STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 037: Appreciating Jaime Hernandez

© 2016 Jaime Hernandez

I’ve written before about Jaime Hernandez. About a year ago I noted:

“… his razor sharp eye for human behavior, his wit, his restraint, and his ability to use traditional comics tools with new results. He manages to communicate a much wider and deeper range of characters, feelings, images and ideas than most cartoonists. He stripped away my notion of the limits of comics. And it was from reading his work that I learned that you can shift between naturalistic and cartoony without losing the reader’s sense of immersion, that you can get laughs out of juxtaposing something recognizably human with something larger than life, and if you know your characters, you can make them interesting even when they aren’t doing things that advance the plot.”

I think he’s one of the great cartoonists of our time. Love and Rockets, the series he’s shared with his brothers Gilbert and Mario for more than 30 years, just shipped a new issue, and it provides a good opportunity to look at his remarkable cartooning. I’m not interested in reviewing the work so much as looking at the tools he uses.

© 2016 Jaime Hernandez

Jaime’s stories in Love and Rockets—New Stories #8 are: a superhero sci-fi adventure about a new character named Princess Anima, an unnamed story about a high school girl named Tonta and her friends, and “I Guess I Forgot to Stand Pigeon Toed,” a particularly extensive story about Maggie Chascarrillo, Jaime’s longest running character, who dates back to the very beginning of his career. I’m going to focus on Princess Anima.

The Princess Anima story has four chapters: Princess Animus, Isla Guerra, Princess Amnesia, and an untitled epilogue. 22 pages in total. Hernandez drops us into the activity in media res, without any captions, and along the way we’re introduced to 15 brand new characters and a number of unfamiliar settings, all without confusing the reader.

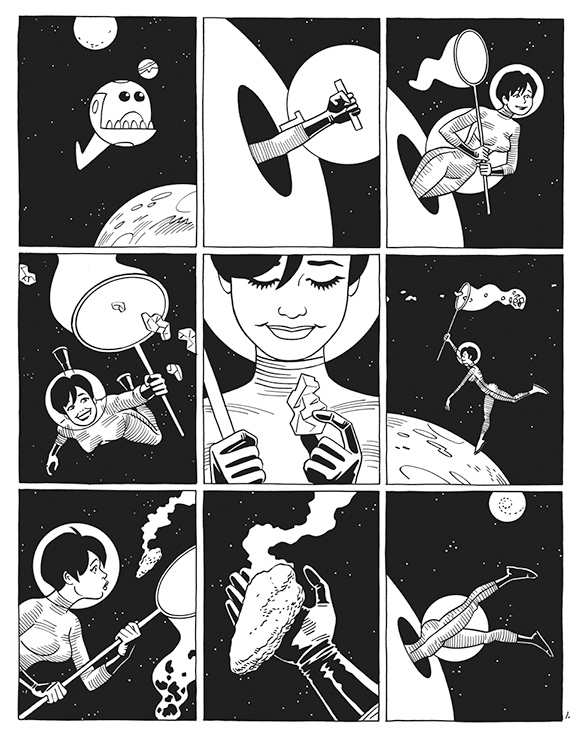

To accomplish this, he’s very efficient about telling the reader everything they need to know. The first panel sets the tone: a shot of a goofy space ship with a face. A hatch in it opens up and the initial focus of the story emerges. She’s an unnamed New Girl on a black market mineral salvage ship, wearing a lightweight wetsuit, doing her job with a butterfly net, capturing various small rocks, including one smoking, fist sized meteorite that gets special emphasis. Had this been a horror story or hard science fiction, Hernandez could have easily drawn realistic space-equipment to emphasize the New Girl’s vulnerability in the dangerous depths of space. Instead, he sets a mood of light adventure with a likable, fun protagonist.

© 2016 Jaime Hernandez

As the New Girl enters, we meet the other two members of her ship’s crew. They’re dressed in campy space-girl pirate uniforms, and their relationship to the new girl is reinforced in every panel. Dialogue lets us know that New Girl’s probably there to replace another crewmate, immediately implying a backstory. Crewmate Trix is immediately and repeatedly hostile to New Girl, and Hernandez starts to demonstrate what New Girl is made of by showing her unfazed by this. Meanwhile, the eye patch-wearing Captain opens the meteorite with a pocketknife and pulls out a tiny unconscious woman.

Over the course of the story, the tiny woman—the Princess—grows to full size and manifests superpowers, seeming alternately friendly and dangerous to the New Girl, who functions as our viewpoint character. Everything that’s a surprise to her is a surprise to us, too.

Graphically, Hernandez restricts himself to an extremely simple palate of black marks on white paper: Figures and forms are mostly described with simple outlines with very little change in line weight. He uses uncomplicated areas of solid black for dark hair, clothing, and the depths of space, and a scattering of carefully placed pen lines to communicate textures and decorative details. Light and shadow are only described when there’s some kind of dramatic light source that’s part of the story. Depth is mostly indicated by overlapping forms, and by their size and placement, never by line-weight.

The layout and camera work is similarly straightforward. The pages are built on a three-tier grid of rectangular panels. No insets or overlapping panels.

Hernandez’s shots are usually at the eye level of the main character, though he sometimes has to move the camera high or low to keep the tiny Princess in the shot. Just about every page has panels that pull the reader back to see the action at full-figure distance. Motion is depicted with well-chosen gestures, plus “swoosh” lines, wiggle lines and the occasional puff of dust, or smoke, or whatever it is comics characters are always kicking up when they run. When action takes place, Hernandez diligently varies both the direction of movement in space and the placement of characters in adjacent frames. (Except for sequences where multiple panels are intentionally staged from a fixed point of view. In those panels, he’s very careful to maintain clarity by not moving things around.)

Most pages have seven or eight panels of roughly similar size. Emphasis is mostly created by framing, or by eliminating other elements, rarely by drawing things bigger. And even with all the panels he draws, and all figures and environments they contain, there is always lots of whitespace on each page. Hernandez is very careful not to tire the eye.

Body language and facial expressions do a lot of the work of characterization. Princess Anima doesn’t even speak a recognizable human language, so her face and gestures are literally all Hernandez has to work with. Fortunately, that’s enough for readers to recognize regret, fear, gratitude, concern, rage, surprise, confusion, determination, delight and more. That’s just on 14 pages, and she’s unconscious for two of them. I hope my readers realize how remarkable that is. I’ve read other adventure comics where characters don’t show that much range in 200 pages.

The fantasy elements are similarly varied. Just across those same 14 pages she appears on, the Princess Anima:

- Is rescued from inside a tiny meteorite.

- Is revealed to be hidden inside the new girl’s spacesuit, drinking blood from her leg.

- Grows suddenly to full human size.

- Becomes ferocious.

- Appears to attack New Girl.

- Is revealed to have actually shielded her from attack.

- Manifests destructive powers.

- Flies away, rescuing the New Girl.

- Struggles to contain her powers and rage.

- Hides with New Girl from their pursuers in a mountain cave.

- Manifests glowing beams from her eyes to help navigate the cave.

- Battles, is swallowed by, and emerges from inside a giant alien monster, which she then devours.

- Flies New Girl to an island where they meet new alien people who speak her unrecognizable language.

- Stands back while the New Girl rescues herself from a sneak attack by one of new aliens.

- Flies the New Girl and the alien off to a port where they might be rescued.

And there’s lots more that happens, too. It’s all framed simply, with most action in the foreground, front and center where it’s easy to see, not obscured by complicated light or details.

Some artists work to create an exciting visual presence by emphasizing daring stylizations of form, or elaborate ink work designed to evoke photographic realism. Hernandez produces clean, unadorned images that are an immaculate combination of classicism and cartooning. And yet they’re most compelling because of the ideas and attitudes they communicate, rather than how they’re drawn. Every panel advances the story, tells us more about the characters and their situation and introduces new elements of conflict or mystery for the characters to engage. It adds up to a story that’s simultaneously dense and breezy, with the giddy energy of a favorite comic from your childhood.

Jaime Hernandez, along with his brother, Gilbert Hernandez, are special guests at WonderCon 2016. Click here for more details.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!