MAGGIE’S WORLD BY MAGGIE THOMPSON

Maggie’s World 052: Abstracted

Harvey Pekar pointed out that in comics, there’s no limit to how good the words can be or how good the pictures can be.

But what if the pictures are … well … short of masterpiece status?

Years ago, I discussed with Joe Orlando the challenges of providing thumbnails with comic book layouts, and he suggested I do what he’d recommended to others wrestling with the problem. “When you’re doing rough layouts, just draw a star to indicate the character,” he said. “That way, you don’t get bogged down in trying to figure out how the thumb connects to the palm.”

While that’s OK for rough layouts, I used to be more demanding when it came to the finished art for a comic book or comic strip story. I found myself limiting my admiration to comics artists whose work was based on correct anatomical structure—or on consistent adaptation to a stylized cartoon anatomy. (I’ve always appreciated such controlled stylizations as John Stanley’s for Little Lulu, Frank Jupo’s comic book fantasies, and Charles Schulz’s carefully structured two-dimensional creations.)

But what I used to consider “sloppy” comic art … Well … I dismissed it.

Eventually, though, I began to realize that powerful match-ups of words and pictures don’t necessarily require meticulous artistic realism.

Decades ago, for example, I’d enjoyed the work of Munro Leaf. (There’s more about him and his comic art in the 10th installment of this series. Click here to read it.) In his series for Ladies’ Home Journal, the kids who were observed with disapproval by his “Watchbirds” were basically stick figures. Characters in his …Can Be Fun books were similarly primitive.

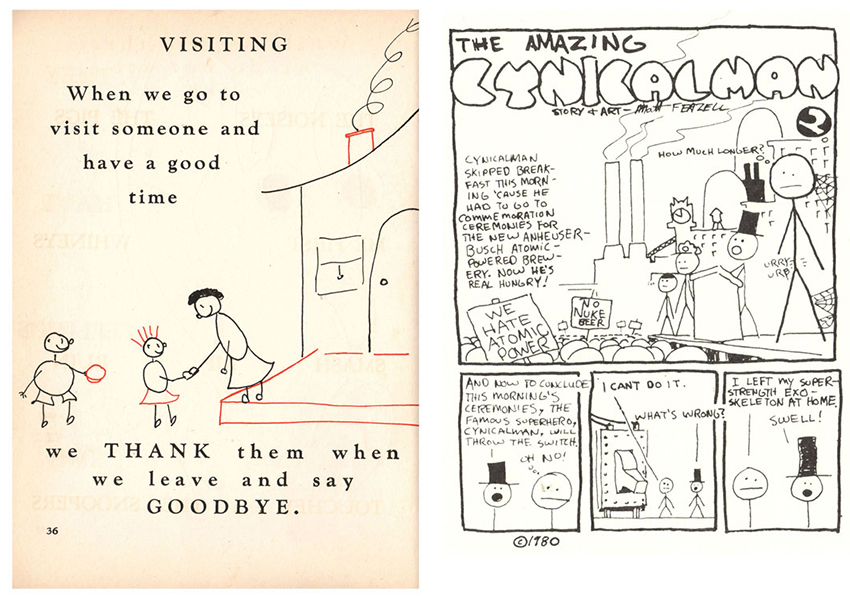

Despite that, he crafted a career with his line drawings—and today there are several successful skilled creators who use such images to provide illuminations for their tales. The Cynicalman work by Matt Feazell and the webcomic xkcd by Randall Munroe demonstrate that such an approach can work well.

Nor is non-representational comic art limited to stick figures.

Goofy Graphics

As comics fandom emerged, its denizens were informed by three basic reference books: Martin Sheridan’s Comics and Their Creators (1942), Coulton Waugh’s The Comics (1947), and Stephen Becker’s Comic Art in America (1959).

The primary focus of the three was the comic art found in newspapers. Sheridan pretty much limited his mention of comic books to an entry on Superman; Waugh and Becker limited themselves to a chapter each on the comic book business. Waugh’s comic-book complaints included the comment that “it doesn’t seem possible that anything so raw, so purely ugly, should be so important.” Becker, writing later, was more kind—though he indicated that it was primarily a mere stepping-stone to a better kind of comic art: “The industry employs thousands of men, and has proved a good starting point for aspiring cartoonists.”

But each expressed admiration for the oddball zany art in features they singled out as classic. In a wrap-up chapter of Comic Art in America (1959), Becker wrote about “The Lyric Clowns,” which he listed as George Herriman, Crockett Johnson, Walt Kelly, Charles Schulz, Milt Gross, and Rube Goldberg. Gross’ Yiddish wordplay may be responsible for his smaller audience these days—despite his pioneering wordless comics novel She Done Him Wrong. Nevertheless, Waugh wrote, “There is something archaic about him; he is the funny man who has had a good time and laughed since man’s dawn-days.” Becker commented that both Calvin Coolidge and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. had paid tribute to Gross, devoting many pages to a man he called “one of the century’s great comic artists.”

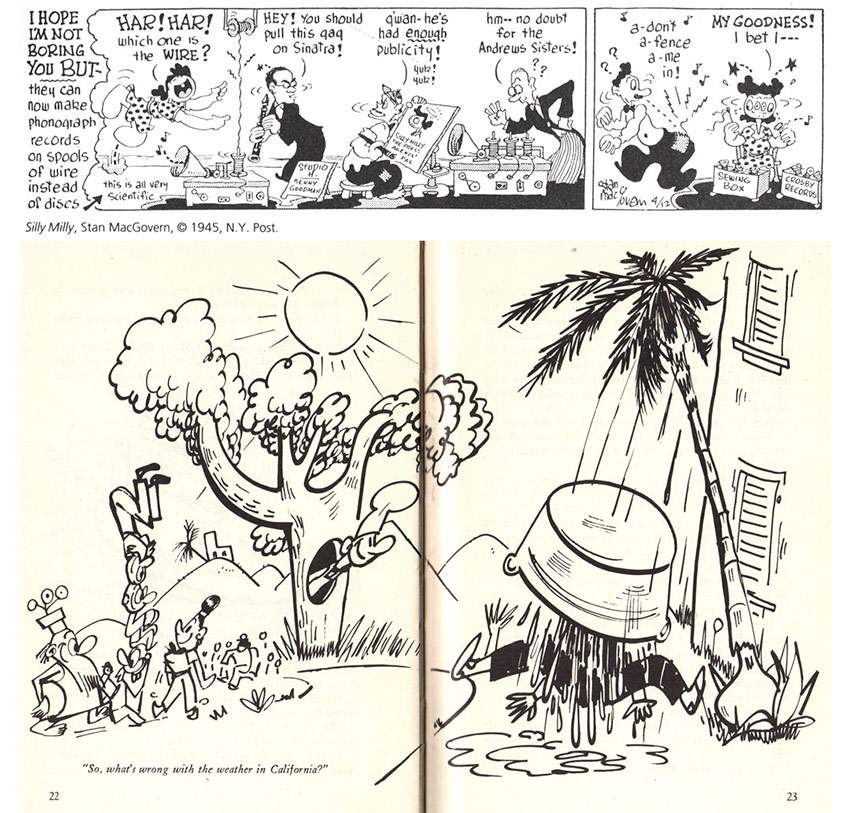

Less well known—almost never reprinted—was a cartoonist to whom Becker tipped his hat in his last paragraph, referring to Stan MacGovern, “whose Silly Milly wowed readers consistently for as long as he drew it.” Ever heard of it? It’s hard to find a sample these days, though the feature began in 1938 and ran into the 1950s. The strip shown here comes from Ron Goulart’s reliable 1990 volume The Encyclopedia of American Comics, where he provided more information than there’s room for here. The strip’s influence spread, though its fame has dwindled over the years. Jack Mendelsohn’s Jackys Diary strip (originally without an apostrophe), for example, clearly reflected MacGovern’s influence.

And Today …

Clearly, decades of dedication to powerful images of superheroes and amusing depictions of anthropomorphic funny animals haven’t restricted reception of less representational art in storytelling.

In her stunning 2013 book collection of Hyperbole and a Half, for example, Allie Brosh conveyed, as the cover said, “Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened.” Though her imagery bordered on the abstract, it made her messages clear and their impact immediate.

She told National Public Radio’s Terry Gross in 2013, “The reason I draw myself this way is that I feel that this absurd squiggly thing is actually a much more accurate representation of myself than I am. … I am this crude absurd little thing, this squiggly little thing on the inside. So it’s more of a raw representation of what it feels like to be me.” She added, “Really, a lot of time goes into this crudeness.”

And more and more examples of the excellence of non-representational art in comics continue to appear. The work of such brilliant creators as Matt Groening, Marc Hempel, Lynda Barry, Jason Shiga, Daryl Seitchik—and, for that matter, to such concepts as “rage comics”—provide a mosaic of abstraction.

So much for my early preconceptions of what “good art” might be.

In fact, what it boils down to is this: There’s no limit to how good the words can be or how inventive the pictures can be.

Lucky for us!

Maggie’s World by Maggie Thompson appears the first Tuesday of every month here on Toucan! All of our regular featured writers will be taking off the month of July.