MAGGIE’S WORLD

Maggie’s World 014: Exploring the Comics World

The comic books that I read as I was growing up were drawn and written in the United States. But my parents had a subscription to Punch, and I soon became a fan of such British cartoonists as Roland Emett (1906-1990), Ronald Searle (1920-2011), and Norman Thelwell (1923-2004). I didn’t know much else about them in the 1950s—or much at all about other comic art that didn’t originate in North America.

As Don and I began to explore together the universe of comics in the early 1960s, we quickly realized how much we didn’t yet know, and that went double for non-U.S. material. Then, correspondence with science fiction fan Alan Dodd (1934-2001) of Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, brought us an influx of clipped British comic strips. We quickly became admirers of what we saw of such strips as Flook by “Trog” [Wally Fawkes (1924-) and the strip’s writers, including George Melly and Barry Took], Four D. Jones by Peter Maddocks (1928-), Garth by John Allard (ca. 1942-), Clive by Angus McGill and Dominic Poelsma, Perishers by Maurice Dodd (1922-2005) and Dennis Collins (?-1990), and Gun Law by Harry Bishop (1922-).

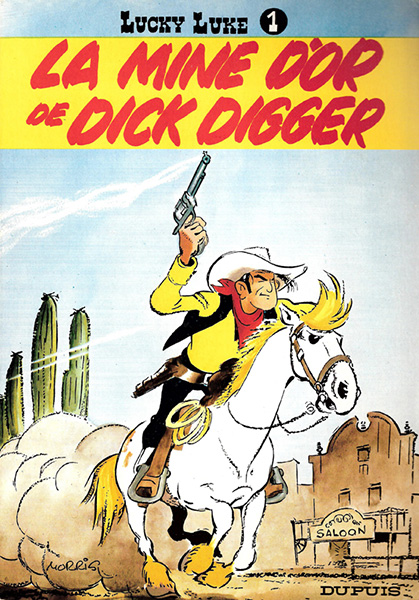

© 2014 Lucky Luke • Dupuis • Darguad

As we increased our involvement with comics, kind folks began to send us even more samples of What Was Out There. Spirou Album #100 (1966) brought us bound and trimmed copies of that publication, introducing us to (among others) Les Schtroumpfs by Pierre “Peyo” Culliford (1928-1992) and Lucky Luke by Maurice “Morris” De Bevere (1923-2001) and René Goscinny (1926-1977). Somehow, we also acquired comics by Mexico’s “Rius” (Eduardo del Rio, 1934-), whose illustrated non-fiction preceded the work of Larry Gonick.

And that was only the start. As comics fans’ communications intensified, contacts became more international. Those Spirou copies contained appreciations of other countries’ classic comics features, and amateur publishers around the world increasingly reached out to each other. The comics amateur publishing association CAPA-alpha had members in Australia, and international correspondence became increasingly common.

© 2014 VIZ Media, Inc.

In 1971, Kosei Ono (then with NHK in Tokyo, now a noted researcher and critic of film, comics, and animation) sent us copies of the monthly COM, which he described as “a new wave comics magazine,” and provided a brief explanation of the features therein. The magazine included installments of the Phoenix epic by Osamu Tezuka, and it was in looking through COM that it probably first struck us just how different comics were in a country in which comic books hadn’t been primarily designed for “family” reading. At the same time, Kosei Ono told of his difficulties as he tried to find U.S. comics in Japan in the early 1970s. While he could locate mainstream DC and Marvel comics, anything out of the ordinary (such as the magazine-format Spectacular Spider-Man and such oddball output as Wally Wood’s Witzend) didn’t make the trip across the Pacific.

And mainstream U.S. publishers began to release comics from other countries. Tintin by Hergé (Georges Remi, 1907-1983) was translated and on sale in bookstores. By 1977, American newsstands were stocking Heavy Metal, the U.S. version of Métal Hurlant that contained translations of the European material.

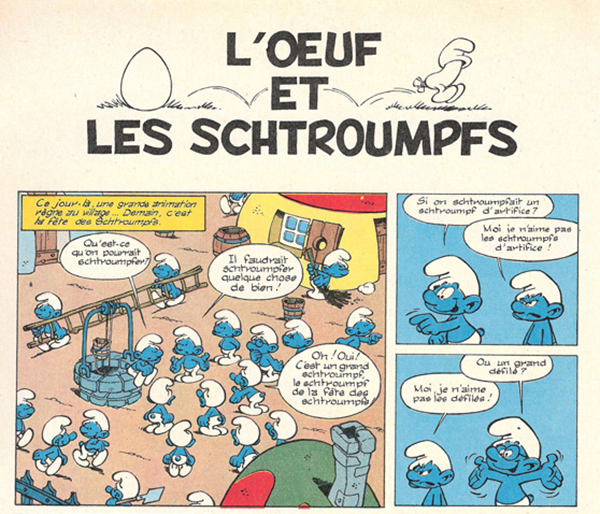

© 2014 Peyo

And such importing continued. I still recall the day I walked into a gift shop decades ago and was surprised to find a display of a variety of the little blue plastic characters I immediately recognized as Schtroumpfs. They, too, had immigrated and, as some other immigrants have done, had changed their name. They were now Smurfs—and they were wildly popular with American kids.

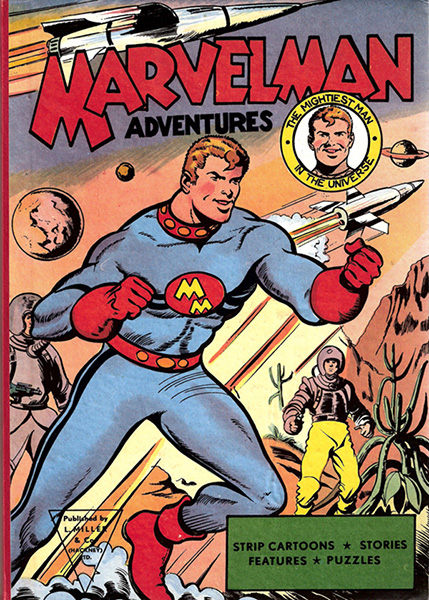

In the 1970s, Alan Dodd had sent us British comics containing the adventures of Marvelman. In 1983, Don and I were in a Wisconsin comics shop, and I picked up a British import that had reached that shop months after its original publication. I paged through Warrior #1 and skimmed “A Dream of Flying” by Alan Moore and Garry Leach, coming to a stunned halt when I came to the closing panel. We bought it, and I still recall the eager anticipation I felt, insisting that Don sit down to savor it.

© 2014 Marvel Characters, Inc.

Years went by, Marvelman became Miracleman—and, though he’s still known as Miracleman, he’s become a sort of Marvelman again: available anew for a new generation. In fact, just look at us now! A glance through Previews and comics shop racks show how our world has widened. Tintin and Smurfs adventures remain in print today, and many different publishers bring U.S. audiences a variety of international treasures. Dark Horse’s line of manga, for example, provides a diverse output. And there’s more, more, more from such hosts as Fantagraphics, NBM, and IDW, to name only a few of the major participants. In fact, the Previews catalog has become “must” reading more than ever, with new entertainment listings every month. Comics for kids? There’s an incredible variety of international comics series, both classic and new, for young readers, including Asterix by René Goscinny, Chi’s Sweet Home by Konami Kanata, Moomin by Tove and Lars Jansson, and Tintin by Hergé, to name only a few.

A walk through the aisles at Comic-Con will soon introduce me to more, more, more. (Note to myself: The more readers buy, the more motivation publishers will have to locate and circulate other entertaining comics from other countries.) I can hardly wait.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!