Toucan Interviews

Cliff Chiang: It’s a Wonder-ful Life, Part 1

“WHEN BRIAN AND I FIRST TALKED ABOUT WONDER WOMAN, WE WERE COMMITTED TO IT FOR AT LEAST THREE YEARS.”

Cliff Chiang has been added to the select group of artists whose artwork has defined an iconic comics character. In Cliff’s case, it’s Wonder Woman, joining artists H. G. Peters, Ross Andru and Mike Esposito, George Pérez, Phil Jimenez, Adam Hughes, and Brian Bolland as the premier artists of the character’s almost 75-year run. His three years on the title, along with writer Brian Azzarello, redefined comics’ first great superheroine in the age of the New 52. In part 1 of our exclusive Toucan interview, conducted with the artist in early March, Cliff talks about how he got into comics—including the unlikely career path of starting out as an assistant editor—his influences, and much more. Cliff is the artist behind our official WonderCon Anaheim Program Book cover this year, and also a WCA special guest. (As always, click on the images in the article to see them bigger on your screen and in slideshow mode.)

Toucan: Where did comics start for you? What are your earliest comic memories?

Cliff: My earliest comics memories, like actually reading comics . . . I have vague memories of seeing comics around but I didn’t read them until my brother brought them home and I believe it was sometime around 1983, 1984. I remember the specific comics. There was a Fantastic Four comic and an X-Men comic and then after we read those we were off to the races. John Byrne was writing and drawing Fantastic Four. It was Chris Claremont and Paul Smith on X-Men, and it’s funny to think about that now, because those comics have really defined for me a lot of artistically how I handle comics and my storytelling. I didn’t realize it for quite a while, but then looking back and rereading those comics a couple years ago I realized that a lot of my storytelling choices come out of the clarity that you would get from a John Byrne comic, and a lot of my drawing comes from that kind of elegant drawing that Paul Smith would do. So those comics are really important to me for my development.

Toucan: When I was looking at your work in preparation for this interview, I looked over things like Wonder Woman, Greendale, and Doctor Thirteen, and I was surprised at how much your work reminds me of Paul Smith.

Cliff: Well, thank you. Yeah, I mean it’s kind of been on a pendulum sometimes. My work gets further away from it and then sometimes it kind of swings back to it, but I think he’s definitely a huge influence. And I think we probably also like a lot of the same artists as well, so that there’s just gravity to it that I can’t escape.

Toucan: Who else do you look at as major influences?

Cliff: Alex Toth, David Mazzucchelli, Steve Rude, the Hernandez Brothers. The Hernandez Brothers particularly I think in the last, well, when I started reading comics again after college. I had gotten back into comics in college and then after I graduated I realized I wanted to work in comics and kind of went on my own comics grad school course, just reading everything that had been recommended to me over the years that I heard was good. Finding Love and Rockets was an epiphany, just seeing these two guys, two men of color, making this fantastic book by their own rules and with these really great art styles. To this day it motivates me to do better work and to hopefully so something of my own that’s like Love and Rockets.

Toucan: So you definitely gravitate towards artists that have a clarity and a—not to make this sound like a bad word—simplicity to their work.

Cliff: Yeah, I like simplicity because it communicates quickly and easily without a lot of fuss. You know I think that the main goal of all this is storytelling. It’s not to sit back and “ooh” and “ah” at the picture. It’s to get the story across, and you know those artists and guys like Noel Sickles and Milt Caniff, Frank Robbins . . . there’s some Italian artists that I really love; Dino Battaglia in particular is a huge influence for me right now. Moebius . . . you know the one thing that they all have in common is they’re excellent storytellers.

Toucan: When you were reading comics as a kid did you realize at one point in time that somebody wrote and drew these and this is what you wanted to do as a career?

Cliff: I knew really well that there were people doing this. As soon as I started reading comics as I kid, I think you know it’s like getting into sports or something and learning who’s on each team and that kind of thing. So I knew who all the individual names were. I knew that, oh, I like this person’s art and this person’s writing, but I never considered it as a job. It was kind of abstract for me. I knew these things were made, I knew someone had to draw them, but I never thought that it could be a job for me and it took a long time before I could kind of accept that. I didn’t know what I wanted to do as a kid at all, but artist was not necessarily at the top of that list, even though I was drawing a lot.

Toucan: But eventually you went to Harvard and started there in filmmaking, right?

Cliff: Yes, and I think that’s what started me on a path back to comics, because I wanted to tell stories. Film seemed to be—at that time—the most interesting to me, but after doing a bit more film and learning about cameras and having to collaborate with actors and writers and just a whole team, I realized how big a production a film actually is, and I wanted more control over the storytelling. I could tell stories on my own without worrying about cameras screwing up on me, without worrying about film going bad, and it was just a much smaller, simpler process.

Toucan: So basically you realized at one point you could make your own movies on paper.

Cliff: Yeah, pretty much.

Toucan: You started in comics as an assistant editor at Disney Adventures magazine and then at Vertigo. Was that a conscious decision on your part to enter comics that way instead of just starting out with submitting samples and going the art route?

Cliff: I knew I wanted to draw, but I also knew that my work wasn’t professional. Knowing that I wanted to be in comics in some capacity, I tried to get any job I could, and editorial was difficult to get into because there weren’t many spots, but it seemed like a natural fit. So I sought out editorial jobs at first because I felt like I would learn things by doing that that I wouldn’t learn otherwise, and at the same time I could continue to work on my art until it was something that someone could publish.

Toucan: That must have been an incredible learning experience for you to see all this art as it came in every day and see how different artists tell stories.

Cliff: Yes. It started with Disney where we—Heidi MacDonald and I—worked with a lot of veteran artists who knew what they were doing, so I very quickly got a sense of how to do things, what good storytelling was. She also had these great cheat sheets that were made by a Disney artist at some point about how to compose pages for comics. How you’d want to leave space for balloons, how you’d want to move the action, and how you’d want to play with perspective to keep it interesting. Through that I learned what real clarity in storytelling was. We also worked with Jeff Smith reprinting Bone in Disney Adventures magazine. So I got to talk with him a little bit and we saw copies of his full-size pages come into the office and I could stare at those for hours. After that, at Vertigo, one of the jobs of the assistant editor is to kind of log in some of the artwork that comes every day from the different pencilers and letterers and inkers. So I’d see that and compare it with the script and see how things changed or how the penciler would interpret the script. So each day was a different variation on that and I learned a lot there as well.

Toucan: So was there a moment when you felt, okay I’m ready to start to do this after looking at everybody else’s work?

Cliff: No, there wasn’t. There was a feeling that I wanted to do it and I started to get smaller jobs internally at DC while I was working there. I did a couple of the “Big Book” series because a friend of mine was editing them, but you know, there’s feeling like you’re ready and then actually being ready, and it was difficult for me to get bigger jobs because I was on staff. I had a 9 to 5 job, which meant that I’d have to go home and work at night in order to get anything done, which meant that I needed a much longer lead time than you would give any other full-time freelance artist. Occasionally offers would come in or someone would say, “Oh, we thought of you, but then we went with this guy,” and I appreciate that they even told me, but after a few of those I started saying well, maybe I should think about this. Then, as it happened, they rearranged the department and I took that as a sign that I could go, because I was being moved to a different editor and the time that was going to be spent getting used to their books and their creative teams meant that it was going to be another six months before I was really comfortable, so why not take this an opportunity to leave and just double down on the idea of making comics.

Toucan: Your first ongoing work was the Josie Mac series in Detective Comics.

Cliff: Yeah, that’s right.

Toucan: At that point did you feel you’d kind of made it, since you got a little bit of an ongoing gig?

Cliff: I’m trying to think back. Yeah, I did. Even though it was an eight-page backup, it was in Detective Comics, the comic that the company was named after, and it was doing a character that luckily was created by Judd Winick and myself and we had Batman in it. So it felt like everything I’d ever asked for all in one package. The character we had some control over and then we were getting Batman to guest star in it, so it kind of felt like a gift. There was part of me that felt like I was ready for it. You know there’s always that little bit of arrogance I think that you need, honestly, as an artist to even do anything. You have to feel like what you have to say is worth saying and that part said, oh, yeah, all right, we’re on our way, but the rest of me was kind of shocked by it.

Toucan: What was it like the first time you collaborated with a writer? Was that a shock to you? Had you been doing your own comics before, writing your own stuff before you actually got the Josie Mac gig, or were you just doing sample pages?

Cliff: I was doing minicomics and sample pages and before Josie Mac I think there were maybe like one or two small things. One was a double-page spread for Transmetropolitan that Warren Ellis wrote that I loved, and then I also did a four-page short story in the Flinch anthology that John Rosen wrote. And I would say even after, even during Josie Mac, I didn’t talk with Judd all that much. It wasn’t until later on Beware the Creeper that I was really collaborating from page one with the writer and that was Jason Hall. We talked all the time about the scripts. Then once I got them, occasionally I would change some things here and there and it was a great collaborative process and kind of exhausting, too, because we were both so hungry for it at the time and kind of going over everything with a fine tooth comb.

Toucan: That was kind of a watershed moment for you because not only do you get to have your own book, but you got to revamp a classic character in the Vertigo mode and I think you went in a direction that nobody expected.

Cliff: Yeah it was open country. They kind of left us to do whatever we thought would be cool with it and that kind of freedom is really great, especially when your editor backs you up on it. It’s really nice to know that you have that kind of latitude to do things that feel right and not be constrained by something like continuity or just previous publishing history of any sort. So we could just kind of go with it and go where the story needed to go. Visually it was fun to kind of put a stamp on everything and come up with that world. So it was a great feeling and it’s kind of one that I enjoy feeling. You don’t get it on every job, but I try to recapture it wherever I can.

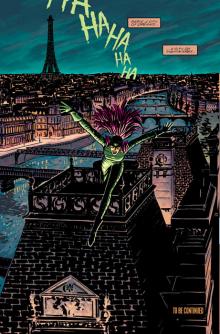

Toucan: How did you guys decide to (A) make the character female, and (B) set it in 1920s Paris?

Cliff: I think the female thing came first. We thought that that would be the first way to distinguish a different Creeper. I know that they had done revamps of the Creeper already in the DCU and nothing really stuck and frankly ours didn’t either but it was a nice little kind of anomaly. We had planned for it to be a story of an artist fighting against the authorities, and as such it started to have a kind of dystopian feel and it—as we were coming up with the pitch—started to veer pretty closely to V for Vendetta, which doesn’t need to be redone. So the editor, Will Dennis, asked if we had thought about going to the near future. The near future is all well and good, but it’s kind of the go-to for any of these kinds of stories. So, what if you went back historically to a time that would fit and he suggested 1920s Paris, partially I think because Moulin Rouge had come out that year. And it seemed to fit the personality of the Creeper and we were skeptical at first, but after doing our own research we realized how perfect it was and told Will, yeah, this is great. That’s exactly what it needed and it really made the book different, it made it unique because of that historical aspect to it.

Toucan: Your work seems to be marked with a number of books that have strong female characters. Is that by choice or just it kind of happened? You have the Creeper, Black Canary in Green Arrow and Black Canary, obviously Wonder Woman, and the protagonist in Greendale is a woman. Is that by choice?

Cliff: I would say it’s not necessarily by design, but somehow over the years I became known for drawing women, which I never would have guessed [would happen], especially when I was like 13 or 14 trying to draw superheroes and the women always turned out horribly. But it was something that just kind of happened at some point. I think maybe the Creeper was part of that or it started with Josie Mac, just drawing Josie in a certain way and then taking it from there to the Creeper. It’s just developed over the years and it’s great. I think you end up working on different kinds of stories than if you’re just drawing the hard-jawed, blonde hair, blue-eyed superhero all the time.

Toucan: That’s kind of my next question. Your work seems to be pretty evenly split between superhero projects and nonsuperhero ones. Do you have a preference?

Cliff: I like to bounce between the two whenever I can. I feel like I can get stuck in a certain way of thinking and seeing and drawing things and the best way for me to break out of it is by doing different material. Greendale was so rooted in everyday reality, which was a lot of fun to research and a lot of fun to draw and try and bring to life, but after that I wanted a little bit of a break from that, so I did some superhero stuff. But it wasn’t until doing something like DMZ where there was absolutely no fantasy to it at all, it was just this kind of bombed-out version of New York City and that allowed me to try to approach my art more as illustration and to think about how you’re drawing things. One of the things that I’ve learned over the years is that when you’re drawing normal everyday stuff, it actually helps to have a more heavily stylized art style, because you’re just drawing a cup or a chair and so you want to be able to throw more of your personality into that drawing versus if you’re just trying to draw a superhero and make it believable then you might lean towards just making it as naturalistic as possible. So doing DMZ allowed me to kind of open up a little bit more stylistically, and I’ve been trying to follow that path ever since.

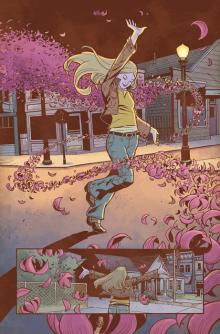

Toucan: Going back to Neil Young’s Greendale, that must have been a major commitment for you. What was it, 144 pages or something as a graphic novel?

Cliff: Yeah I think we ended up at 168 pages, and yeah it was a commitment. I didn’t know it was going to be that long when I first heard about the project, I just knew it was going to be a graphic novel, and when I did sign on I just received this brick of a script. It was really long. It was a lot of material to get through, and it took me a while to read it a couple times and really digest it. Even throughout the drawing of it I would call the writer, Josh Dysart, and talk things over, because I’d have problems with certain scenes or I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to draw them and so we’d talk it through and usually by the end of the conversation we’d have a great answer or solution to whatever problem I had with it. I think getting all that material at once was daunting, and the hard part about drawing it is you kind of have to keep all that material in your head as you’re drawing it. Something you draw on page 1 might call back to something on page 150 because of the nature of graphic novel versus just 20 pages a month coming out monthly.

© 2010 Neil Young Family Trust and DC Comics

Toucan: The thing I found unusual about looking at it again, is there is no black in the book. I mean obviously you inked it and everything, but the way it’s colored it’s like a deep brown or a deep purple for all the black.

Cliff: Yes.

Toucan: Was that a conscious decision on your part, or was that colorist Dave Stewart’s decision?

Cliff: I had wanted to do the coloring. Ideally I wanted it to look like my cover work, which would show some spot blacks, but black as a color and everything else would be knocked back into a different color. Sort of like Disney’s Sleeping Beauty movie. That was a big influence for me color wise and I wanted it to have that feel, but I realized how much work that is for an artist and I thought well, if we scaled that back and just removed the black and printed it in this rich brown, it would give the feel of the book being older, as if Greendale wasn’t a brand new book. Almost like you were looking at an album of family photos. I wanted that warmth to it, that kind of worn-in quality. That’s something that you get from Neil Young’s music, I think this kind of lived-in experience. So I talked to Dave about what if we just knock this all back and then you adjust your pallet to work with it and he thought it was a pretty cool idea. And then he went further and added some coffee stains on pages and really kind of roughed it up and it really made it feel so homey.

Toucan: And very organic, too, which certainly fits in with the story.

Cliff: Yes, that was the other thing. I was afraid that for a story like that, my art, especially the way I was drawing Greendale, could be a little too slick and too clean and the result is that looks kind of flat and graphic. I wanted to warm it up somehow whatever way possible.

Toucan: What attracts you to any project that you’re offered?

Cliff: It needs to have some heart. I was talking to Eduardo Risso once and he was complaining about a script. His English is great, but he’s not a native English speaker and one of the things he said was “it has no argument,” which I thought was great. It’s a great way to put it. Any work that you do needs to be postulating something. It needs to be trying to show something new or something different and trying to communicate with the reader. So what I look for and when I’m most happiest is when the story has some heart to it.

TM & © DC Comics

Toucan: So with Wonder Woman and the relaunch of the New 52 you were working with Brian Azzarello again, who you did Doctor Thirteen with. Are there writers that you’ve worked with before that make you want to sign on again?

Cliff: Yeah, it’s great to work with people that you’ve worked with before. You have a shorthand and you know what to expect from them and you can build on your prior experience. I’d love to work with Brian Vaughan again. We did a Swamp Thing really early in both our careers and we’ve been trying to get together to do something, but there are other people who I would love to work with too, that maybe I worked with editorially, Garth Ennis or Warren Ellis. I would love to work with them as well. So I have a long list of people, and the great thing about comics these days is that there are so many people to choose from. There’s so much good work out there.

Toucan: Any urge to write your own stuff?

Cliff: Yeah I’ve done writing more. I did an eight-page story in Batman Black and White #6 and it was . . . I always knew that I’d be writing my own material at some point. I’m not sure how much of it will be written by me or by other people, but it’s something that I want to do more of and now that I’ve started it’s kind of this boulder that’s rolling downhill, so hopefully I’ll be able to write something soon, because I have too many ideas rolling around in my head.

Toucan: It’s kind of unusual for a team these days in comics to stick on a book this long. I’m guessing you’re going on three years at this point on Wonder Woman, if you figure in the start time for when DC launched the New 52. What’s kept you interested all this time?

Cliff: We started with a very specific story and we’re actually just getting to the end of it now in this third year. So we knew that was our job, to do these three years’ worth of stories. We never wavered throughout that. I think at some point after the first year, someone said to me, you know, you could go and do something else now if you want, and that was never an option because when Brian and I first talked about Wonder Woman, we talked for a few hours and came up with the bare bones of what we’re doing right now and as a result, we were committed to it for at least three years. We could have jumped off at any point but we wouldn’t have finished our story.

Toucan: What attracted you to Wonder Woman besides working again with Brian? Here’s an iconic character that’s been around for going on 75 years, again it’s a strong female character that some people would argue hasn’t quite been given her due in a lot of arenas, including comics and movies and TV. Was it Brian’s story that hooked you? Was it the fact that you got to draw this iconic character?

Cliff: I would say it’s everything that you just mentioned. Working with Brian again was certainly a priority for me. Wonder Woman seemed like a great fit for me and maybe perhaps less so for Brian, which is what made it really intriguing. And the fact that there was this huge publishing history for Wonder Woman and all these different versions and the status of the character . . . frankly it was intimidating, and that’s what drew me to it, it was a challenge. What new twist could we come up with for Wonder Woman to make her story compelling? It scared me a bit, but sometimes you need that to really push you to work hard. There have been a few projects like that, that did kind of scare me a little bit. Creeper was one of them, too.

In Part 2 of our Toucan interview with WonderCon Anaheim 2014 special guest Cliff Chiang, he talks about his thoughts on cover design, more Wonder Woman, his move toward more digital art, and much more! Click here to read Part 2! And click here to buy badges for WonderCon Anaheim 2014 and get your own copy of the official Program Book with Cliff’s wonderful Wonder Woman cover!