MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 027: That’s The Spirit!

“It’s very hard to trace back to the first influence I had as a cartoonist,” Jules Feiffer wrote in the March 1961 issue of Playboy, “but I think the most important in the early years—for me and a number of other cartoonists—was a guy named Will Eisner, who did a strip called The Spirit. I dare say Harvey Kurtzman would not have come up with Mad magazine if Eisner hadn’t preceded with The Spirit. The way my thinking developed, and where it finally went, in the beginning, was very largely because of Eisner.” Don and I quoted his comment in the first issue of our Comic Art (spring 1961).

In our second issue (published in early autumn that year), others responded to the quote. Artist Steve Stiles wrote in response to receipt of that first issue, “Thanks for Comic Art, I’m glad to see something like this spring up—I’ve always wanted to have EC and The Spirit, my two favorites, crowed over. And please, please discuss them—they’re really worth going ‘Rah, rah, rah!’ about.” And “Feiffer was quite right in saying that without Eisner there would be no Mad. Even without the normal sense of humor which prevailed in The Spirit, Will always indulged in lampooning things, imitating magazines, inserting photos, running fake ads. Eisner also heavily influenced the serious EC line.”

In response, Don wrote, “I plan to discuss Spirit and EC and agree that both should be raved over. For comments on Eisner’s influence on Mad, see the next letter.”

Which was from then-Help! (and earlier Mad) creator and editor Harvey Kurtzman:

“Comment on Feiffer’s statement: There would have been just as much of a Mad without Eisner as there would have been [Feiffer’s cartoon collection] Sick Sick Sick without my Hey Look.

“I think Jules’ statement was well intentioned but neurotic. But Jules is O.K.

“Incidentally, I’m getting some Spirits to run in the upcoming Help!”

Back in the Day

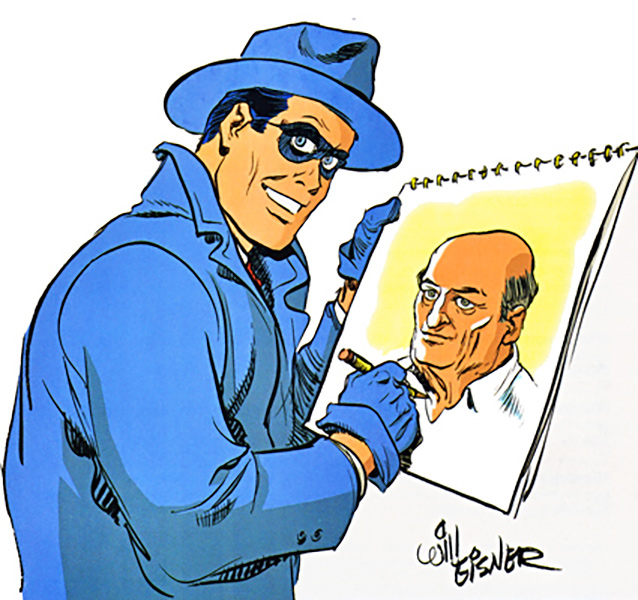

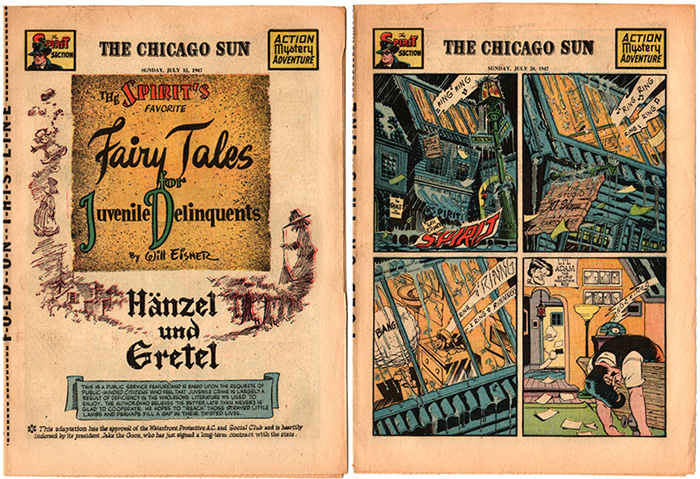

In those early days of comics fan and pro interchanges, there were two varieties of Eisner fans: readers who had seen his ground-breaking Spirit sections as they were being published, and readers who heard about them later and were trying to find more. After all, week after week, the syndicated newspaper inserts had told stand-alone stories—beginning, middle, and end—in just seven pages. And many of those stories demonstrated with incredible variety the creator’s yen to do more and more with the art form.

Will was not just an incredible creative force on his own, but also someone who studied the job to do it better and who learned from his studies.

In 1965, Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes concluded his pioneering collection of essays and stories with a 1941 Spirit adventure. He had concluded his earlier text chapter on Will with the comment, “I collected Eisners and studied them fastidiously. And I wasn’t the only one. Alone among comic book men, Eisner was a cartoonist other cartoonists swiped from.”

His book ignited a fervor of collecting and appreciation that eventually produced too many articles to count—and a vast variety of books with Eisner and his work as the focus. In terms of reprints based on the Register and Tribune Syndicate’s 645 inserted “Spirit section” comic books destined for participating newspapers from June 2, 1940 to October 10, 1952, some of the longest-running came from:

- Quality: 1944-Aug. 50 (22 issues)

- Warren: Apr. 74-Oct. 76 (16 issues)

- Kitchen Sink: Oct. 83-Jan. 92 (87 issues)

Underground comix publisher Denis Kitchen intrigued Will, who was fascinated by the emergence of those comix as a new business model. Will always seemed to want to know more about the business, as well as the creation, of comic books. In fact, even before newspapers lost their Spirit inserts, Will had already diversified into other fields. While he was still overseeing those inserts, he had successfully marketed to the Army the concept of comics as educational tools. His first issue of P.S. described itself as “the magazine of maintenance for trucks and tanks, the nuts-and-bolts digest for anything on wheels or tracks,” and his hand was clearly fundamentally involved in that project, while the Spirit episodes also released that month seemed equally clearly to be the product of his talented staffers.

Under the Influence

When Don and I canvassed comic-book professionals in 1993, we asked participants in the resultant Comic-Book Superstars to list the biggest creative influences on their work. The biggest influence, they responded, had been Jack Kirby. (Keep in mind that Kirby had been one of the most dynamic creators of the Golden and Silver Ages, and by the 1990s comics pros were all well acquainted with his work.) The second biggest was Will. To top it off, as noted, Will, too, was curious about the production of comics and how others went about it. In fact, he spent considerable time and effort interviewing other creators to find out how they did it and share memories of how they had gone about their work.

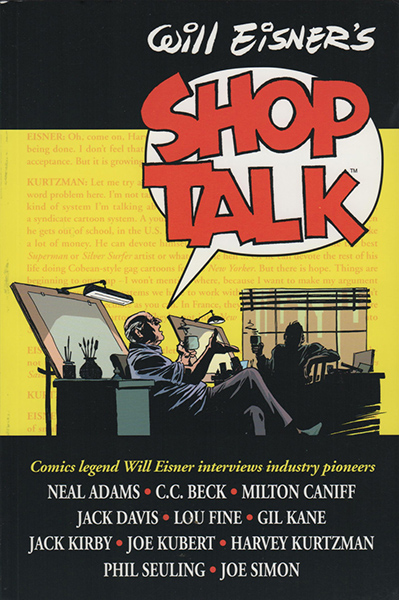

In fact, among Will’s contributions to comics, it was he who’d hired Kirby to work on comics in the late 1930s. As Kirby later told Will, “I always felt you were the kind of guy I could learn from.” That comment appeared in Will Eisner’s Shop Talk (Dark Horse, 2001), a collection of his interviews with fellow creators, and in a chapter on one of his early employees he offered an insight on how he’d handled producing comic books in those early years:

“Sometime between 1937 and 1938 we at Eisner & Iger hired a young artist named Lou Fine. I don’t remember who brought him into the shop. We often advertised for artist-illustrators. There were not many career comic book people floating around in those days, because the field was so new. Therefore, most recruiting was done from the related fields such as the pulps, or book and magazine illustration. In fact, a lot of the recruits came from the fine art field—people like Alex Blum and Martin DeMuth.”

That, then, is one of the earliest activities of his influential career: He developed the fine art of putting together a team whose creative members worked smoothly together to meet its deadlines. Among members of that team over the years were such contributors as Jules Feiffer, Wally Wood, Bob Powell, Jerry Grandenetti, and Klaus Nordling. As Will’s career progressed, it became multi-faceted, from P.S. to mass-market, stand-alone paperbacks to later stand-alones (including adaptations of classic fiction to comics form approaching that challenge decades after Classics Illustrated) to what amounted to actual instruction manuals, based on interviews (Eisner/Miller and Will Eisner’s Shop Talk). Through it all, he learned and adapted.

Information Exchanges

And then there were the fans. Even from our first contacts with him via the Postal Service, Will provided ongoing input. It wasn’t until some time after my article on him had appeared in The Comic-Book Book that we first met in person. Come to think of it, I believe that occurred at a Chicago Comic-Con that was also attended by Eisner Studio member Andre LeBlanc. That may have been the first time many fans became aware of how many creators they didn’t know had worked with Will.

These days, his cooperation with his admirers may be best known via the Eisner Awards. They were begun in 1988, and Comic-Con took over administration of the awards in 1991. Among countless memories of those days is that of Will’s waylaying us at a Capital City trade show to brainstorm the possibility of setting up an additional annual award, one that would recognize the people who sell comic books. Didn’t we think that such an award should be added to the celebration of creative professionals? The Spirit of Comics Retailer Award was announced beginning in 1993, and it was because Will was never satisfied with the status quo, if the situation could be improved. As noted on the Comic-Con website, “He wanted to stress the crucial bond between creators, publishers and retailers in getting the books into the hands of the public.”

Nor did he retire from producing his own professional work to experiment with what he’d learned. Heck, he won his own Eisner Awards. In 1992, To the Heart of the Storm (Kitchen Sink) won Best New Graphic Album. His The Name of the Game (DC) won in the same category in 2002. And in 1997, his Graphic Storytelling (Poorhouse Press) won Best Comics-Related Book. In 2006, Eisner/Miller (Dark Horse) won for the same. Nor did his professional work decrease. At the time of his death at age 87, he was energetically in the midst of several more projects.

There’s More to the Story

The two openings to Bob Andelman’s Will Eisner: A Spirited Life (M Press, 2005 and TwoMorrows, 2015) provide examples of creators who came to Will’s work via reprints of his early tales. Michael Chabon wrote, “As a publisher, a packager, a talent scout, an impresario, and as an artist and writer, Will Eisner had created the world of comics as I knew it. But until I saw some of the later … reprints, I really had no idea who he was or what he had done.” Neal Adams wrote, “What I got from Will Eisner was a like mind. He was nothing like me, but in the areas of processing thought, moving forward, and taking a chance, we were absolutely like thinkers. If I were scratching around for an idea or I needed someone to bounce something off of, Will was the guy.”

Whether you were a fan, a student, a would-be pro, or a long-time creator, Will was the guy. Thanks to the vitality and health of the art form he helped to develop, we can continue to learn from what he left us.

No, what I’ve written is not enough. No brief essay can convey his brilliance, his variety, and his fundamental importance in the comic art field. Let me suggest, then, that you begin—or resume, depending on how well you already know him and his work—to explore the wealth of what Will Eisner did. You’ll learn a great deal. And you’ll have fun doing it.

Will Eisner’s birthday is this Friday, March 6 … celebrate it by reading a graphic novel or participating in a Will Eisner Week event near you. Comic-Con International and the CBLDF are hosting a panel discussion tomorrow night in New York City on the enduring influence of Eisner and The Spirit.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan.