MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 024: Tricky Business

“I re-used old story plot formulas—not stories in the full sense. I thought I was revising the locale and characters enough to look fresh to the new generation of readers. Neither I nor the editors guessed that readers of the first versions were still buying comics.” That’s what Uncle Scrooge creator Carl Barks told Malcolm Willits in the course of the “Duck Man” interview Don and I printed in Comic Art #7 in 1968.

Part of the art of producing comic books on a demanding schedule is using one or more of the tricks of the trade to make the most efficient use of the time involved. Sometimes, even such talented writer-artists as Carl may divide the work with other collaborators. He commented on the challenges such processes could involve, when his editor would send him story concepts from other writers: “They didn’t write stuff that was easy to stage, and so I took the liberty of rehashing their stuff quite a bit. Some of the stories I changed so completely that, after two years went by, I thought I wrote the whole thing.” But he added that he sometimes did get good material from other sources. “Now that story where Gladstone and Donald were up in the Bering Sea and they found that old Viking boat—that story came to me from Dana Coty, who used to be an editor on Judge magazine years ago.” Carl bought the idea from him and developed it for Dell Four Color #408 (July 1952), “The Golden Helmet.”

It’s a plot!

Making comic art is a tricky enough business that its creators have had to resort to a number of devices to keep it coming on time all the time. OK, admittedly, when he was looking for story ideas, even Shakespeare often began by resorting to Holinshed’s Chronicles or other plays. (Hello, King Leir!) Heck, Homer saved plotting time by turning Greek tradition into verse, right? But we’re talking comics here, so focus!

The earliest editors began providing quick comic book content by patching comic strips together until an issue’s pages were filled. Hey, they were looking for what was cheap, fast, and plentiful! Famous Funnies (“famous” because the contents had already been in wide newspaper circulation) introduced the concept of a monthly dime comics treat with #1, dated July 1934. Its pages were packed with reprints of The Bungle Family, Tailspin Tommy, Mutt and Jeff, Dixie Dugan, and many more such strips.

As competition increased and newsstands gradually filled with an ever-increasing variety of four-color delights, new stories began to catch readers’ attention. That meant a search for added material—and for new and different stories.

But sometimes editors could come up with ways to make new material from old sources.

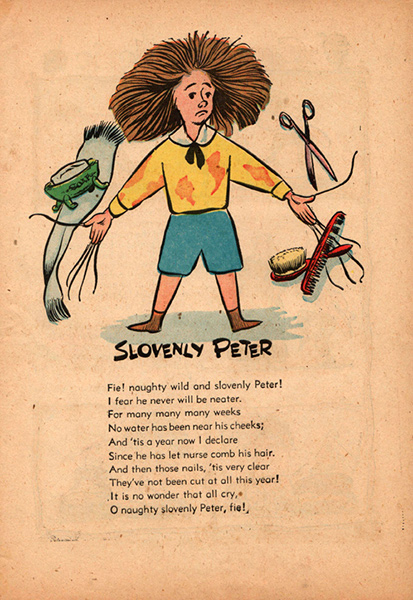

In Raggedy Ann + Andy #19 (December 1947), edited by (German-born) Oskar Lebeck, the introduction to eight pages of illustrated poems read, “Slovenly Peter is one of the earliest of the juvenile books. In 1844 a young doctor, Heinrich Hoffman, in Germany wrote and illustrated this book for his little son. Slovenly Peter or Struwwelpeter, as it was called in Germany, became the most popular of all children [sic] books. The book was translated into almost every language on earth. Hundreds of millions of young readers all over the world have enjoyed the rhymes and pictures. Since in recent times the book has become somewhat forgotten, we thought we should bring you some verses and pictures from this famous book. Isn’t it a thrill to think that your great, great grandfather or grandmother as a child read Slovenly Peter just as you are doing now? We hope you will enjoy it as much as we know they did.”

Hah! That’s eight pages filled—with the bonus of a ninth for the introduction! (Moreover, it was the first time I’d ever seen Hoffman’s work, albeit translated and re-illustrated. So maybe Lebeck was right.)

Some gag cartoonists—such as the New Yorker’s Helen Hokinson (1893-1949)—simply provided illustrations for which a gag source provided the humor. In her posthumous The Ladies, God Bless ’em, published in 1950, gag-writer James Reid Parker wrote an introduction including an obituary that included the information, “In 1931 a chance meeting with James Reid Parker led to a professional association that lasted for the next eighteen years, with Mr. Parker devising the situations and writing the captions for most of Miss Hokinson’s drawings.” She hadn’t kept it a secret; she’d even dedicated When Were You Built? (1948), “To James Reid Parker whose captions have inspired most of these drawings.” In his extended introduction to the 1950 collection, Parker discussed the circumstances in which Hokinson had arranged to have him provide what amounted to the plots for her illustrations. He provided a detailed view into such collaborative work.

But consider the tricks of writing. Authors are often asked, “Where do you get your ideas?” It can be a challenge, and one of the solutions can be as simple as swiping. Famously, when the E.C. line published a story based on the work of Ray Bradbury, he reminded the company that he was owed a royalty check. The response produced a profitable relationship.

Heck, Gilberton’s entire line of Classics Illustrated comics were based on the premise that public domain tales could be used for perpetual recycling of profitable adaptations.

The Art

Speaking of swiping, using someone else’s plots isn’t the only way to speed up comics production. Artist Howard Boughner showed Don and me some of his swipe files in the 1960s—including actual chunks of original art, cut out for reference because of their potential usefulness. I think he mentioned that Sears catalogs were another helpful resource and I bet he wasn’t alone in that regard.

Mind you, using reference materials could come in different ways. Dell republished many comic-strip compilations—including Floyd Gottfredson’s “Phantom Blot” story from the 1939 Mickey Mouse comic strip, scripted by Merrill De Maris. For some reason, though, when Dell used the strips later as back-up serials in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, Dell didn’t just reprint what it had already (re)published. Artist Bill Wright told us that, when he had adapted Gottfredson material, he had been required to change every single panel. And, clearly, Dick Moores was told the same. For evidence, readers can compare the recently reprinted Gottfredson “Phantom Blot” story with the six Comics and Stories serial episodes in #101-#106 (February-July 1949). The script is the same; each Moores panel is different from Gottfredson’s art.

Story-generating tricks can go beyond something that simple. Marvel’s Stan Lee, of course, not only came up with “The Marvel Method” (story conference with writer and artist, artist drawing the story, then scripting based on conference and art). Stan and his artists also pulled some of the same tricks DC’s Julius Schwartz had already initiated in updating and revamping characters from an earlier era. (After all, The Fantastic Four were a combination of Plastic Man, The Human Torch, Invisible Scarlet O’Neil, and, well, a generic Marvel monster, right?) The faster the story-creation process, the greater the possible output.

Coming Attractions

Other media continue to look for what is cheap, fast, and plentiful. Eight decades have passed since Famous Funnies acquired tales from comic strips, and such comic books as The Lone Ranger, Tarzan, and Bugs Bunny have since told many new tales of existing characters from radio, TV, and movies.

Then, things turned around a bit. In its search for popular tales to tell, Hollywood (for example) has discovered more than one success in comics. The process has become almost traditional. Whether in movies or on TV, versions of Spider-Man, Batman, Superman, and Captain America seem to be in constant reiteration. It’s almost a cyclical marketing device. Comics provide plots and characters for movies and TV, which provide material to be licensed for toys, statues, and clothing. And books. And ideas for fan fiction. And, eventually, a new generation of creators. The little girl wearing a Wonder Woman outfit today may write or draw her own revamp of the character in a decade or so.

You know, once other media producers expand their search engines and licensing departments to rummage through old comics, we could see feature films, webcomics, books, and videos of … Well, who knows? Square eggs [Donald Duck Four-Color #223]? Airboy fighting rat armies? [Airboy Comics #58]? Magnus, Robot Fighter [in either his Dell or Valiant incarnation]? Possibilities are endless.

All of which suddenly makes me realize that there might be a fresh wave of investment to come. After all, if Marvel Super-Heroes #18 (introducing The Guardians of the Galaxy) can go from 25 cents in 1969 to a price-guide value of $60 a decade ago to more than $10,000 in 2014 … What do you think may happen to the back-issue price for Sunfire & Big Hero Six #1 (Sept. 1998)?

No. Forget that. We like comics because we like comics. What’s of far more basic importance than collector prices is that great stories be kept in print to influence writers and artists in the generations to come. I think it was Harvey Pekar who said, “There’s no limit to how good the art can be, and there’s no limit to how good the writing can be.” We have delightful entertainment in our future, whatever tricks its creators may use to bring it to us.

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!