MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 079: Beginnings

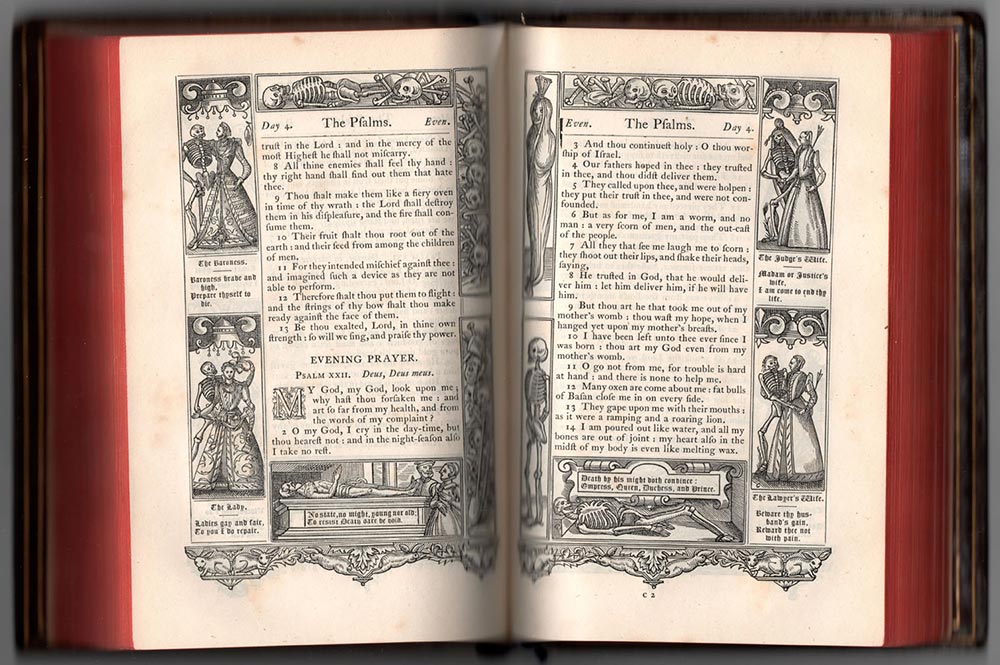

In a 2015 Heritage auction, I bought an Anglican prayer book for $56. The description was that it had “modern leather binding” and “all edges gilt.” I haven’t been able to learn much about it beyond that. The title page: The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments … Well, the title goes on for another 39 words. It says the edition is from London, R. and A. Suttaby, Amen Corner, 1863. And I haven’t been able to figure out much more about it—except to note that its letter “s” is the so-called “long s” that looks like an “f” and that the volume is an apparent attempt to duplicate an Elizabethan prayer book of three centuries earlier.

Among its many intriguing aspects, however, is the reason for its mention here: Whereas some pages are decorated with ornate designs, many are ornamented with what amount to comic strips of the life of Christ. Other panels provide reminders of the inevitability of death. Given the scarcity of information on the Internet, I’m guessing that such prayer books were (despite the title) an uncommon example of the presence of comics in past centuries.

Then …

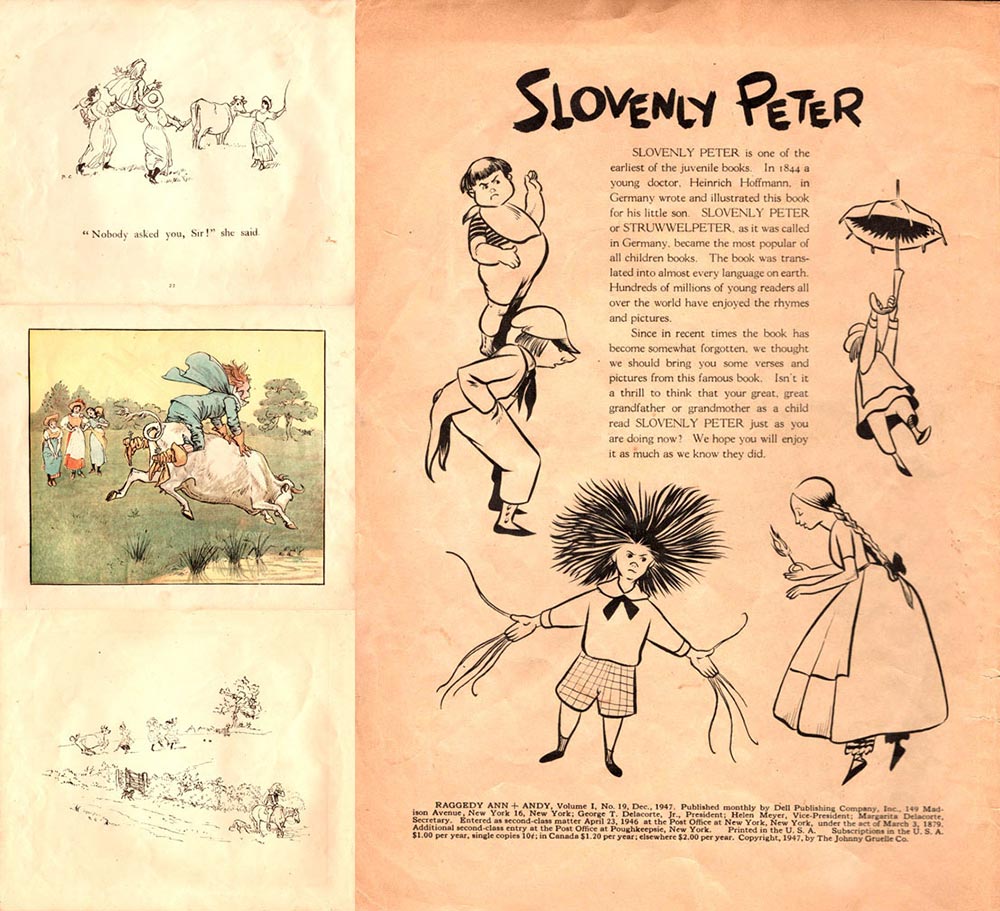

A couple of months ago at a collectibles mall, I bought a book simply because it fascinated me and was only $3. It continued to fascinate me, once I’d brought it home. There’s no date on the Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd. volume The Hey Diddle Diddle Picture Book “by R. Caldecott,” but a look at online listings tend to guess at 1890 or 1910.

Randolph Caldecott (1846-1886) was a British artist especially known for this sort of output. His work is so highly regarded that, in 1938, the American Library Association named its award for the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children the Randolph Caldecott Medal. (In 1922, the ALA had introduced The John Newbery Medal, named for a British bookseller, for “the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.”) My purchase contained Caldecott’s versions of the traditional rhymes “The Milkmaid,” “Hey Diddle Diddle,” “Baby Bunting,” “A Frog He Would a-Wooing Go,” and “The Fox Jumps over the Parson’s Gate.”

Since I’d taken a college course in children’s literature in the early 1960s, I’d been familiar with his work. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until I found and looked through this book that I realized that he’d basically been telling comic book stories: combining text, pictures, and panels to be read in sequence to tell more with the combination of words and pictures than were told by text or picture alone.

This is not the time to do a deep dive into the differences (if any) between picture books and comic books. The point here is that I’d never made that connection with regard to Caldecott before: He was a comic book creator before there were comic books.

And Then …

Many have heard of Caldecott, thanks to the medal, but fewer have heard of Heinrich Hoffman (1809-1894), though he was born before and lived after Caldecott. His Der Struwwelpeter was published in 1845, and I found out about it when I was 5, thanks to Dell Editor Oskar Lebeck, who had been born in Germany. Lebeck probably provided the translations of Hoffman’s work (with illustrations adapted by Dan Noonan) that appeared in Dell’s Raggedy Ann + Andy #19 (December 1947). Lebeck edited it and even provided the issue’s young readers (including me) an introduction concerning the poems that followed.

In other words, comics have existed in a variety of traditions via many different offerings. For example, the early 1900s, hardcover reprints of comic strips brought formerly discarded comic strips into homes in a durable format, thanks to such publishers as Saalfield and Cupples & Leon. A variety of magazine and other single-panel cartoons found their ways to homes, as well. Even libraries stocked volumes of cartoon from such magazines as Punch and The New Yorker.

Within the decade that followed that 1947 Dell comic book, Jules Feiffer brought a hardcover treasury of comic book reprints to readers.

Beginnings Need Not Be Actual Firsts

Clearly, that Book of Common Prayer, even if it had been a copy from the 1600s, wasn’t the first pop-culture comic art. David Kunzle’s The Early Comic Strip (University of California Press, 1973) was a hefty reference volume on antiquities of which some even preceded that prayer book. (It was subtitled Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825.)

On the other hand, there’s an ongoing continuation of turning points over the years. A look, for example, at The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide offers nice perspectives on comics starting in “The Pioneer Age” (defined as the 1500s to 1828) overlapping with “The Victorian Age” (defined as [pre-Victorian] 1646 to 1900). And so on.

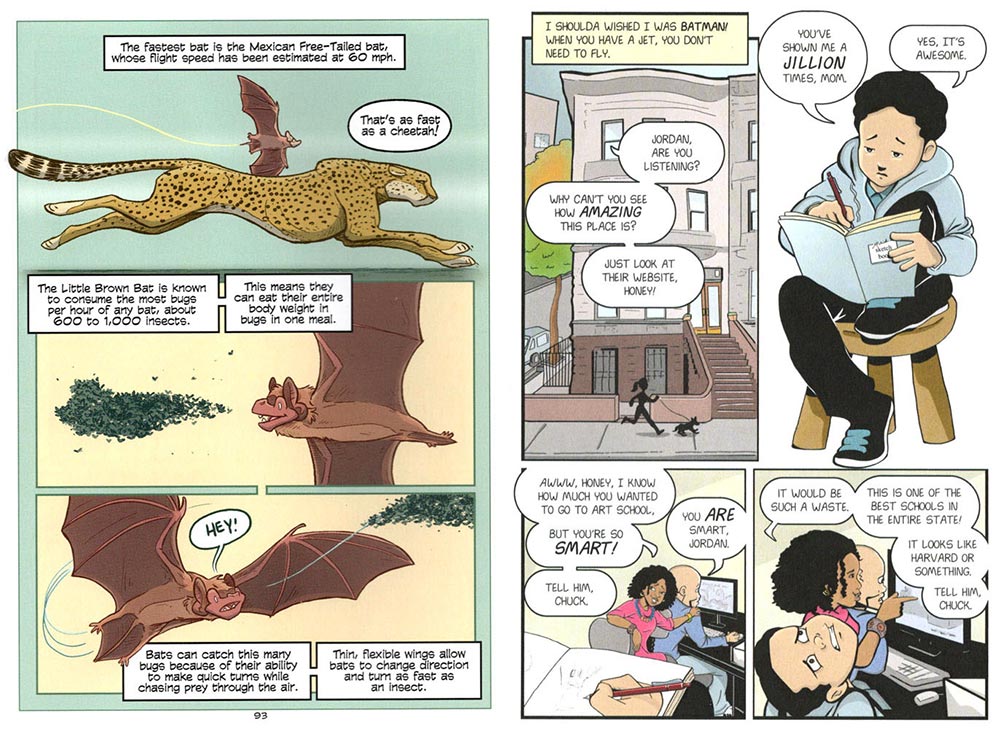

Looking back at our field can combine unlimited information with entertainment. And, by the way, education. Heck, using comic art as an educational medium had its own beginnings, too. Gilberton kicked off its Classic Comics in 1941 with its comic book version of The Three Musketeers. A decade later, Will Eisner began production of the how-to comic P.S. Magazine: The Preventive Maintenance Monthly for the Department of the Army. Eventually, it became almost routine to release educational material that used the clarifying art form of comic books.

So …

Two “beginnings” sparked this essay. The first was the discovery of that Caldecott collection at a collectibles mall. The second was the announcement January 27 this year that Jerry Craft’s New Kid had become the first graphic novel to win a Newbery Medal.

Consider: One of the earliest attacks on the very idea of comic books as appropriate reading matter for children came from Sterling North. His May 8, 1940, call to action claimed that comic books were “a national disgrace” and “a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years.” His own novel Rascal: A Memoir of a Better Era was one of the two Newbery Honor Books named by the ALA for 1964. But Rascal was an “Honor Book,” not the Medal-winner.

Eight decades after North’s attack, a comic book received the Newbery Medal.

It’s another beginning.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!