it, the inker and colorist will take cues for mood and atmosphere, the letterer will make the words clear as a bell.

To make sure that your intent survives those many layers of interpretation, it behooves you to be as clear as possible. Don’t swamp your scripts with flowery prose and don’t be overly spare. Tell your story, tell it well, and tell it clearly.

Make it easy for everyone to look good and they’ll make you look good, too.

Are there more things you should know? Absolutely. No more than 28 words, of any kind, per panel—allegedly, Stan Lee figured that out. End every right-hand page with a story question that you won’t get an answer to unless you turn the page. The fewer panels on the page the faster the read and vice versa—you have the power to bend time.

Some of these things you’ll learn by doing, some you’ll learn by reading. But understand the form and the function of a comic book script and you’ll have a foundation to build on.

* The Comic Book Script Archive depends on donations of scripts and funds to keep it going. Please consider helping out if you visit the site.

Marc Bernardin’s Devourer of Words column appears the third Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!