STEVE LIEBER’S DILETTANTE

Dilettante 026: The Importance of Sketchbooks

Telling stories with comics requires that an artist keep things consistent. Characters, settings and props generally need to look the same from panel to panel, page to page, story to story. And a cartoonist—even one who draws “realistically”—needs to create a stylized, abstracted world that maintains a consistent feel. If you’re distorting color or perspective or anatomy, you want to do it in a way that feels the same from one panel to the next, or you risk pulling the reader out of the story. Similarly, you’ll usually want to keep your graphic approach in the same key throughout the story. If you’re drawing the first 4 chapters with a thin, inflexible outline and no surface modeling, it’s going to feel very strange if you switch to bold, swoopy brush lines and dense lattices of crosshatching halfway through chapter five. And if you start a story about heroically proportioned figures in lushly modeled color, readers will be disoriented when you switch to austere, natural proportions with limited touches of flat tinting.

So unless you have a good storytelling reason to shift gears, you want to keep your art consistent. But it’s easy for that consistency to turn to stagnation. Artists thrive on experimentation and readers crave novelty! And what had been a welcome stability can quickly turn into a dreary repeat performance. “Seen it. What else you got?”

You’re going to need a way to keep your energy up, your eye sharp and your imagery fresh. You need to keep a sketchbook.

Now don’t be intimidated by the published sketchbooks you see at conventions, full of finished works that are every bit as polished as the cover of a hardcover graphic novel. Most of those are mislabeled. They’re portfolios and artbooks. Your sketchbook isn’t for show. It’s not for the public to see how awesome you are. It’s a place to think, to observe, to learn, and to fail and fail and fail.

You can try different media to see what they’ll teach you. As an art student, I was terrible at drawing with brush & ink, the traditional tools for the kind of comics I wanted to make. I just couldn’t figure out how to move from the ambiguous grey murmur of my pencil art to the clear, graphic declaration of a page drawn boldly in ink. My ink drawing sucked, and it was killing me. But a few years later, brush and ink became my favorite tools. What got me there? Sketching from life with a hard charcoal pencil. Charcoal felt a lot like graphite, but the line was a deep, dense black and it was almost un-erasable. The charcoal line was close enough to an ink-line that I started to figure out the graphic rules that make ink drawings work.

Later, charcoal became my medium for more detailed studies. As my work in comics became increasingly graphic and linear, my sketchbooks became the place where I’d spend hours trying to precisely capture light and texture. (Click on the images below to see them larger on your screen and in slideshow mode.)

Sketching was also important for me in learning to understand how to create a sense of weight and movement. That isn’t something you learn from careful observation of light on form, but rather from watching people move. I always love sketching dancers at clubs. It’s never easy to capture the gestures of dancers. They aren’t exactly holding still for you to make a careful study. But if you pay close attention, you’ll notice interesting lines, shapes and patterns. (Important: Please don’t creep people out by staring at them for a long time. You’re trying to get better at drawing, not make strangers feel uncomfortable.)

Aaron McConnell (The Gettysburg Address: A Graphic Adaptation, 13th Age)

I started life drawing again this year after doing very little over the past couple years. I came to the realization that it feels very different from working in the studio on comics or illustrations, and it doesn’t really drain my energy the way I feared it would. I can usually get back in the studio after a 3-hour session. I prefer drawing on 18″ x 24″ newsprint at an easel, so I can stand up (I call it exercise) and work at arm’s length. It’s hard to say if it helps me get more done when I’m back in the studio, but the practice of observational drawing is definitely beneficial in a muscle memory sort of way, and it seems to improve my drawing from reference and imagination. I plan to keep at it with the hope that I’ll be able to see improvement by the end of the year, but either way they’re just scribbles on newsprint, so who cares? As a commercial artist my desire to refine or heaven forbid “get precious” with my work seems to continually increase, so it’s also beneficial having an outlet where I can draw and not be overly concerned with the final outcome.

Jesse Hamm (Hawkeye, Good as Lily)

I sketch for the usual reasons but I REFUSE to carry around a sketchbook to sketch randos in public. Artists are always advised to sketch anyone, anywhere, but I think that’s bunk. Non-models move too often for you to sketch them completely, so you end up supplying the missing information from memory, wearing deeper grooves in whatever flawed ideas you have about how people look, and defeating the whole purpose of observational drawing.

Lucy Bellwood (Baggywrinkles, Cartozia Tales)

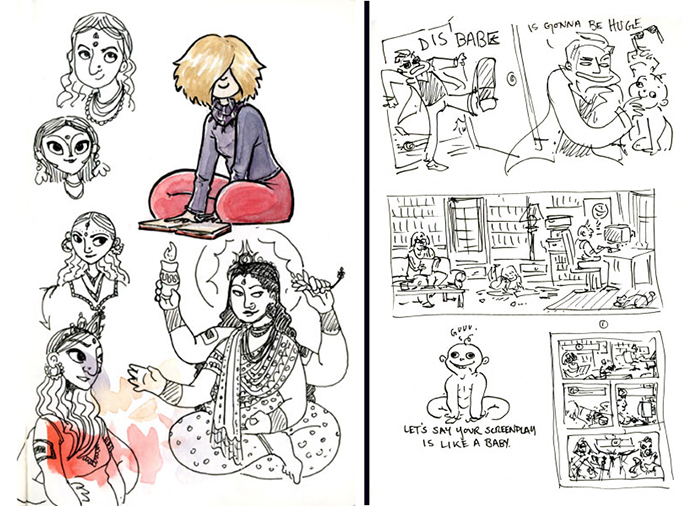

My sketchbook is my most valuable staging ground for ideas and process work. I use it for developing character designs, snooping on people on buses, in coffee shops, and anywhere else they’ll stand still long enough for me draw them, and sorting out scripts and thumbnails for projects.

These days I try to do most of my sketchbook work directly in pen. It stops me getting precious about the lines I make. In an ideal world my sketchbook is a place where I’m allowed to be imperfect and messy in the pursuit of nailing down a gesture or an expression or an idea. Being able to think on paper is one of a cartoonist’s most valuable tools. It keeps my lines fresh and my brain thinking in terms of replicating the world around me in the most efficient way possible.

I’ve become really partial to drawing Hand•Book sketchbooks―they take watercolor beautifully, the pages are smooth enough to ink on, and they’re durable enough that I took one down the Grand Canyon for three weeks and it lived to tell the tale. I usually work in the 5.5 x 8.5″ size―sometimes even drawing whole comics straight in the book, but optimally I want to be plowing through a couple pages of rough work a day.

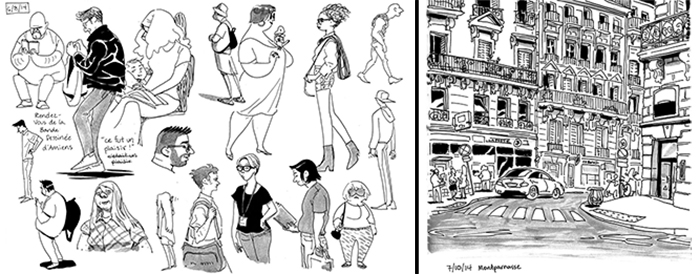

Natalie Nourigat (Between Gears, Thrilling Adventure Hour OGN)

My favorite sketching exercise is going to a coffee shop with windows facing a busy street, and surreptitiously drawing the people outside for an hour or two. I don’t go for realism so much as capturing the personalities of different people, and exaggerating the things about them that stand out to me (giant purse, crazy hair, interesting posture/proportions/gesture, whatever) to make quick character sketches. People don’t tend to stand still in the wild, so it’s a good exercise for my memory, as well as a reminder to draw what’s important to get an idea across and not be too precious about it. When I go back to drawing comics, it helps me draw more diverse and interesting characters.

My favorite sketching tools are the Platinum Carbon Pen (line art), Pentel Pocket Brush Pen (heavy shadows), and a Pentel Aquash Waterbrush Pen filled with a watered-down ink (gray washes).

Do you keep a sketchbook? Any favorite artists I should follow to see what they do in theirs? Let me know! I’m @steve_lieber on Twitter and on Facebook I’m at facebook.com/steve.lieber

Steve Lieber’s Dilettane appears the second Tuesday of every month here on Toucan!