JESSE HAMM’S CAROUSEL

Carousel 007: “Meanwhile, back on the ranch…”

When you’re in the midst of drawing a scene in a comic, it’s often easy to imagine the next image in the sequence. The script says, “He cooks breakfast,” so you draw him cooking breakfast. Next it says, “He eats breakfast,” so you draw him eating breakfast. Simple. The tricky part comes when you must switch to a new location, or a different time-frame. “He later visits the zoo.” What image will best communicate that he’s left his kitchen and is now at the zoo?

A common default would be to show a big external shot of the zoo. However, you don’t always have enough time or space for such a thing. Also, seeing the same approach used for every scene transition can become tiresome for readers. Don’t let yourself be trapped by that default. You may decide after all that a big external shot would be best, but surveying your other options first can ensure you make the wisest choice.

To that end, here are ten ways to show readers that the story has jumped to a new time or location. We call these “scene transitions,” or “transition panels.”

1. Caption.

(Art credit: Jean Giraud, Blueberry: Arizona Love.)*

A caption is the easiest way to move the story to a new time or location. It can tell you unequivocally that a new scene has begun, how much time has passed, and where you are now. In this panel (image #1), I’d like to imagine the caption says, “Meanwhile, back at the ranch…” A classic of the western genre! (Alas, it’s actually describing the town.)

Unfortunately, captions aren’t always an option. Sometimes a caption may seem intrusive or corny, or may hamper the story’s pace. This leads us to our second option…

2. Establishing shot; no caption, no characters.

(Art credit: Alfonso Font: Le Labyrinthe Du Dragon.)*

Here we have the “zoo” option I mentioned earlier. You show (not tell!) the new location, often with a speech balloon emerging from the part of the environment where the characters are located. The absence of characters piques the readers’ curiosity, inviting them to seek out the characters in the next panel.

This is perhaps the most common form of scene transition. Elegant and comprehensive.

3. Establishing shot with featured character.

(Art credit: Alfonso Font: Le Labyrinthe Du Dragon.)*

In this case, we switch things up a bit by including the featured character visibly in the panel. This is a good option when there’s no dialogue but you want to add some personality to the scene. Or, when there IS dialogue, but you want to identify the speakers right away.

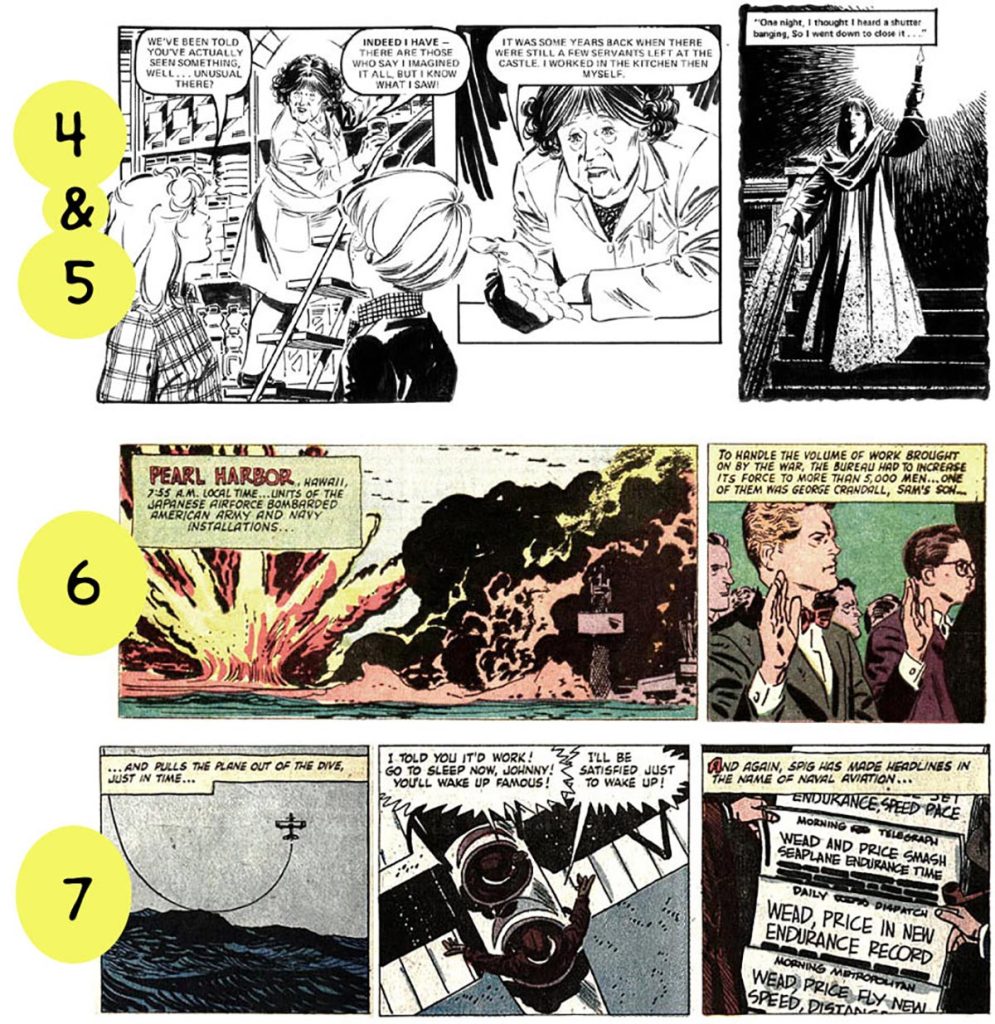

4. Character changes clothing or appearance.

(Art credit: Santiago Hernandez, “The Protector,” Girl #99.)*

In this scene, the lady introduces a flashback. The shift in time and location is helped by her dialogue, but we can also see this shift by the changes in her appearance: her robe and longer hair. No environmental details are needed; her appearance alone tell us the new panel has transported us to an earlier point in her life.

5. New lighting: light to dark, or dark to light.

Another approach (illustrated here by the same sequence of panels) is to change the lighting from day to night, or vice versa. If the lighting shifts dramatically, readers will realize right away that the new panel occurs at a different time in the story, even if no other changes have been made.

6. Incongruous action.

(Art credit: Alex Toth, “The F.B.I. Story,” Four Color Comics #1069.)*

Here are two panels from Alex Toth’s The F.B.I Story. In the first panel, Pearl Harbor is being bombed. But in the other panel, several men are standing at attention, being sworn-in during a ceremony. Even without reading the captions, and without any background detail, we can see that the men occupy a different time and place than the bombing. After all, they wouldn’t be so calm if bombs were dropping on their heads!

The incongruity of actions A and B here remove the need for a cumbersome establishing shot of whatever locale the men happen to occupy.

7. Incongruous foreground element.

(Art credit: Alex Toth, “The Wings Of Eagles,” Four Color Comics #790.)*

This transition works on a principle similar to the last, but this time it’s an object rather than an action that reveals the transition. We don’t need to see the background or environment in the final panel to know that we’ve moved to a new locale, for the simple reason that biplanes don’t contain racks of newspapers.

8. Characters with new prop.

(Art credit: Alex Toth, “The Lennon Sisters Life Story,” Four Color Comics #951.)*

Here’s a little trick you can do with props. The action in this case has moved from the bedroom to the bathroom. To indicate the bathroom, we could include an incongruous foreground element (as in section 7), such as a sink or toilet … but that would be clumsy here, since the characters are conversing and we want to see their faces. The solution? A toothbrush and toothpaste! No one brushes their teeth in bed, so these props will suffice to show that the men have left the bedroom.

9. Same pose, new background.

(Art credit: Alex Toth, “Sugarfoot in Eye Witness,” Four Color Comics #907.)*

This is a weird one that only works in comics. If you show a character in the same pose in successive panels, even slight changes in the background will indicate that he has moved to a new location. In this example, for instance, the disappearance of the fence in the second panel suggests that the man has crept forward.

The key here is that the character must be shown in the same pose, from the same direction. If there are changes in either his pose or his position relative to the reader, the reader may assume the character has simply changed his posture, or that we’re viewing the character from a new vantage point, or that the background was drawn inconsistently by accident. By keeping the character’s pose and our relation to him the same, you emphasize that the changes we see in the background actually represent a new location.

10. Establishing shot, stretched over different panels.

(Art credit: Mike Mignola, “The Baba Yaga,” Hellboy: The Chained Coffin and Others.)*

Here’s another one that only works in comics.

In this example, Mignola has drawn an establishing shot much like the one we saw earlier, in section 2. But he’s broken it up in an interesting way by including an inset panel at the upper right, and dividing the establishing shot into two panels: panels 1 and 3. The result is that you get the same information that you would have gotten had the establishing shot been a single panel, but you get different parts of that information at different times. It’s as though Mignola has split a paragraph into two paragraphs and inserted another paragraph in between them. The establishing shot therefore precedes and follows the second panel, lingering longer in our attention than it would have had it been contained in a single panel. Probably not an approach you’ll need often, but a great example of how limber comics can be when called upon.

There you have it: ten ways to convey changes in time or locale. The next time you make a scene transition, ask yourself which of these approaches might be most suitable. Or perhaps invent another!

See you here next month!

*All images copyright respective copyright holders.

Jesse Hamm’s Carousel appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!