STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 051: Twenty Years Later

Let’s start before I was even aware of the project. Editor Bob Schreck had been talking to Greg Rucka about Whiteout and wanted Greg to take a look at my art and see if I was a good fit for the project. Today, an editor would just send some JPGs or a link to my website or an online portfolio, but this was 1997. Personal websites were pretty rare in comics. I didn’t own a scanner or Photoshop—didn’t even know anyone who did—and I had no clue how to put a picture online. So Bob sent Greg over to my table at a convention to take an anonymous look at my work. Greg liked what he saw, and soon we were working together on the book.

I was a very collaborative artist then, and wanted constant feedback and discussion about every choice. Greg lived an hour and a half away, so if I had a question for Greg about a layout, I’d doodle it on office paper and fax it to him. It was slow and clumsy, but the alternative was driving 90 minutes every time I wanted to show something, so fax was the best option.

The comic takes place entirely in Antarctica. I knew nothing about Antarctica. So Google, right? Wrong. In 1997, Google was still in early Beta. They’d only just registered the domain, and not many people outside of Stanford had heard of it. I spent long hours pecking away at early search engines and portals like Hotbot and Lycos, and they yielded a few useful sites. I’m pretty sure I downloaded and printed every publicly available photo the 1997 Internet had of Antarctic buildings and equipment. After that, I hit the local libraries and bookstores and found every book and magazine article about Antarctica I could get my hands on.

Sometimes I had questions about specific details. Today I’d ask on social media and get an answer almost immediately. Back then, there was no Twitter or Facebook, so I’d find strangers on the Internet who had been in Antarctica, and ask them all the same questions in the hope that one would take the time to answer. Sometimes they did! “Hi; You don’t know me, but I see you were stationed at McMurdo Base last year. I’m a comics artist drawing a story set there, and I know this is a weird question, but do they have single-serving cartons of milk in the cafeteria?” “No. First, it’s called the galley, not the cafeteria. Second, the nearest cow is thousands of miles away. They serve powdered milk in big metal urns.”

In the nineties, my process was all analog. If I wanted a mark to appear in the book, I had to get that mark onto a single sheet of bristol paper with all of the other marks. Here was my process:

1. Rough out tiny thumbnail layouts with a graphite pencil.

2. Measure out a 10 x 15″ box on a page of Strathmore bristol and rule the panel borders onto my page with a pencil.

3. Use a T-square and an Ames Lettering Guide to rule guidelines, pencil in the captions and dialogue, then ink all the letters, adjusting as I went to make everything fit reasonably smoothly. This was usually the first hour or two of every day.

4. Rule panel borders and word balloons in ink using a ruler, a Rapidograph pen, and an oddball selection of ellipse templates.

5. Start penciling figures and backgrounds. I almost never used any direct photo reference in those days. I’d use photos to find out what something looked like, but I’d almost never draw anything from the same angle as a photo. This slowed me down a LOT. If I made a mistake, I’d erase and redraw. If something was particularly tricky, I might draw it on a separate sheet of paper, and use a lightbox to trace it onto my final sheet of bristol, rather than wreck the surface by erasing it over and over.

6. Once the pencil drawings looked good enough, I’d Ink them with a Winsor-Newton brush, crowquill pen and India ink.

7. Add reproducible greytones with bootleg zip-a-tone that I made at a copy shop by photocopying a screen-tone pattern onto blank sheets of crack-and-peel sticky-backed plastic. Each section of tone was cut separately with an X-acto knife.

7. Make corrections and add snow effects with thick white gouache. I’d brush it on with an old watercolor brush, or spatter it on with a toothbrush. I’d also scratch at the paper with a razor blade, smudge it with a wax crayon, and do anything else I could think of to make my panels look like they were taking place in the coldest, windiest, driest place on earth.

8. If I needed to repeat a panel, I’d walk a mile to the nearest photocopier, copy what I needed, cut it out, and paste it down on the page with glue stick.

9. Lettering corrections would be a huge pain and require a lot of careful pasting over or whiting out.

Today, I shoot lots of photo reference and draw everything on my Cintiq with Clip Studio Paint. If a panel has tiny details, I just make it bigger. If I draw a head too big, I shrink it. I can add tone or fill in areas of black with a single click. I can try out lines on separate layers, then flatten them onto the final inks if I like them, or delete them with one click if I don’t. I can even make random spatter patterns with a digital toothbrush. It took me a while to find the right combination of tools and settings to make things look the way I want, but now only experienced art professionals can look at a page of my comics and tell whether it’s is analog or digital. Many can’t tell at all.

Back then I’d send my publisher a big stack of pages by FedEx and hope they arrived safely. Now there are no physical pages so I just send a download link to a file.

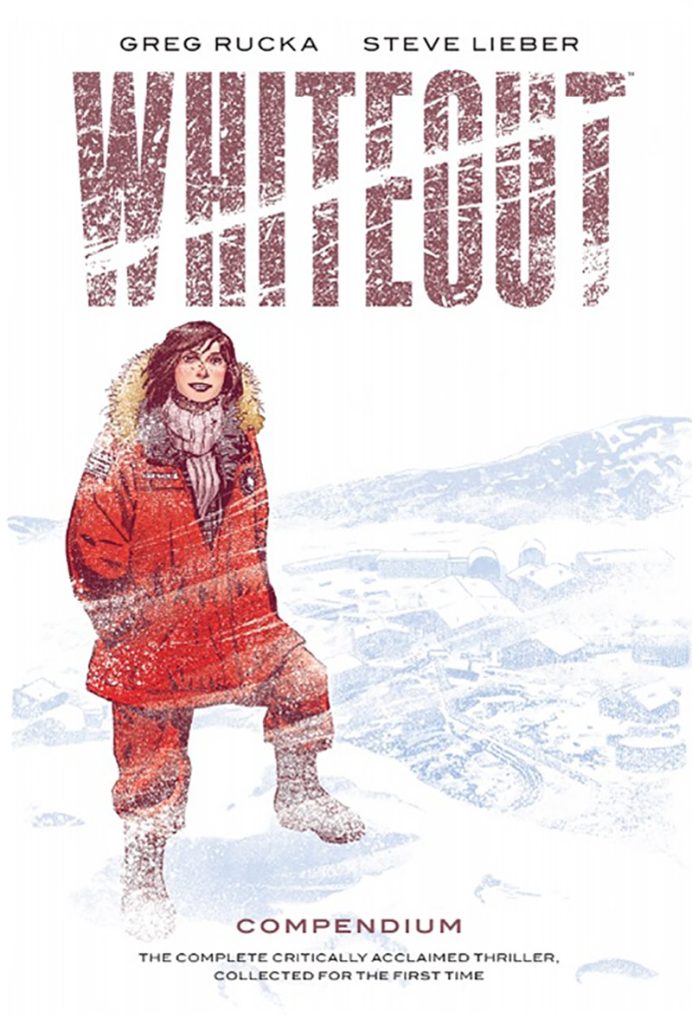

I enjoyed the process of drawing with physical tools. I liked the results and I really miss having a physical piece of original art to sell. What I don’t miss are the many, many hours all those extra steps took, and the physical and emotional stress that came with them. A single error with the brush might mean an extra hour of work. I think I’m a better artist now, and faster, too. But I’m still tremendously proud of the work I did twenty years ago using mostly the same tools that my teachers used when they started their careers around World War II. You can judge the results for yourself. The Whiteout Compendium will be in stores December 6th. I hope you’ll take a look!

How have the ways you work changed since you started making comics? Let me know on Twitter at @steve_lieber, or on Facebook at steve.lieber.

Steve Lieber’s Dilettante will return to Toucan on Tuesday, January 9th!