MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 067: Words

Polonius: “What do you read, my lord?”

Hamlet: “Words, words, words.”

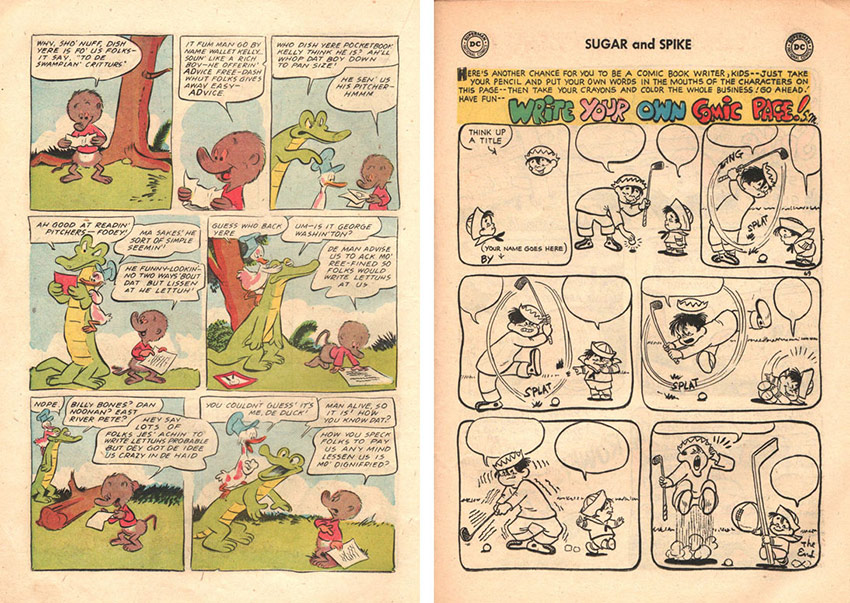

That was in Act 2, Scene 2; Shakespeare wrote those words around 1600, more than five centuries after the Bayeux “Tapestry” had told its story in pictures—and it came to mind while looking at earlier Maggie’s World columns, because it was in the very first installment that I quoted Albert the Alligator’s comment about words in Animal Comics #28: “Ah good at readin’ pitchers.”

It was certainly one of the appeals of comic books for the little kids that were attracted to picture-stories. But, given that, just how important are words in comic books? (Note that Walt Kelly used a lot of words on that page.)

Harvey Pekar remarked, in response to evaluations of comic art as somehow inferior to other art forms: There’s no limit to how good the pictures can be or how good the words can be. A major focus of many fans’ attention to and love for comics has been the pictures; fans quickly began trying to identify otherwise-anonymous storytelling by its art style. But far more anonymous have been the hundreds (thousands?) of comic-book and comic-strip writers.

Dell Comics editor Oskar Lebeck, himself a writer, often credited writers in bylines; many other Golden Age editors were not as forthcoming.

The process of providing to comics both stories and their words can, of course, be a complex endeavor. It can involve plots, layouts, rough pencils, and finished scripts. It can involve editors, writers, artists, other designers, and letterers. Writer-artists might find themselves with less editing, since they could be more in control of the package and, even if they worked anonymously (John Stanley, Carl Barks), they could sometimes do pretty much as they pleased. In other cases, writer and artist never even met.

Plus …

While we’re on the subject of the art of words, we can also consider the matter of putting words and sound effects on the page. Back in the ninth installment of this column, I discussed the origin of what Mort Walker popularized in Backstage at the Strips: Charlie Rice’s lexicon of symbols for expressions ranging from censored swearing to displays of emotion.

In fact, in lettering and layout, there’s the necessity of form following function: Most traditional comic book lettering is all uppercase. If the letterer doesn’t have to make extra room for ascenders and descenders, more words can fit in balloons and captions. But all-caps lettering makes reading more challenging for dyslexic readers, who often have to depend on word shapes for recognition.

Also customary has been the use of bold typeface, rather than italics or underlined words, for emphasis: Well, it just works, right?

Can you recognize distinctive lettering styles in comics? Todd Klein is an award-winning master of lettering that supports the story, indicates the speaker, and catches the eye. Walt Kelly, Dave Sim, and Chris Ware are among artists known additionally for their mastery of lettering as a function of their art. (Speaking of words suitable for framing, let me note that Klein’s Compendium of Calligraphic Knowledge is a print that is all words but gorgeously presented, with samples of kerning, line spacing, and balloon “air,” among other treats.)

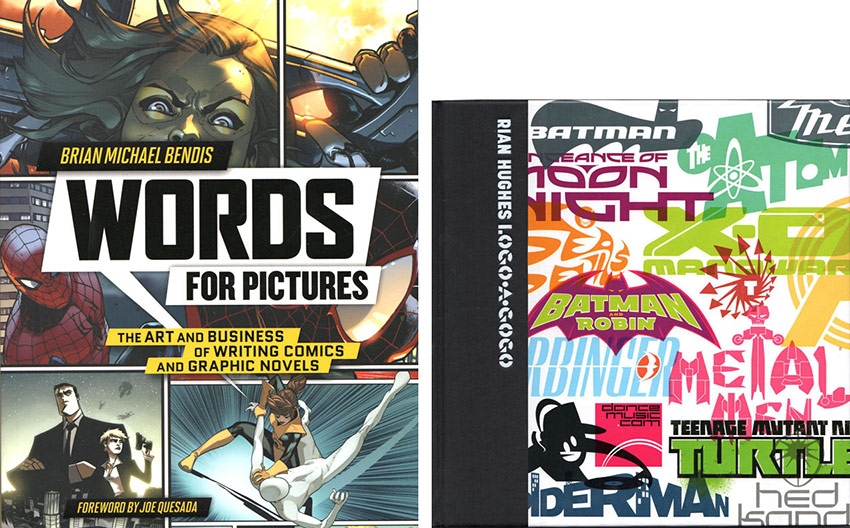

But that involves words in speech balloons and captions. What about words that identify something at a glance? What—in other words—about distinctive logos? When the words, themselves, are pictures?

One of the acknowledged geniuses of the art of the logo was Ira Schnapp (1894-1969), whose first such comics work was his redesign of the logo of DC’s Superman with #6 (September 1940). When you’re looking through the comics racks and back-issue bins, do the logos attract you? Do you look for certain designs?

Now

There are a plethora of books and other guides on writing comics and providing the words for the stories. Good writers and good artists have been there to help readers find the way for decades. If you have favorites, you might enjoy checking to see whether they have provided insights into their work. The more you know about the work that went into what wordsmiths have done, the more you’ll probably admire the skills that went into your entertainment.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!