MAGGIE’S WORLD

Maggie’s World 015: Girls Allowed

Even seven decades ago, comic books were a storytelling art form like other storytelling art forms. Comic books encouraged the girls in their readership to imagine themselves as adventurers, as buddies, as friends with goals just as diverse as the goals of any kid.

In the 1940s, mind you, comic books were all over the place. We think of the published art form these days as finding its primary home sequestered in conventions and specialty shops. But the comic books in the 1940s could be found almost everywhere. Mom walked into a grocery store with her kids? She might go for the dairy section; the kids headed for the comics rack. Dad dropped by the newsstand after church on Sunday? The kids picked through what was new on the spinner rack. Family headed on vacation? The train station and the bus station each displayed an extensive variety of four-color tales for a dime each. Parents shopped in department stores? Yep. Comics were there, too.

So kids read comics—and comics were made for kids. Not just for kids, let me hasten to add. There was a little something to appeal to almost every different reader, especially because many of the earliest comic books reprinted comic strips that had originally appeared in newspapers aimed at all-ages readerships.

When Cupples & Leon, Saalfield, and other publishers produced the early “pre-comic-book” comic books, those comics were collections of strips and panel cartoons families had already become used to seeing in their newspapers: features such as Bringing up Father, Little Orphan Annie, and Tillie the Toiler. And comic books continued the tradition, as they evolved from such anthology series as 1934’s Famous Funnies and 1936’s The Funnies.

Throughout those early days and into series developed especially for the new format, target audiences included women and girls. That is to say that women and girls have been featured in comics since long before I began to read them. Sometimes, they were the viewpoint characters; sometimes they seemed to be there only to be viewed. Because lots of people—young and old, boys and girls, men and women—have read comics for decades and decades and decades.

Sometimes, when targeted readers were girls, there was a super-emphasis on their clothes and hair; sometimes, characters were occasionally featured as paper dolls. Edgar Martin’s Sunday page Boots feature included a paper doll; not only was Bill Woggon’s Katy Keene dressed in her readers’ designs, some of those young designers also grew up to be professional fashion designers. Even before I was born (and I’m now 71), Wonder Woman was deliberately introduced to be an icon of female super-power.

When a reporter for The Washington Times contacted me in preparation for a recent article about where women find themselves in today’s world of comics fans, it got me thinking about the topic in general and recalling the recurring Little Lulu theme of the boys’ club. It was a small shanty with the clear message above the door: “No girls allowed!” And it was the very ridiculous nature of the message that made it such a challenge in story after story. Because, when I was first reading comic books, almost all kids read comic books. Because they were everywhere. In fact, it was my mother who was probably my primary instigator in collecting comics, as she enjoyed reading the comics Walt Kelly was writing and drawing in the late 1940s, and she and Dad began a delicious correspondence with the cartoonist.

Four Color #158 (also known as Little Lulu #9) © 1947 Marjorie Henderson Buell

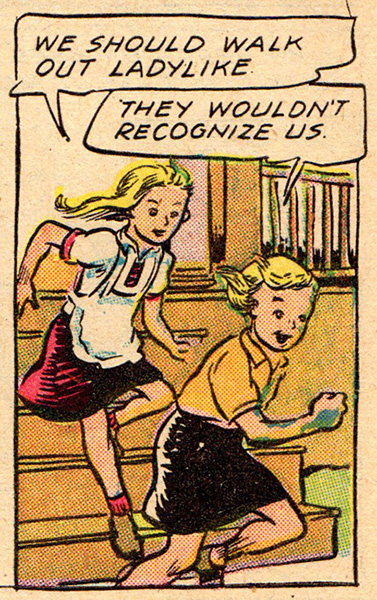

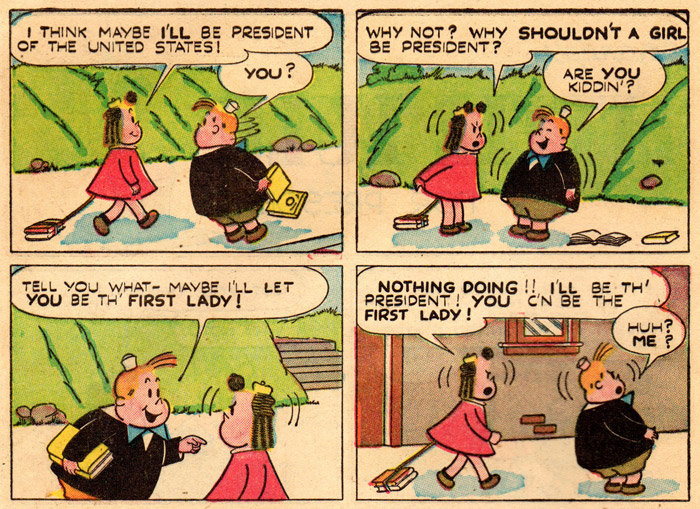

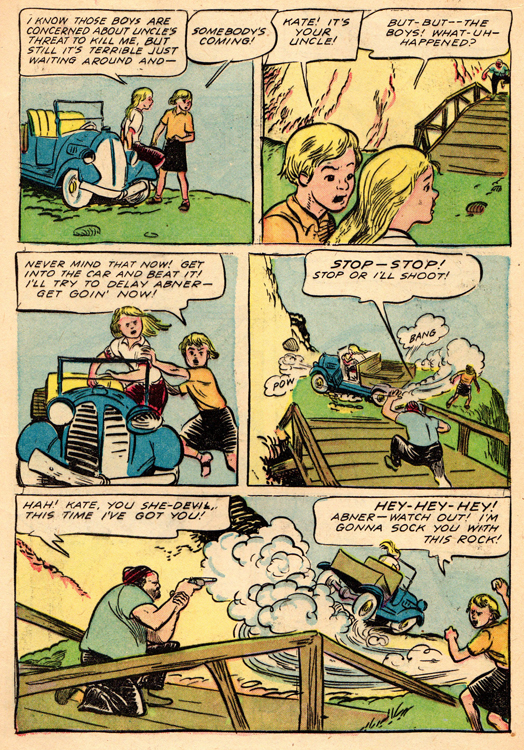

While that was happening, what did I like? I read a variety of comics when I was little, but my favorites tended to be those created by the talent assembled by Dell’s editor Oskar Lebeck, who brought me Raggedy Ann + Andy, Little Lulu, and more. The stories created under his leadership seemed deliberately crafted to be entertaining, no matter the gender of the reader. Nor was gender a determiner of who created such comics. Marjorie Henderson Buell created Little Lulu, but it was John Stanley who had Lulu tell a generation of girls they could be president someday. Our Gang’s last movie short appeared in theaters in 1944, but it was Walt Kelly who turned Janet into a powerhouse of action, an equal of the boys in adventures as well as comedy. (It was in 1945, in Our Gang #19, that she donned slacks and had little Two by Two cut her hair so they could be go on adventures.)

Detective girl, funny girl, dumb girl, smart girl, sexy girl, active girl, passive girl, little girl, “Good Girl”—and, yes, little-kid girl and adult girl (also known as woman, but what the heck?)—there were comics with all of them, year after year, era after era.

Over the years, characters and series morphed, of course. Archie was the focus of his early adventures, and Betty and Veronica were, in at least some part, simply there as eye candy and prizes to be fought over. Over the years, too, comics became harder and harder to find. Comics racks were no longer omnipresent, many girls’ incomes went increasingly for such non-parentally provided expenses as cosmetics and hairstyles, and it became more socially acceptable for boys to hang around the increasingly limited venues where comics were to be found. Comic books for girls weren’t as easy to find where their buyers might be shopping.

By the time the Silver Age was in its early days, Jean Grey was initially “Marvel Girl,” just as Sue Storm was initially “Invisible Girl”—and both seemed to appear more as decorations than as valuable team members. And so the 1960s continued.

The first multi-day New York City comics convention occurred in 1966. Four females attended: Pat Lupoff, Lee Hoffman, Flo Steinberg, and me. When a reporter asked me in February 2014 how many girls and women attended comics conventions these days, I sent her the link to Comic-Con’s website pages of photos of the 2013 event and commented that there were clearly more than four.

Because, as with virtually all other factors you can analyze about comics, there are all kinds of female comics characters for all kinds of reader. And readers can even re-imagine what has gone before—or, if they become creators, can change the characters themselves.

(When Don was reading early issues of Fantastic Four to daughter Valerie in the early 1970s, he made his own changes to the story. Figuring his daughter needed a different role model than someone whose power was pretty much limited to hiding, his narratives put Reed Richards’ lines into Sue’s mouth, making Sue the clear brains of The Fantastic Four. Just saying.) Recent decades have seen formats such as manga and series such as Sandman that continue to draw in more and more readers of both genders. These days, animated cartoons such as Frozen and Brave feature problem-solving, gutsy gals having exciting adventures, and young audiences seem to be getting a kick out of them. (Speaking of animation, what viewers don’t realize that it’s Lisa Simpson who’s the brains of that family? Or do I digress?)

It doesn’t mean there are no issues of employment, character design, role models, strange costuming, or other topics open for discussion in today’s comics. But it does mean that girls are allowed. And, hey, so are boys. And men and women. And toddlers dressed in costumes. There are even T-shirt designers featuring comics logos on women’s styles.

Spread the word: Comics are for everyone—and, yes, have always been.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!